Exhibition

At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World

Want to know more?

Past

September 7—November 2, 2024

Opening Reception

Saturday, September 7, 6–8 PM

Location

Los Angeles

606 N Western Avenue

90004 Los Angeles CA

Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat: 10 AM-6 PM

Artist

Curators

Hilton Als

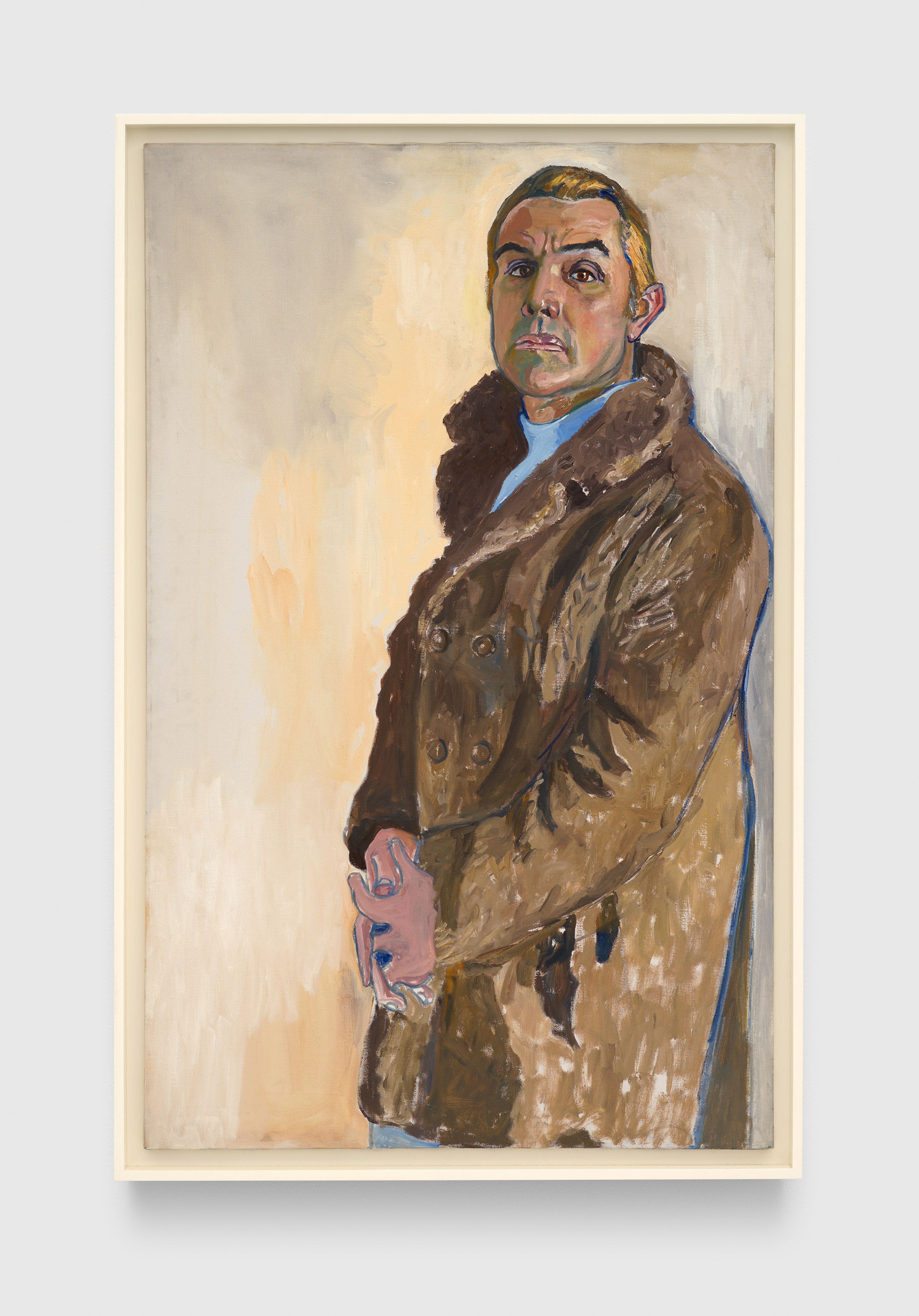

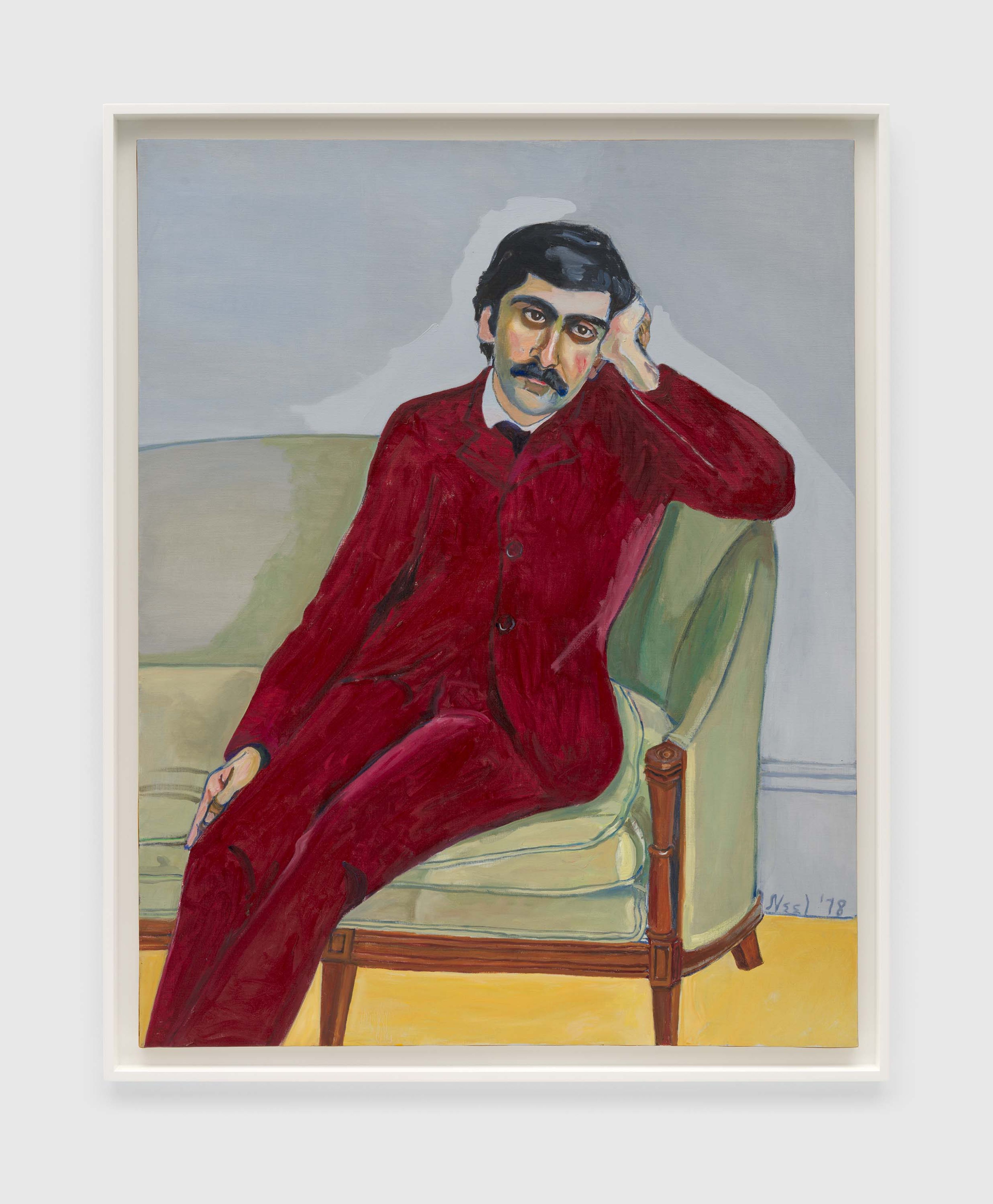

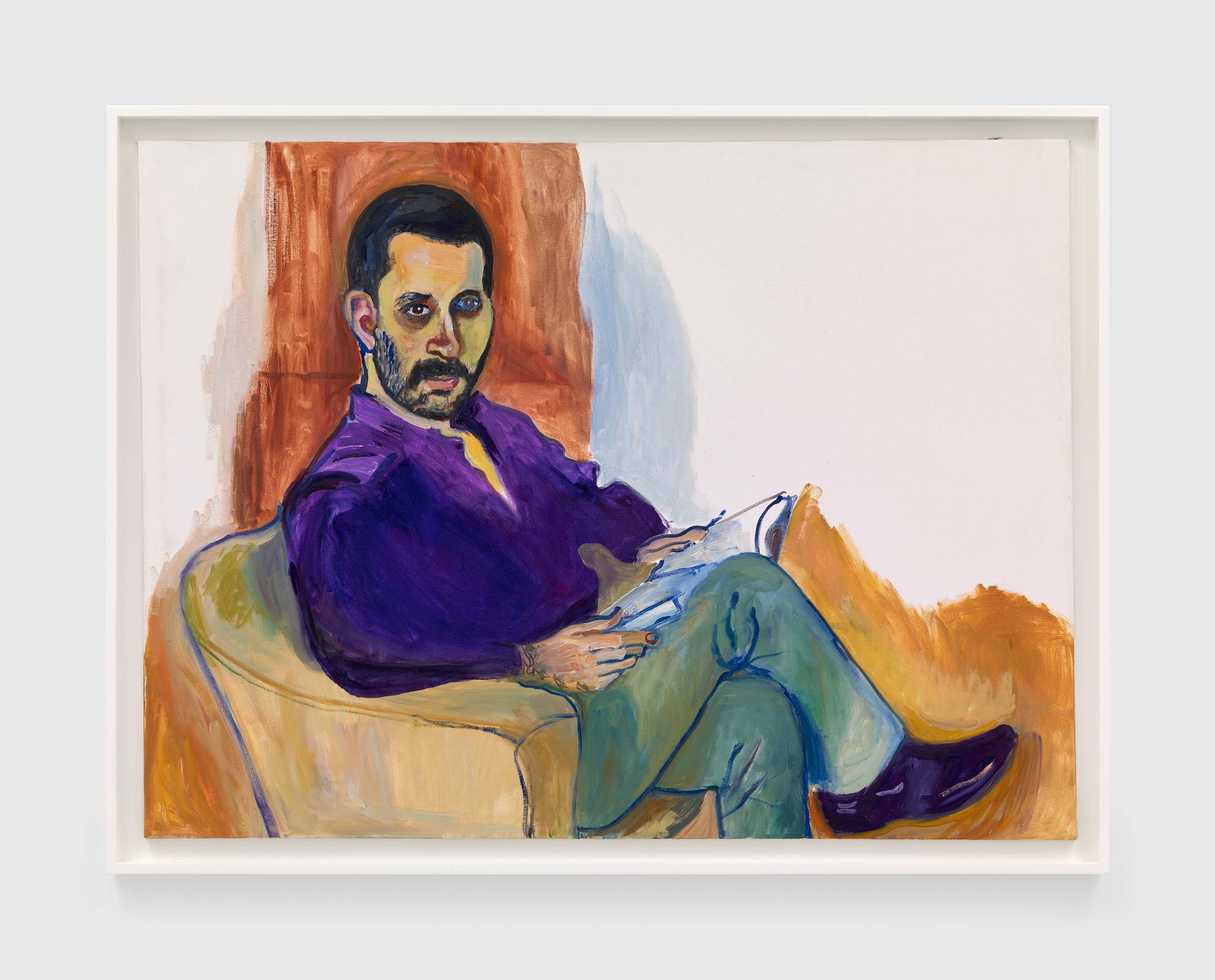

Alice Neel, Dennis Florio, 1978 (detail)

Explore

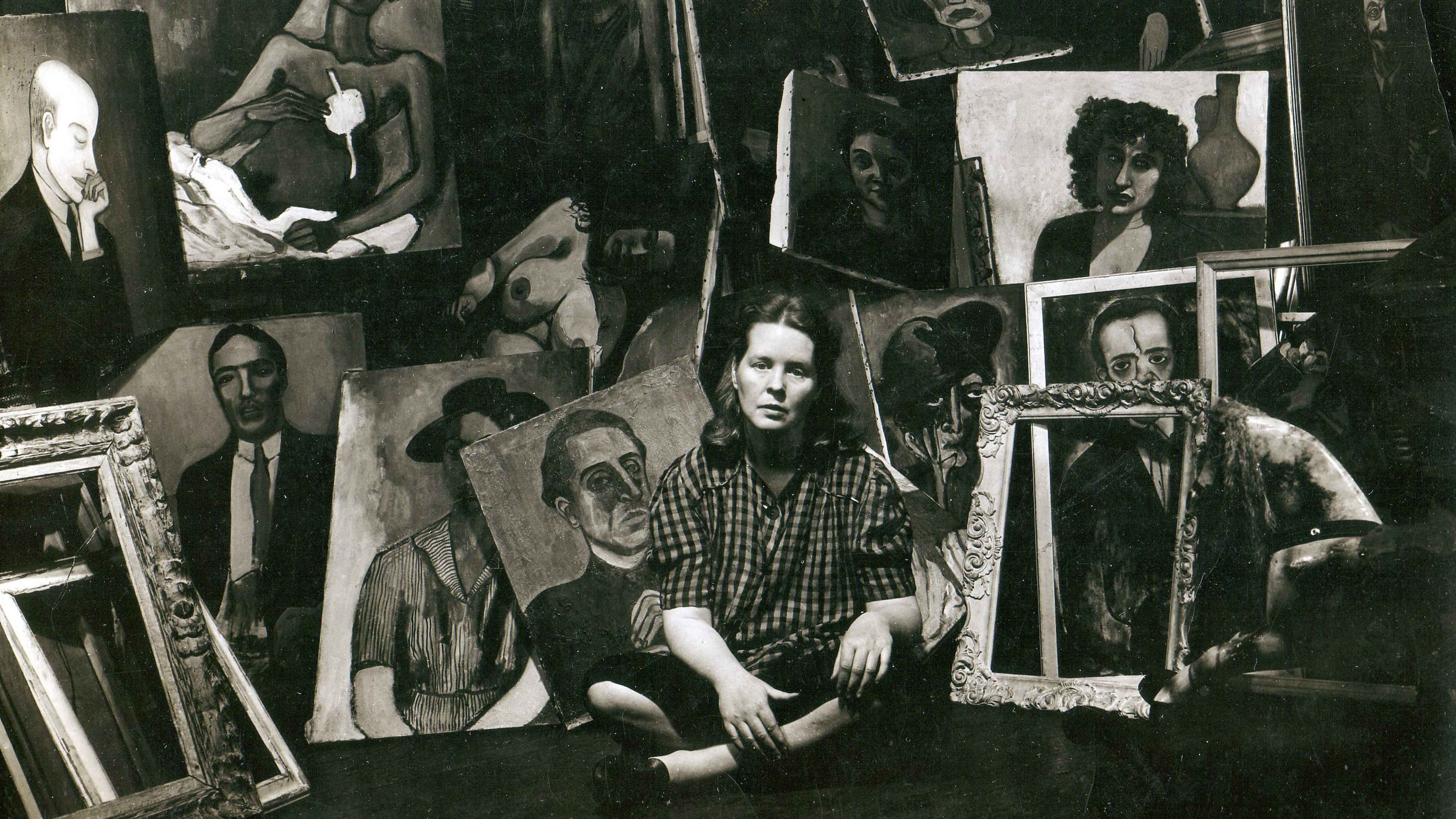

Alice Neel with her paintings at her Spanish Harlem apartment, 1944. Photo by Sam Brody

“When she died in 1984, Neel had a great number of masterpieces to her credit, a galaxy of masterpieces, I would say, that bear witness to the terror we usually turn away from, having no language for it, namely alienation, disconnect, love.”

