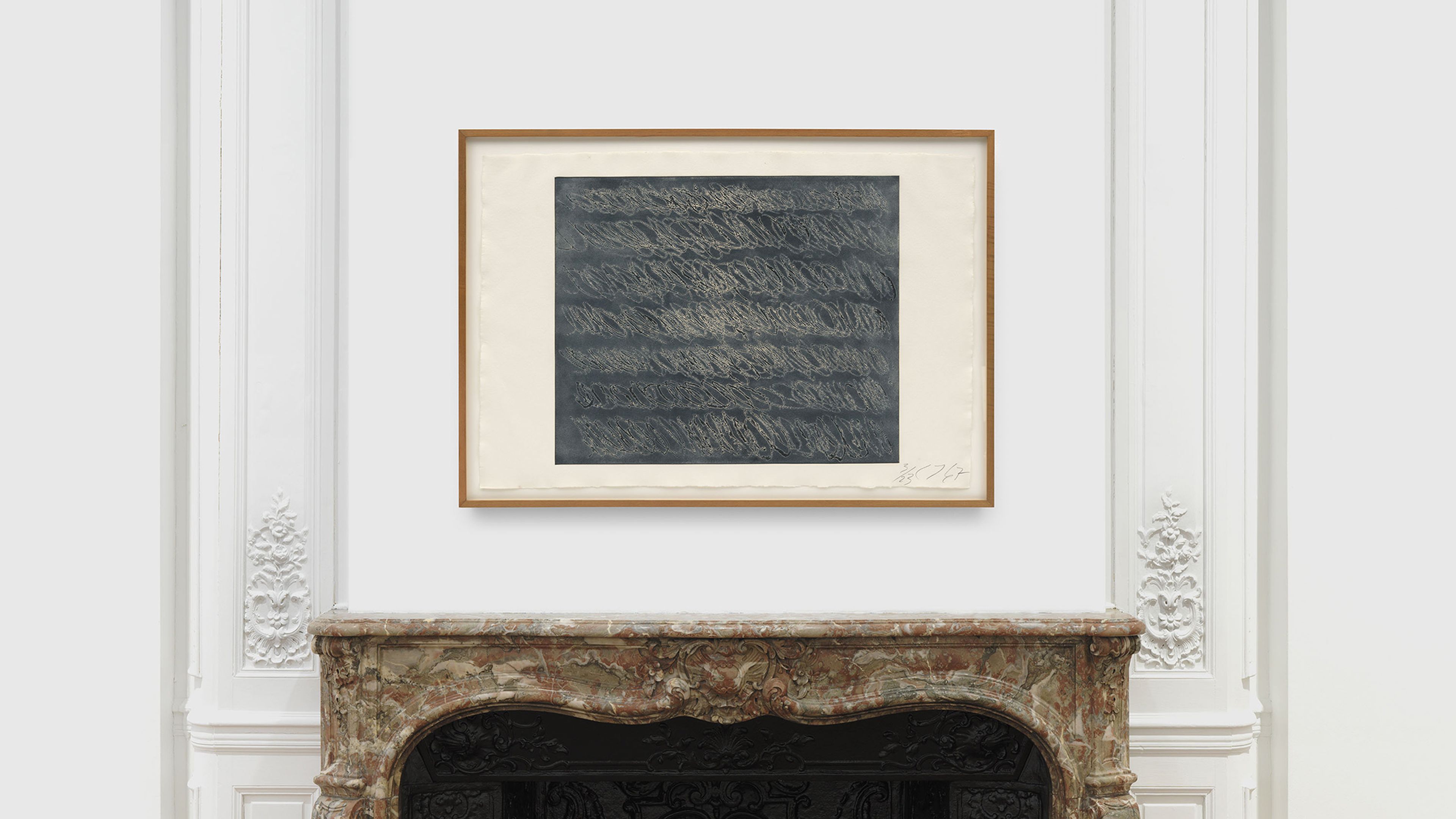

Exceptional Prints: Cy Twombly

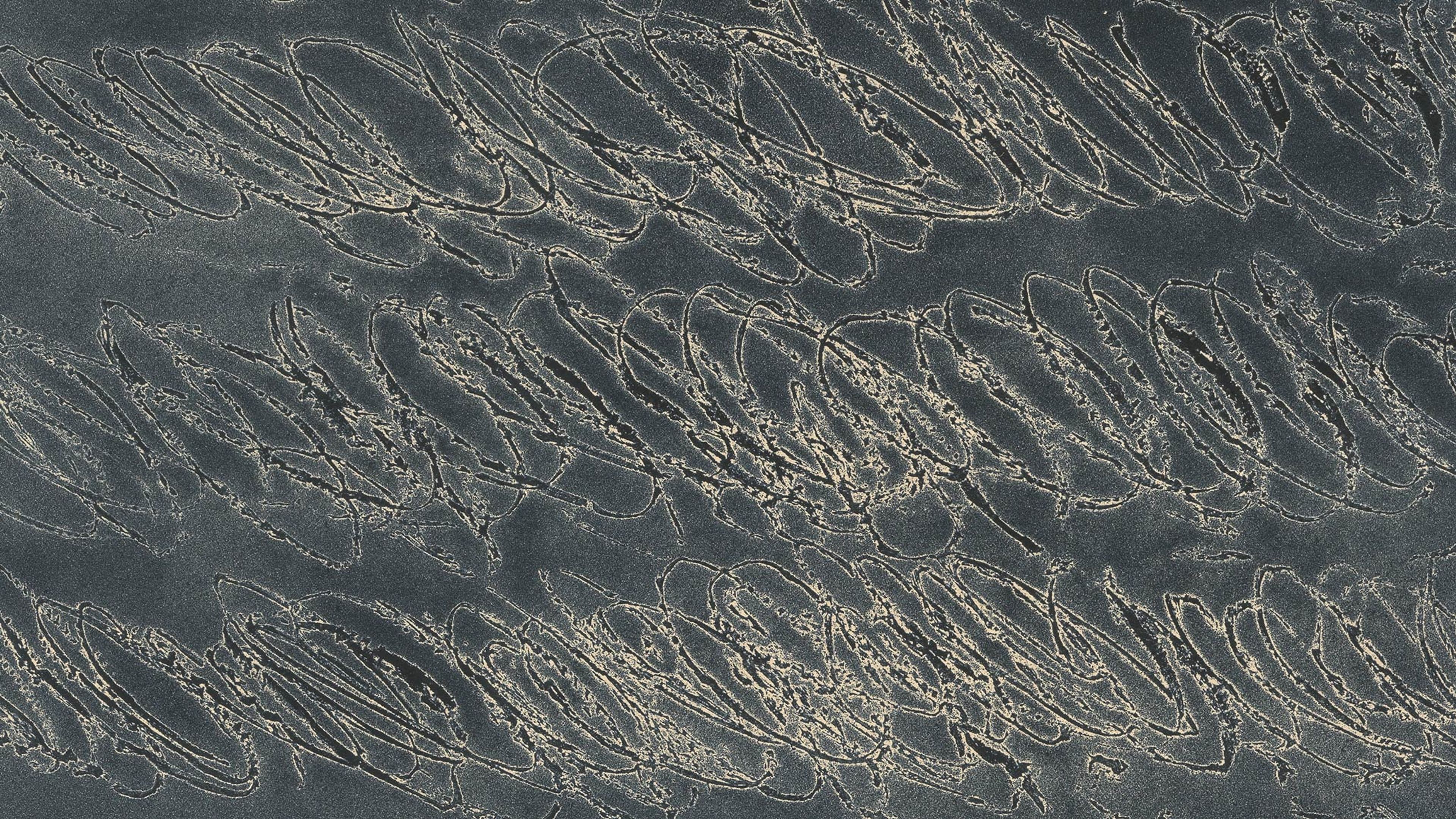

Untitled II, 1967

Intaglio with etching and open-bite aquatint on White J. Green handmade paper 27 1/2 x 40 1/2 inches 69.9 x 102.9 cm

Installation view, Prints: Acquisitions 1973–1976, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1976. Untitled II (1967) is visible at left. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY. Photo by Kate Keller

Cy Twombly, Untitled II, 1967 (detail)