—Hilton Als in his catalogue essay in At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World

Installation view, At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World, David Zwirner, Los Angeles, 2024

Alice Neel with Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky on the set of Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie’s Pull My Daisy, 1959. Artwork © John Cohen Trust, courtesy L. Parker Stephenson Photographs, New York

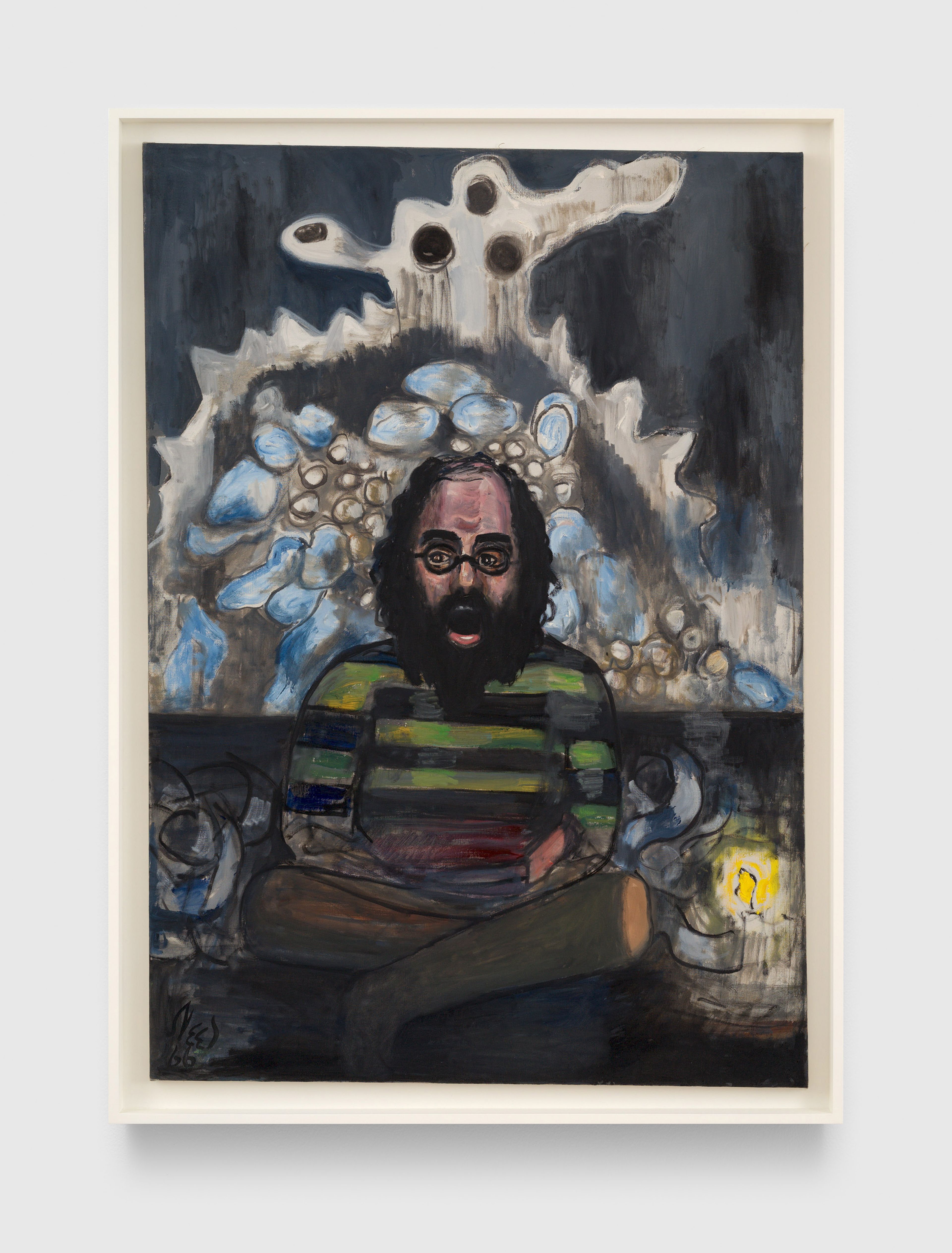

Among the works on view is a depiction of American writer and poet Allen Ginsberg. While a student at Columbia University in New York, Ginsberg met William S. Burroughs, Lucien Carr, and Jack Kerouac, joining a group of writers that would later become known as the Beat Generation. In his work, Ginsberg wrote openly about his identity and gay desire, challenging the obscenity laws of the time and paving the way for younger LGBTQ+ artists and writers to express themselves freely.

Allen Ginsberg, second from left, joins psychologist Dr. Timothy Leary on stage for the multimedia presentation "Illumination of the Buddha," The Village Gate, New York, December 6, 1966. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah. MUUS Collection via Getty Images

“I looked like a conventional American type. I had a hat then, and orange gloves and an orange scarf. I went (to the first day of shooting) and there was Allen Ginsberg. So I said, ‘Oh, are you taking the part of Allen Ginsberg?’ And he said, ‘No I am Allen Ginsberg.’”

— Alice Neel on her experience filming Pull My Daisy with Allen Ginsberg in 1959

Alice Neel, Allen Ginsberg, 1966 (detail)

Alice Neel, Frank O'Hara, No. 2, 1960 (detail)

Installation view, Alice Neel: Every Person Is a New Universe, Munch Museum, Oslo, 2023

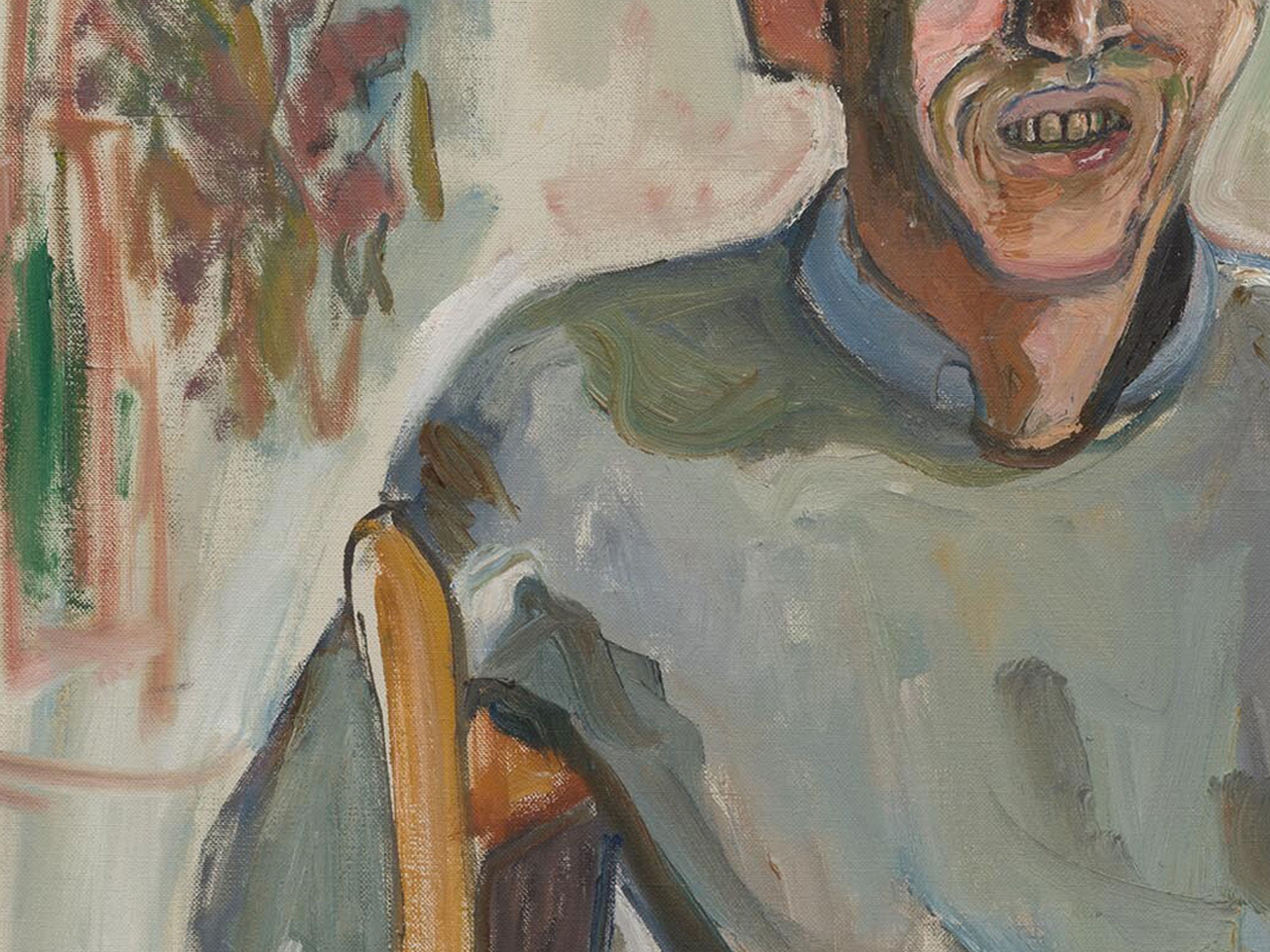

“Frank O'Hara, No. 2, showing O'Hara smiling through teeth that the painter later compared to ‘tombstones,’ is one of Neel's masterpieces, and one of the great works of American figurative painting.”

— J. S. Marcus, The Wall Street Journal, 2008

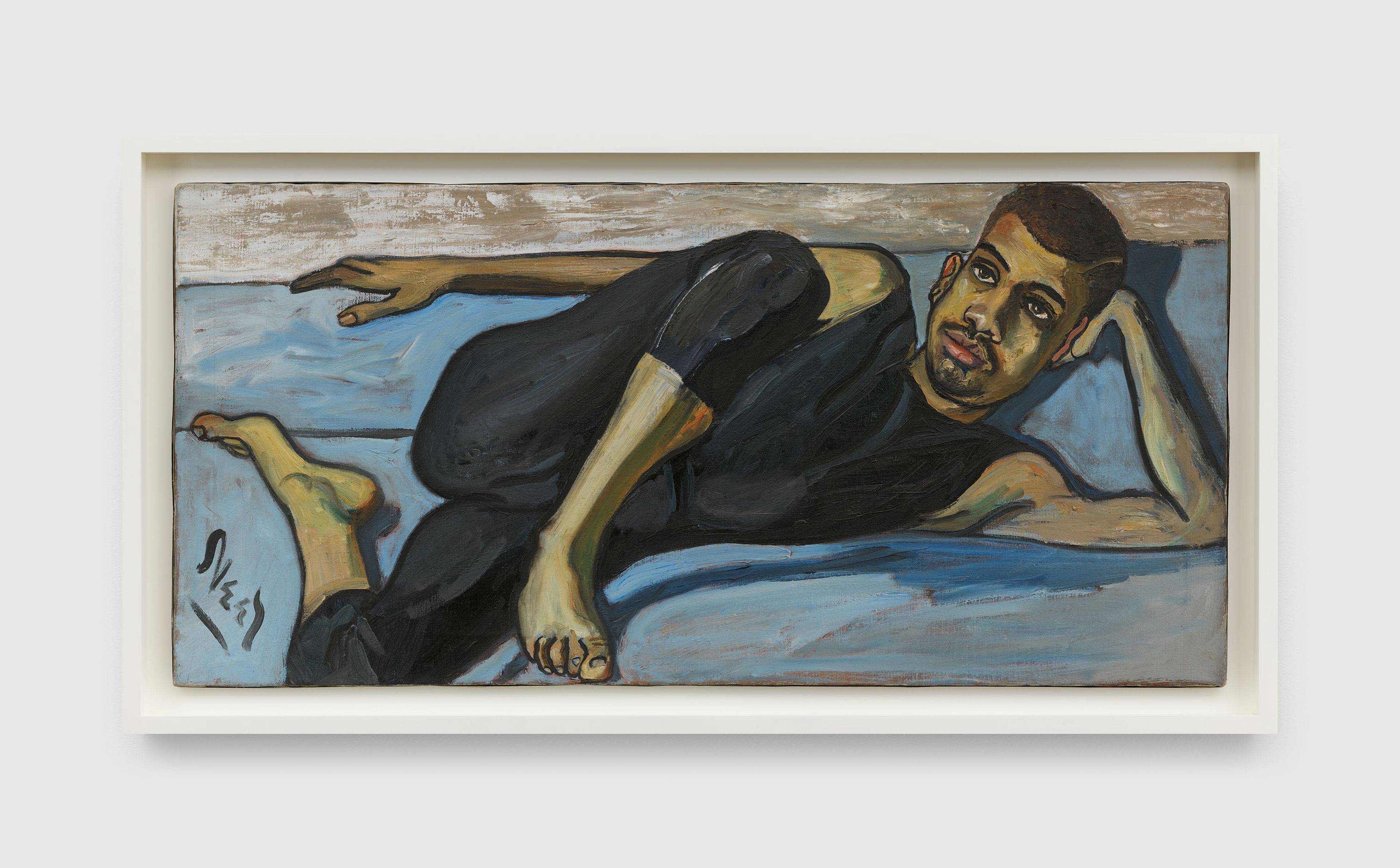

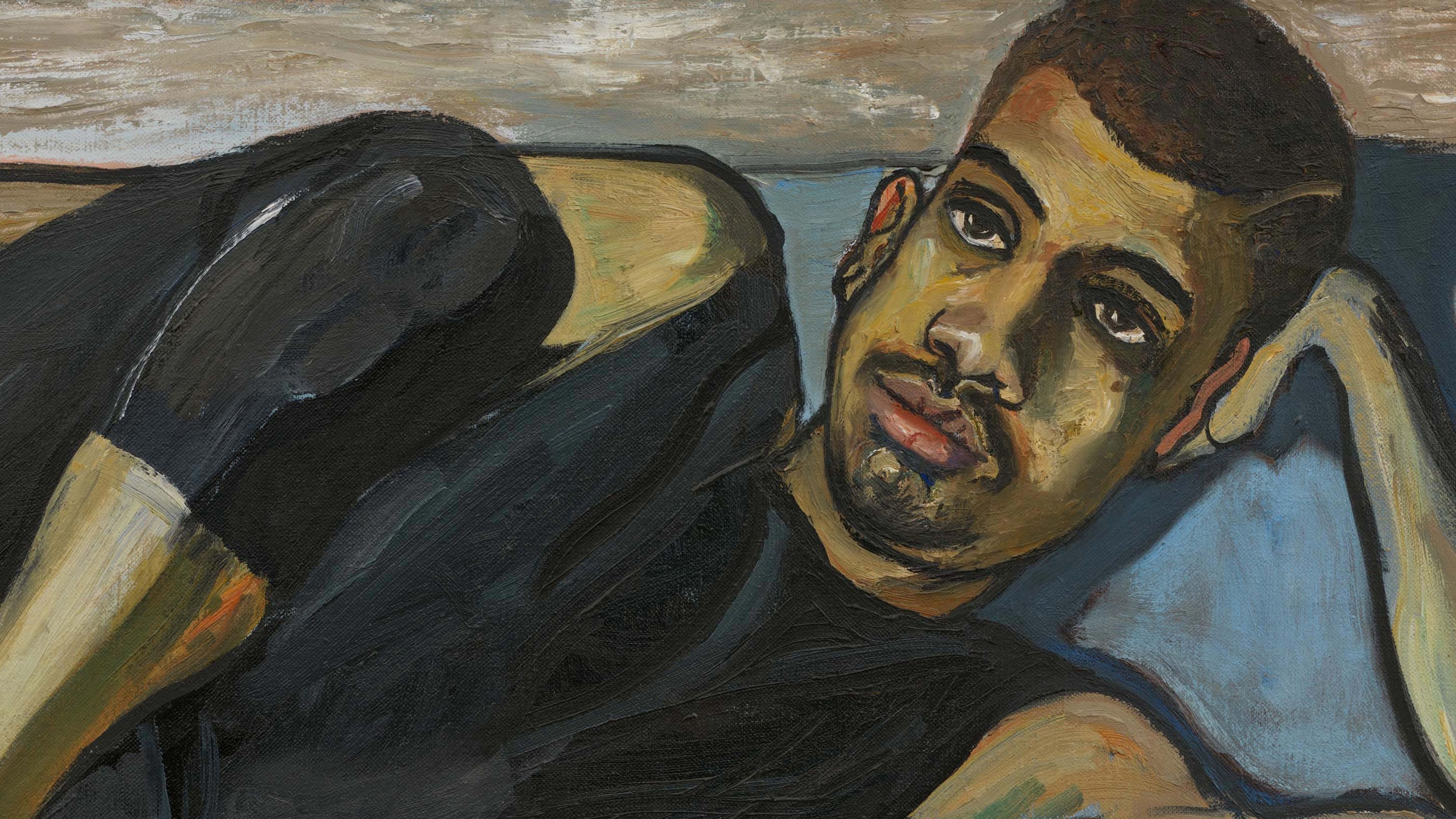

Alice Neel, Ballet Dancer, 1950 (detail)

“Many of Neel’s male sitters seem to exude a gay or queer subjectivity, [such as] the beautifully sprawling figure of Ballet Dancer (1950).... With their distinctive painterly style, Neel’s portraits explore personalities, rather than physical types; they also memorialize figures historically excluded from the art world, which has long devalued depictions of people of color, advancing a more capacious vision of community.”

—Andrianna Campbell, art historian, in Frieze, 2017

Alice Neel’s Adrienne Rich (1973) and Mary Garrard (1977), on view in Alice Neel: People Come First, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2021

Adrienne Rich and her partner Michelle Cliff, n.d. Photographer unknown

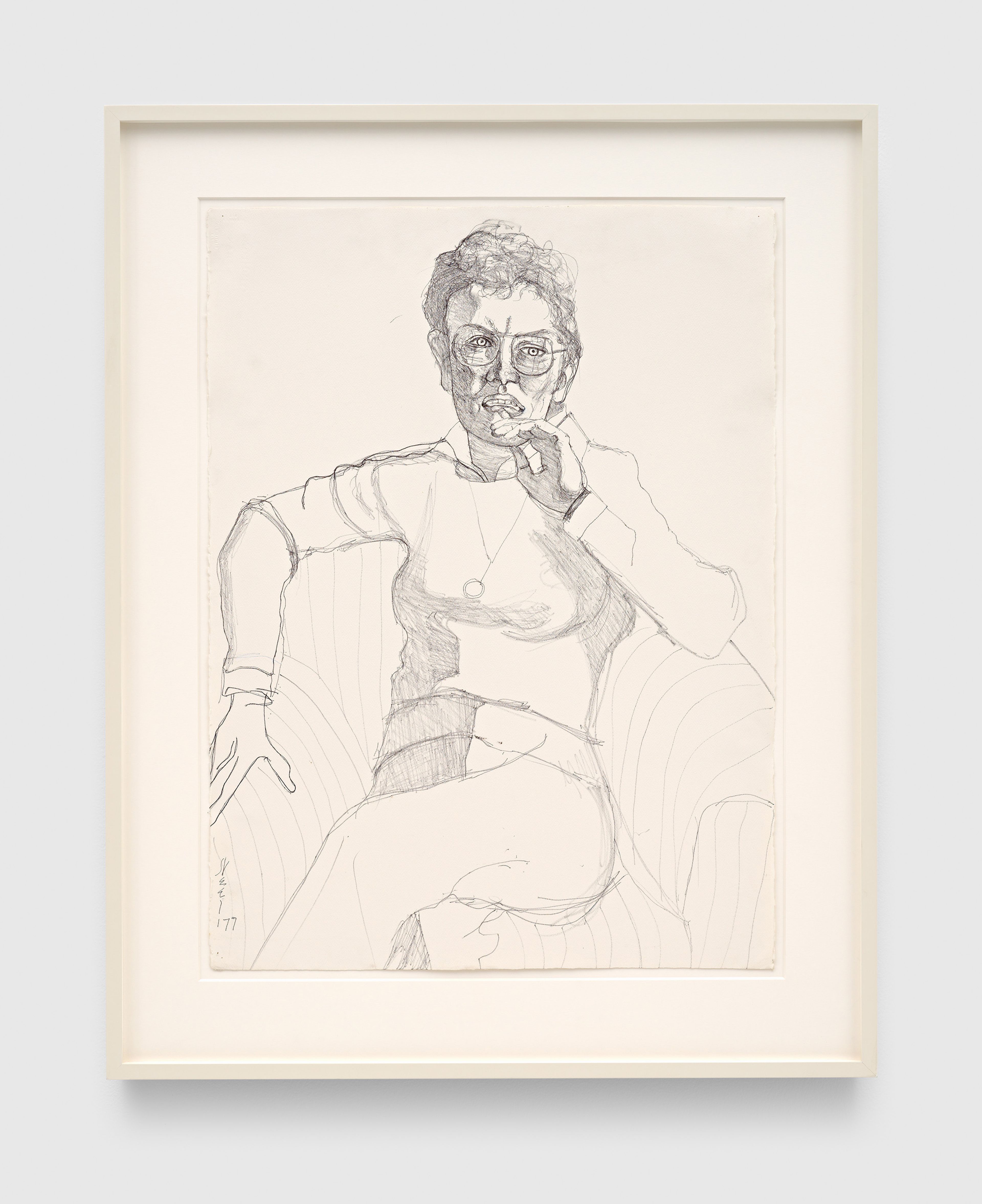

While the exhibition primarily comprises paintings, drawing was a fundamental, stand-alone component of Neel's practice, persistently pursued alongside painting. The medium enabled Neel to capture the immediacy of her visual experience—whether in front of her sitters or on the city streets—while also affording a greater sense of experimentation and informality.

One drawing depicts American poet and feminist Adrienne Rich, who had relocated to New York City in 1966. Rich is best known for her seminal 1980 essay “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” in which she critiques the assumption that heterosexuality is the default or “natural” sexual orientation for women. Rich argues that this assumption is socially constructed and perpetuated by patriarchal institutions, effectively marginalizing and erasing lesbian existence and experiences and permanently rendering women in subordinate roles. The essay has had a profound impact on feminist theory, LGBTQ+ studies, and broader discourse on sexuality and gender.

Alice Neel, Mary Garrard, 1977 (detail)

Alice Neel’s Mary Garrard (1977), on view in Alice Neel: Hot Off the Griddle, Barbican Centre, London, 2023

“In confronting me with more of my identity than I wished at the time to share, she may have pushed me to be a bit more open, though at first it was by way of confronting her back. The portrait has a bit of that in it—a little, ‘how dare you?’.... In each of us, there are suppressed and minimized parts of our personalities that sometimes need expressing. In pulling those out of me, Alice did me a favor.”

—Mary Garrard, feminist scholar and art historian, in her essay “Alice Neel and Me”

Installation view, At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World, David Zwirner, Los Angeles, 2024

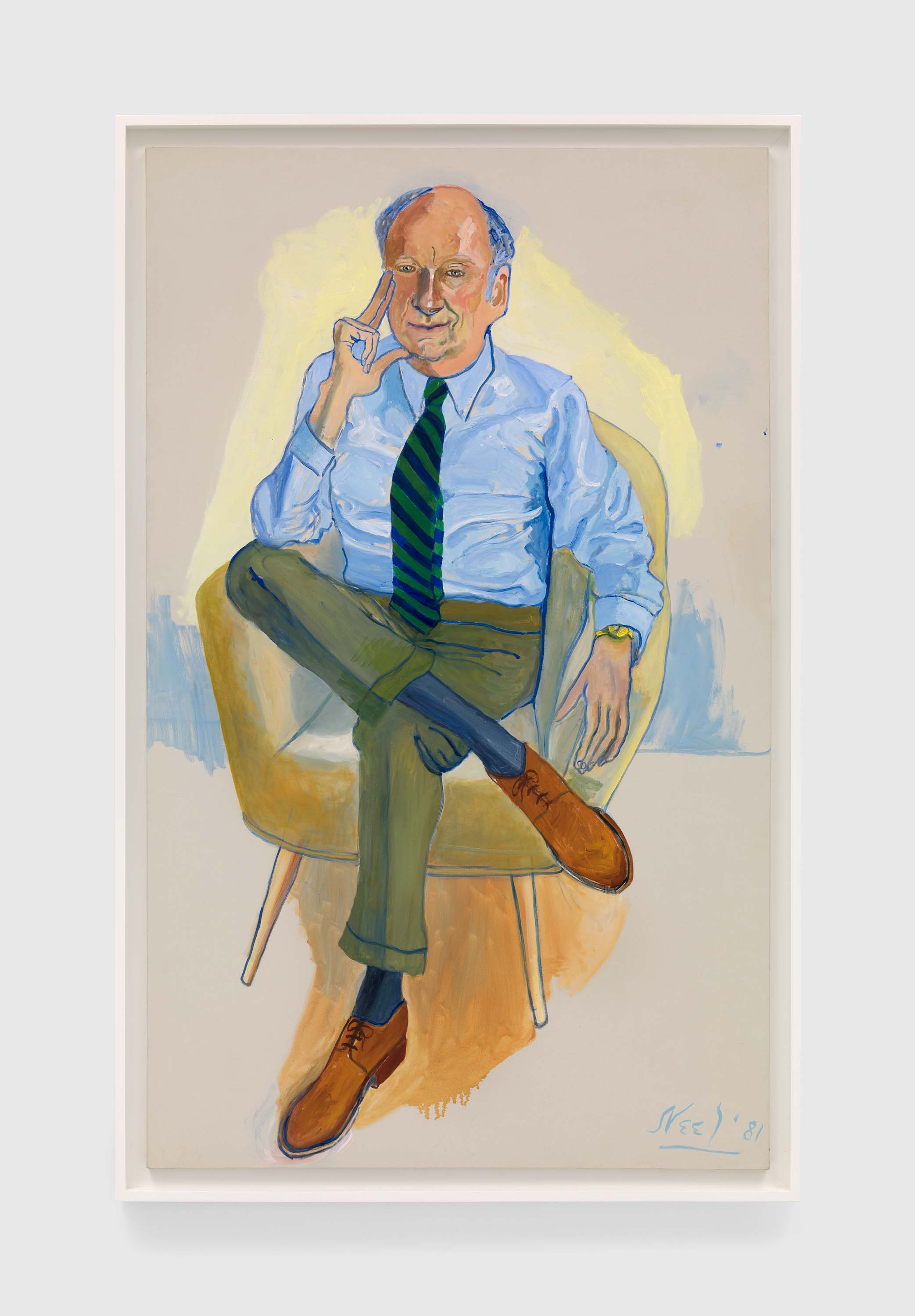

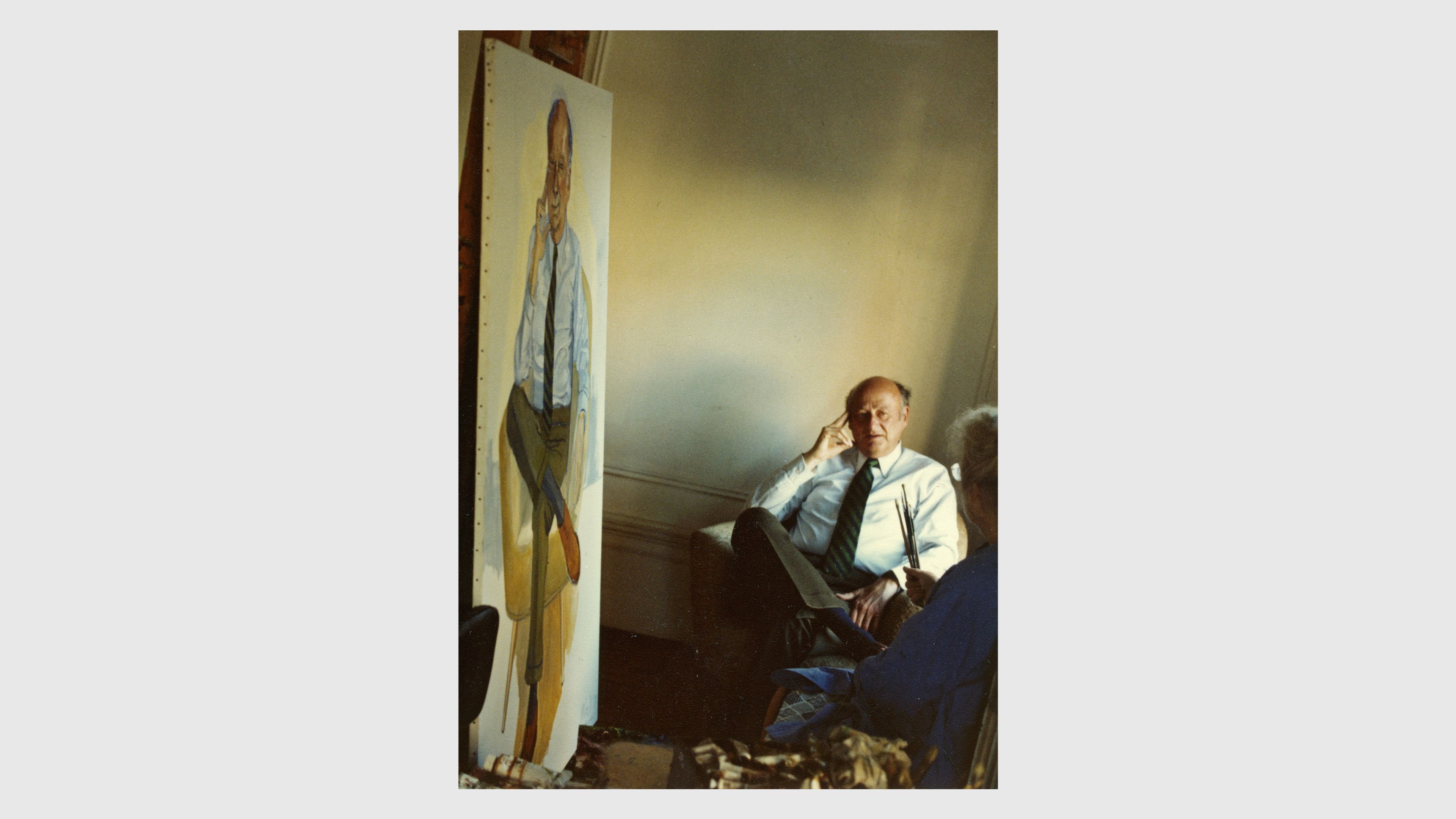

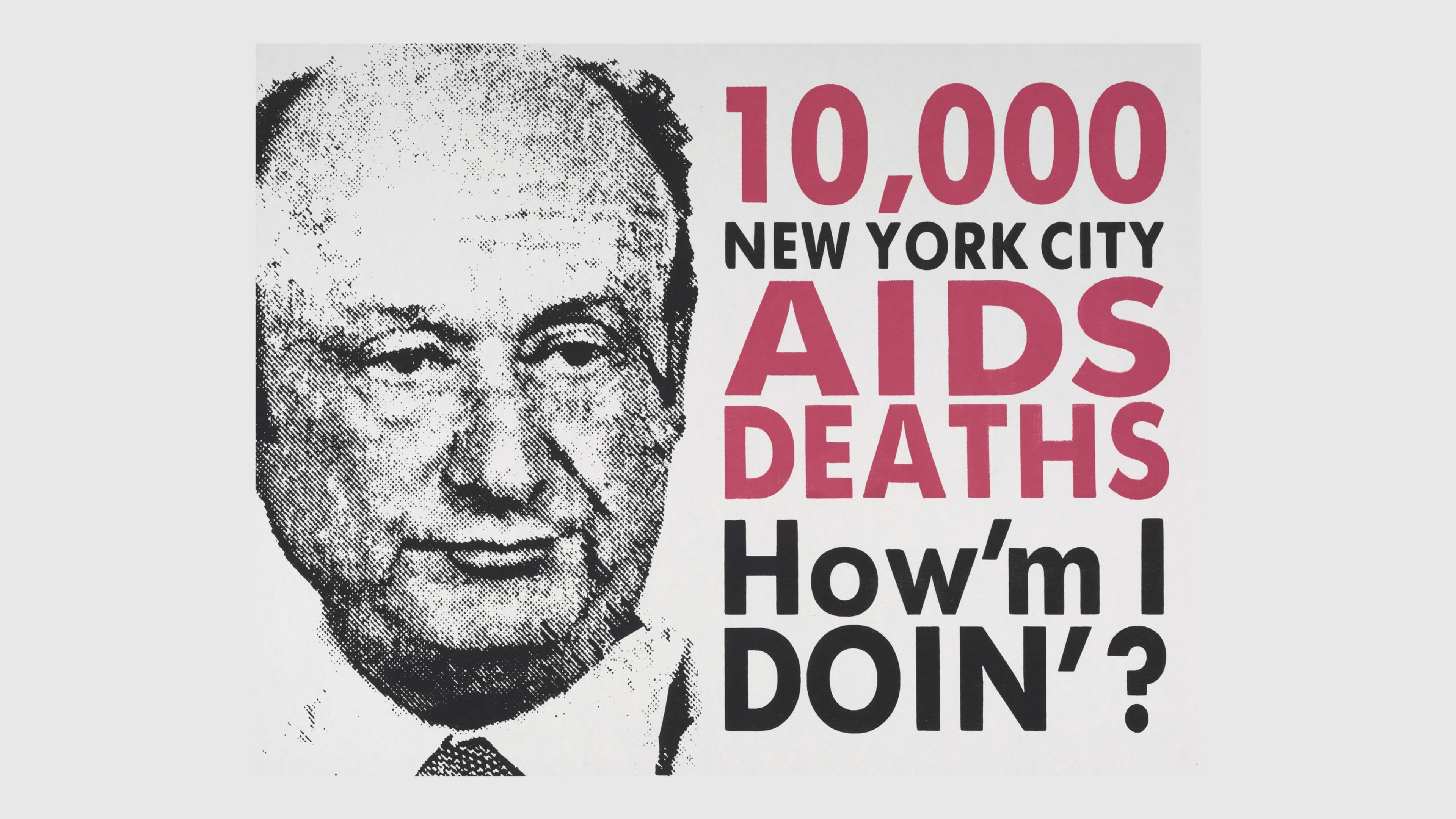

“The present exhibition promotes a kind of ideal queer community where Koch and others can join ... in a universe framed by freedom, and illuminated by the artist’s profound genius for understanding what it is that makes us human—and different.”

—Hilton Als

Bella Abzug and Ed Koch at the introduction of the first gay-rights bill in Congress, 1974. Courtesy the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force records, #7301. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, New York

Neel with Henry Geldzahler (1967) and Bella Abzug (1976) at the exhibition Women Painters and Poets: Visual Artists Coalition, Loeb Student Center, New York University, 1977. Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel

Alice Neel’s Bella Abzug (1976), on view as part of The Sister Chapel (1974–78), P.S.1 Institute for Art and Urban Resources, Long Island City, New York, January 1978. Photographer unknown. Courtesy Andrew D. Hottle

Bella Abzug at the Women’s Liberation Day parade in New York, on the fiftieth anniversary of women winning the vote in the United States, February 2, 1970. Courtesy the Hulton Archive, Keystone/Getty Images

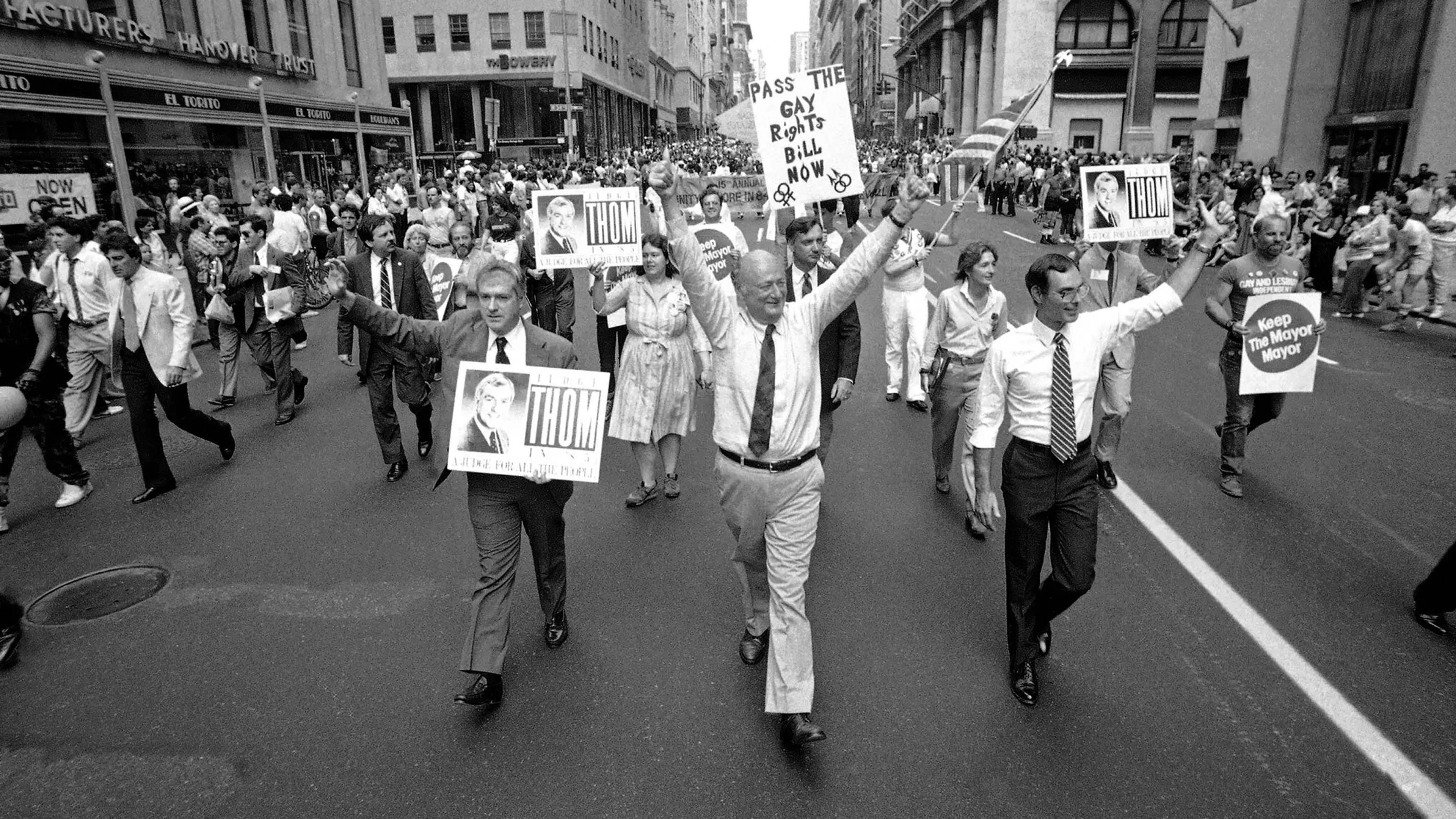

Bella Abzug was nicknamed “Battling Bella” for her role as a lawyer, social activist, and for her involvement with the women's movement as a leading figure in ecofeminism. As a lawyer, Abzug focused on labor rights, tenant rights, and civil liberties cases. She was first elected to the House of Representatives in 1970 and was one of the first members of Congress to support gay rights. Abzug, along with Mayor Ed Koch, was responsible for proposing the gay-rights legislation known as the Equality Act of 1974.

At the debut of The Sister Chapel in 1978, where this painting was first exhibited, Neel explained that the depiction of Abzug’s breasts were meant to show that “she would nurture the electorate.” As Abzug herself described, being a feminist was “as natural as breathing, feeling, and thinking.”

“She felt a great deal of respect for the community that she lived in and for the people that she was around. And you can see and feel that love and respect in the paintings.”

—Miguel Luciano, artist

Andy Warhol and Jackie Curtis, 1969. Photo by Jed Johnson. Courtesy The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh

Alice Neel, Jackie Curtis as a Boy, No. 2, 1972 (detail)

Alice Neel with Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd in front of Neel’s painting Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd (1970) at Moore College of Art, 1971. Photographer unknown. Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel

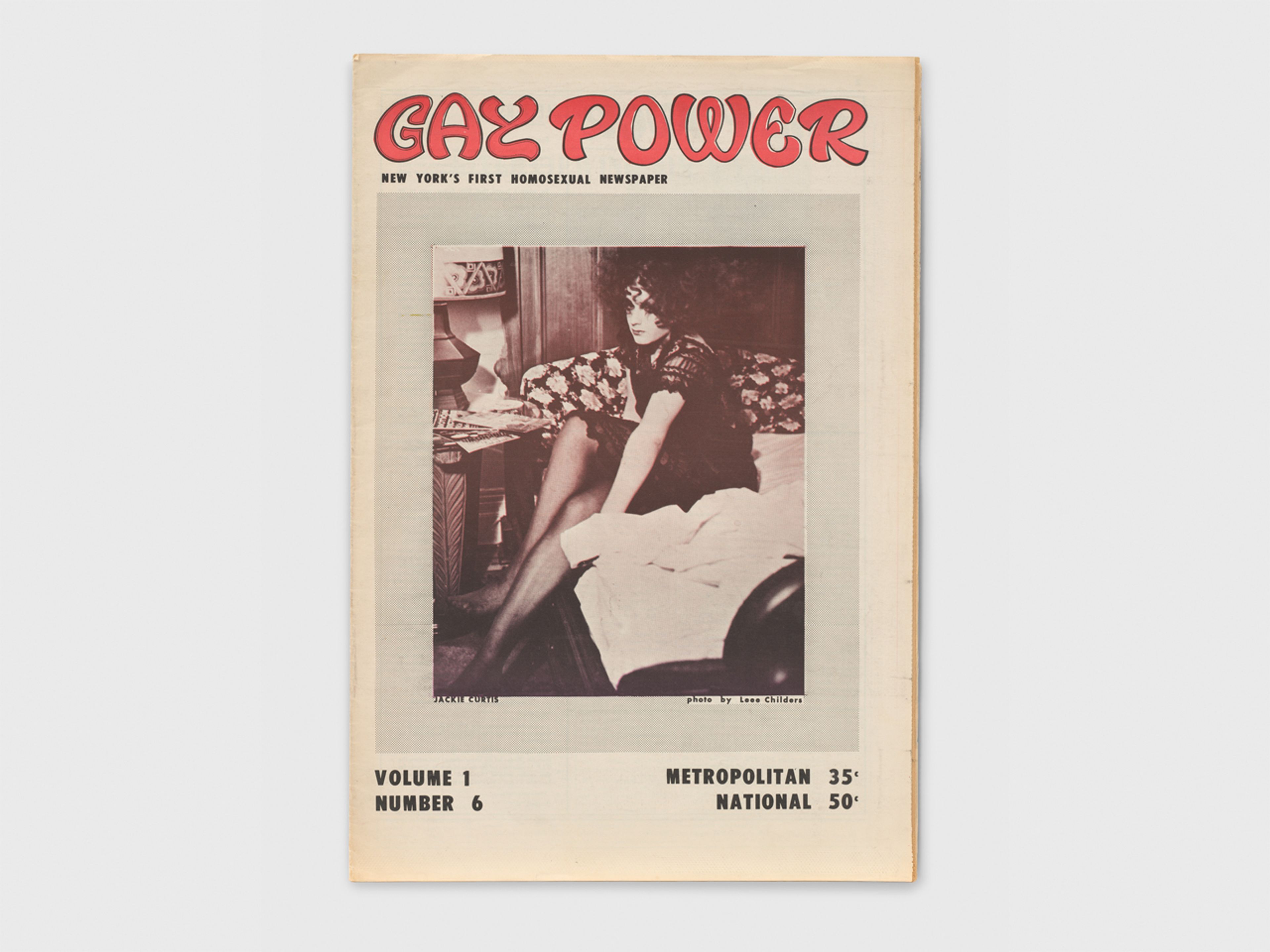

Jackie Curtis on the cover of Gay Power 1, No. 6, 1969. Photo by Leee Childers. Collection of NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

In 1972, Neel painted Jackie Curtis, a performer, playwright, and poet who was friends with the artist and was also involved with Andy Warhol's Factory. Curtis performed both as a woman, in drag, and as a man throughout his career. Here, Neel uses shades of bright blue, red, orange, and purple to render Curtis’s face, which echoes the make-up that he would have worn onstage. This is one of two nearly identical paintings Neel made of Curtis; the other is in the collection of Femmes Artistes du Musée de Mougins, France. Curtis also appears in an earlier painting, Jackie Curtis and Ritta Redd (1970), that is in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio.

In Als’s catalogue introduction, he writes: “For a long time I thought that being gay was politics enough—difficult enough—but then when I looked at Neel’s portraits of Jackie Curtis and others, I saw the disaster and beauty inherent in becoming a self and realized it occurs not only within the subject’s body, but in the eye of the world. I loved Geldzahler and others for their outright queerness even as I recoiled from their love of hierarchy and power. Neel’s portraits of queer thinkers, artists, and beings taught me that what I was drawing back from, ultimately, was affect, and what I was looking for—what Alice Neel painted—was the collective uncanny: how, despite the odds, we persisted in being a self no matter how you or the world labeled it.”

“I am not a boy, not a girl, I am not gay, not straight, I am not a drag queen, not a transsexual—I am just me, Jackie.”

—Jackie Curtis

Installation view, At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World, David Zwirner, Los Angeles, 2024

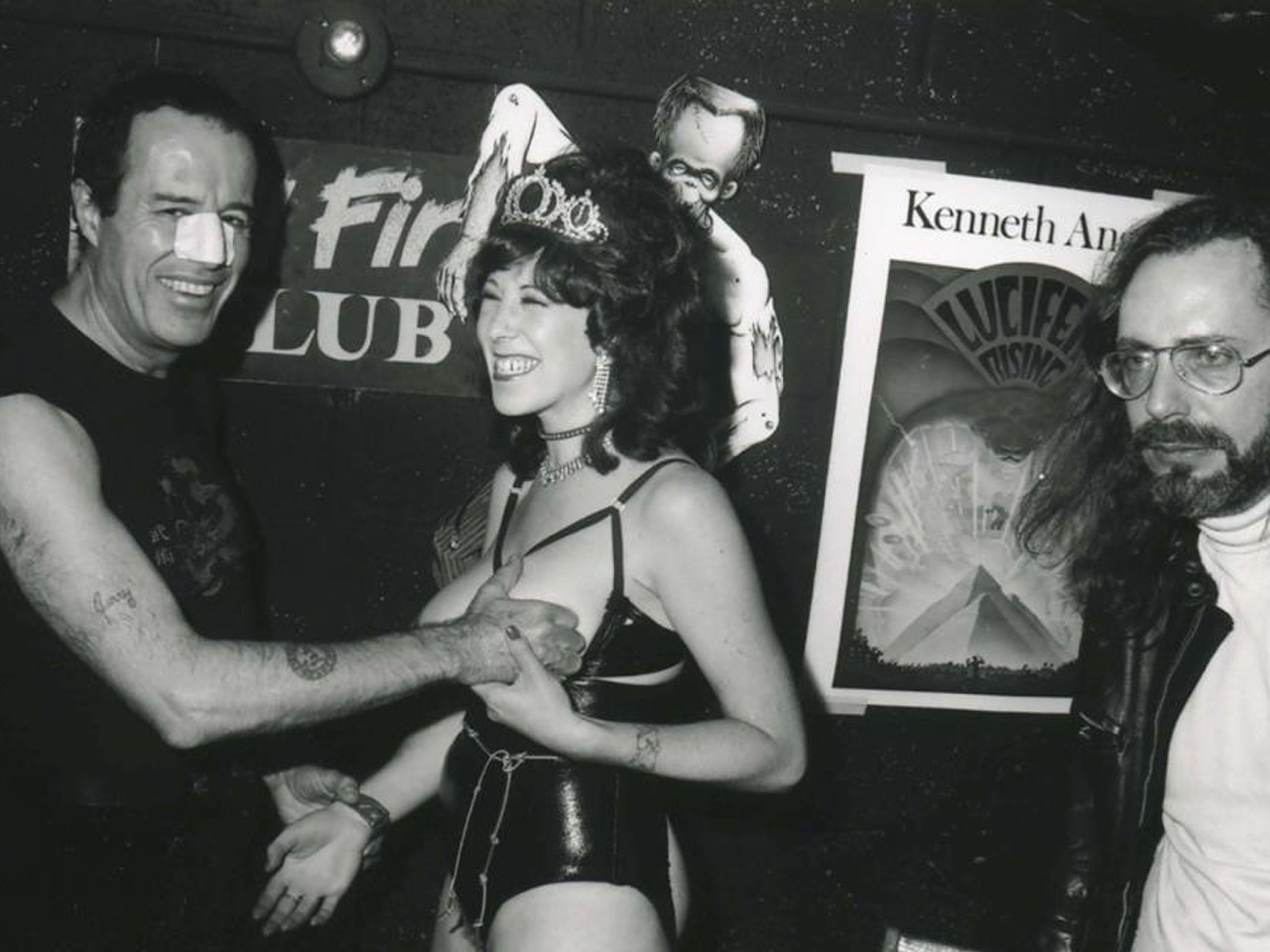

Kenneth Anger, Annie Sprinkle, and Spider Webb at the Hellfire Club, New York, 1980. Photo by Charles Gatewood

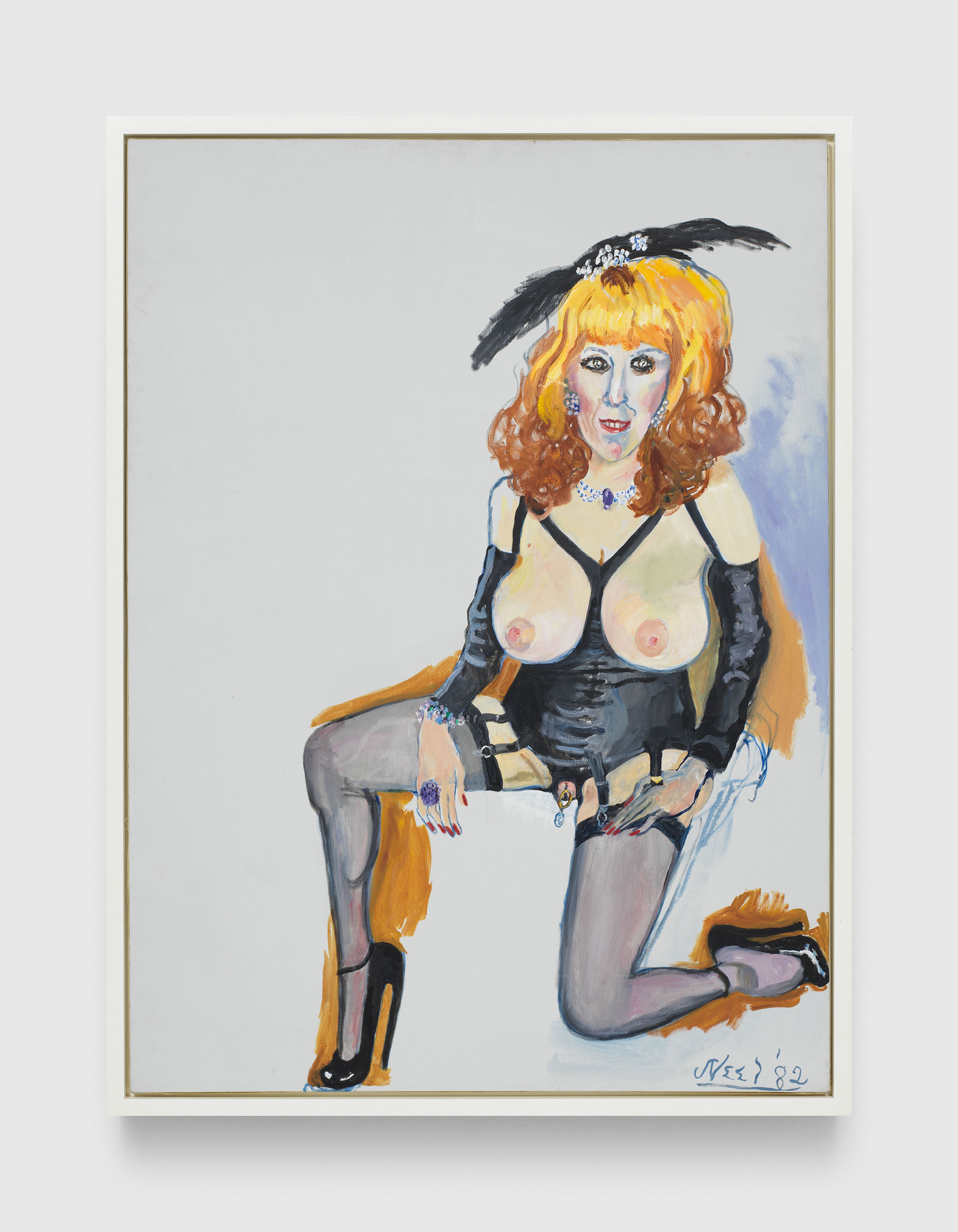

A highlight of the exhibition is Annie Sprinkle (1982), which depicts the porn star and burlesque performance artist in the leather outfit of a dominatrix. The unabashed quality of this image demonstrates the felicitous communion Neel had with the people she painted.

Sprinkle wrote about her experience sitting for Neel: “I was in the mainstream sex industry—a professional call girl, a porn star, and a sexual-rights activist. [Alice] was fascinated by the work I was doing in pornography, sex workers' rights, trying to decriminalize prostitution, so she asked if she could paint me, and I said of course.... She was passionate about every little thing.... Alice brought the lowbrow into the highbrow. We both got a thrill out of her being 83 or 84 and me being the sex-goddess slut that I was.”

“This provocative late-career portrait—one of the artist’s last before her death—is perhaps her most revealing for its remarkable restraint.... This is a picture of a woman seeing, studying, and capturing the power of another woman—provocateur to provocateur. In that sense, the work is also a kind of self-portrait, a conduit for their shared and respective strength, both as artists and as women.”

—Evan Garza in their catalogue essay in At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World

Dennis Florio with Annie Sprinkle at a party celebrating Sprinkle's graduation from School of Visual Arts, New York, after she earned a BFA in photography, 1986. Courtesy Annie Sprinkle

Marcel Proust. Courtesy Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

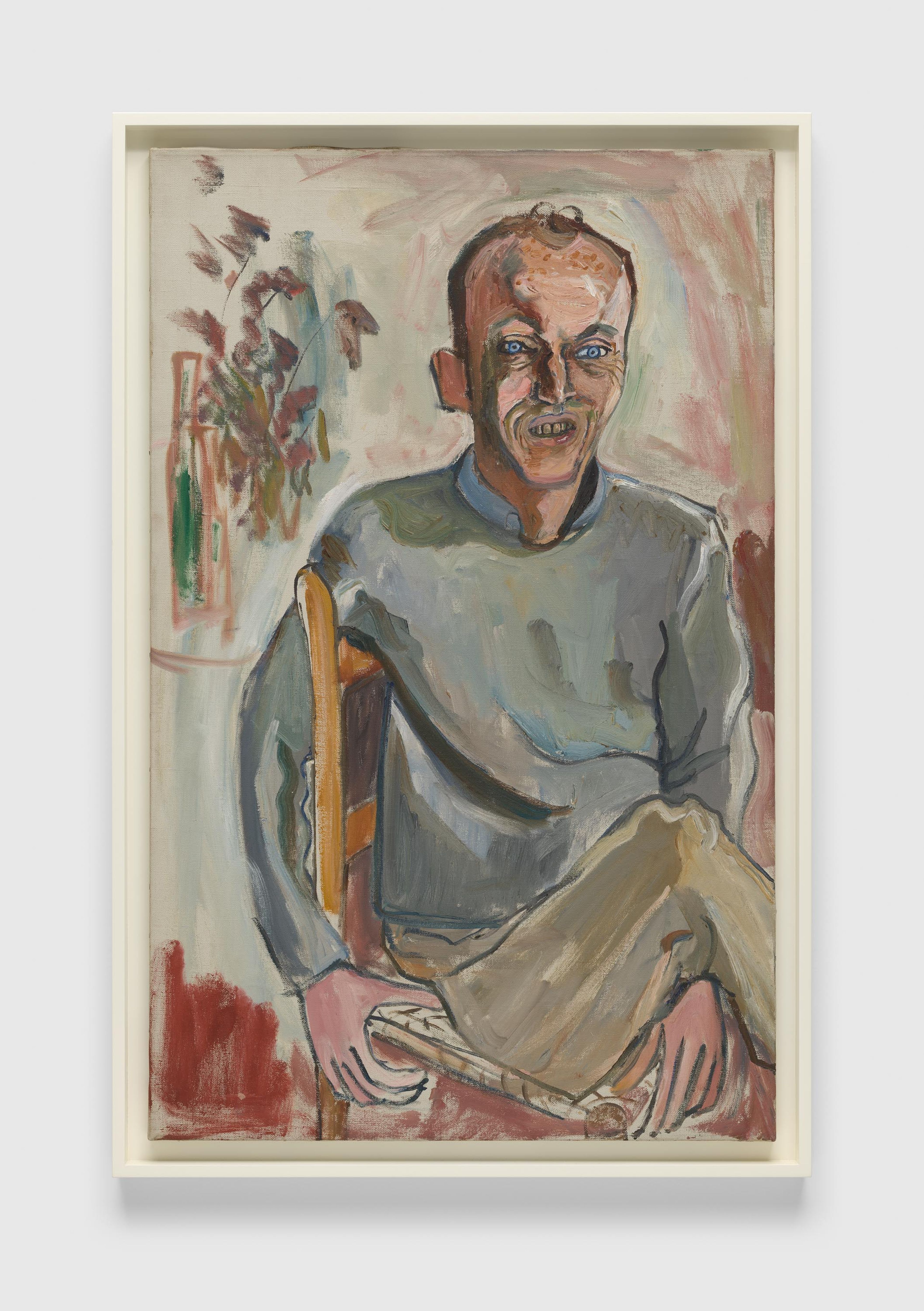

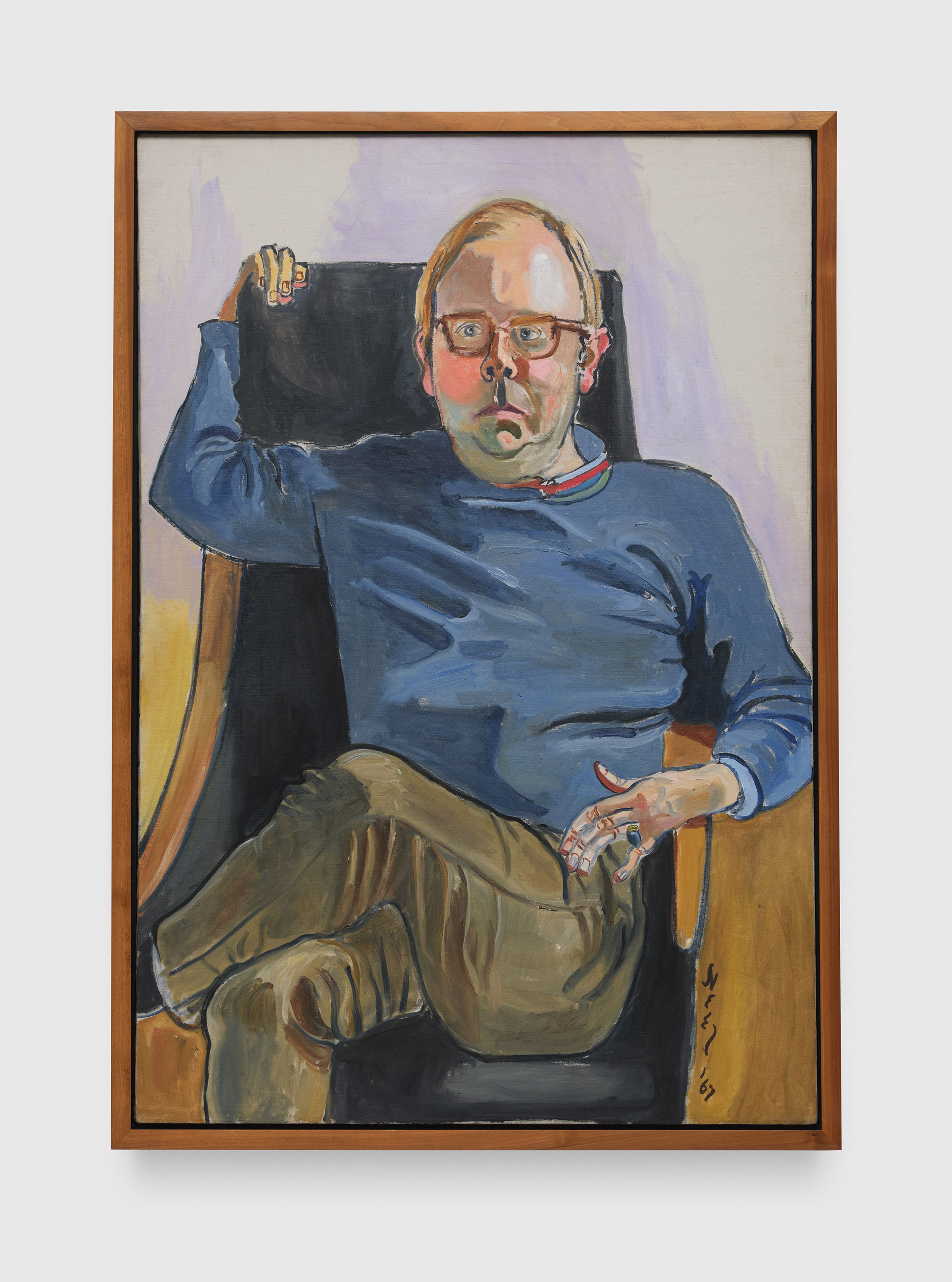

In 1978, Neel painted Dennis Florio, a fine-art framer she met through Annie Sprinkle. In her 2008 book A Short Life of Trouble: Forty Years in the New York Art World, art historian Marcia Tucker describes him: “Dennis Florio, whom I'd first met because he was a framer for the Whitney, lived his entire life as though he were onstage. He was a loyal member of the Theme Luncheon of the Month Club, an extrovert, a rake, and an outrageous wit. It took a while for his friends to realize that he was suffering from AIDS-related dementia, because causing a scene was something he did regularly, just for fun. Only when the police had to carry him out of his apartment and lock him up for disturbing the peace did we know that something was seriously wrong. His mind was clear, though, when with his last breath he whispered to the crying friends gathered around his bed, ‘Whatever you do, make sure I'm cremated. Nothing can get me to go back to New Jersey!’”

Alice Neel, Dennis Florio, 1978 (detail)

“In Neel’s rendering of Dennis Florio, with handlebar moustache and red velvet suit, he looks like Proust, eyes burning their durée into us.”

—Wayne Koestenbaum in his catalogue essay in At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World

Geoffrey Hendricks with Alice Neel’s Brian Buczak (1983), 1988. Photographer unknown. Courtesy the Geoffrey Hendricks Estate

Alice Neel and Brian Buczak celebrating Neel’s eightieth birthday, 1980. Photo by Geoffrey Hendricks. Courtesy the Geoffrey Hendricks Estate

Many of Neel’s sitters in the 1970s and ’80s would eventually fall victim to HIV/AIDS, including artist Brian Buczak (1954–1987), who was the partner of Fluxus artist Geoffrey Hendricks. Buczak and Hendricks met Neel in the fall of 1977 at Rutgers University in New Jersey, where Hendricks taught at the time, following a slide lecture Neel delivered on campus. Buczak and Neel maintained a friendship over the following years, with the younger artist occasionally returning to Neel’s apartment for visits. In 1986, he was diagnosed with AIDS, and he died in 1987 at the age of thirty-two.

“In addition to Brian Buczak, AIDS would claim several of Neel's sitters.... Given Neel’s innate understanding of life’s inexplicable cruelties, one can easily imagine, had she lived a bit longer, her facile and fearless brush taking the disease head-on.”

— Randall Griffey, Alice Neel: People Come First

Installation view, At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World, David Zwirner, Los Angeles, 2024

Inquire about works by Alice Neel