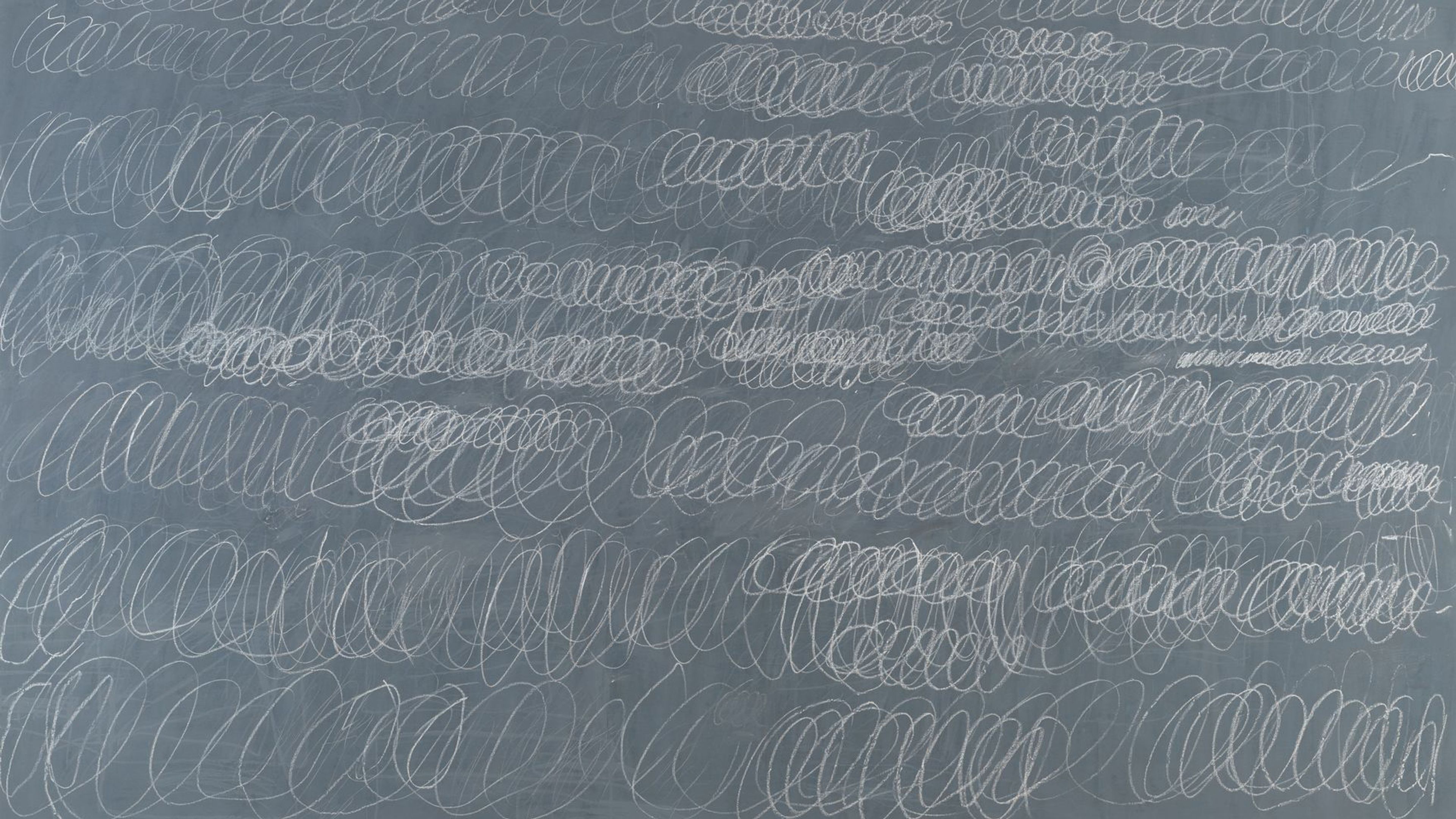

Cy Twombly, Untitled, 1967. The Menil Collection, Houston. © Cy Twombly Foundation

Cy Twombly, Untitled (New York City), 1968. Private collection. © Cy Twombly Foundation

Cy Twombly, Untitled, 1970. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. © Cy Twombly Foundation

Untitled II is an early example of the looping line that is now iconic in Twombly’s oeuvre. “A line with a mind of its own” as described by the art historian Simon Schama, this abstract calligraphic motif seems to mimic the cadence of the written word.

In form, Untitled II directly relates to Twombly’s notable series of “blackboard” paintings and drawings, which he created between 1966 and the early 1970s. Twombly's dual engagement with the art-historical idea of the line and the cultural understanding of language resulted in works that are at once extremely nuanced and universally legible.

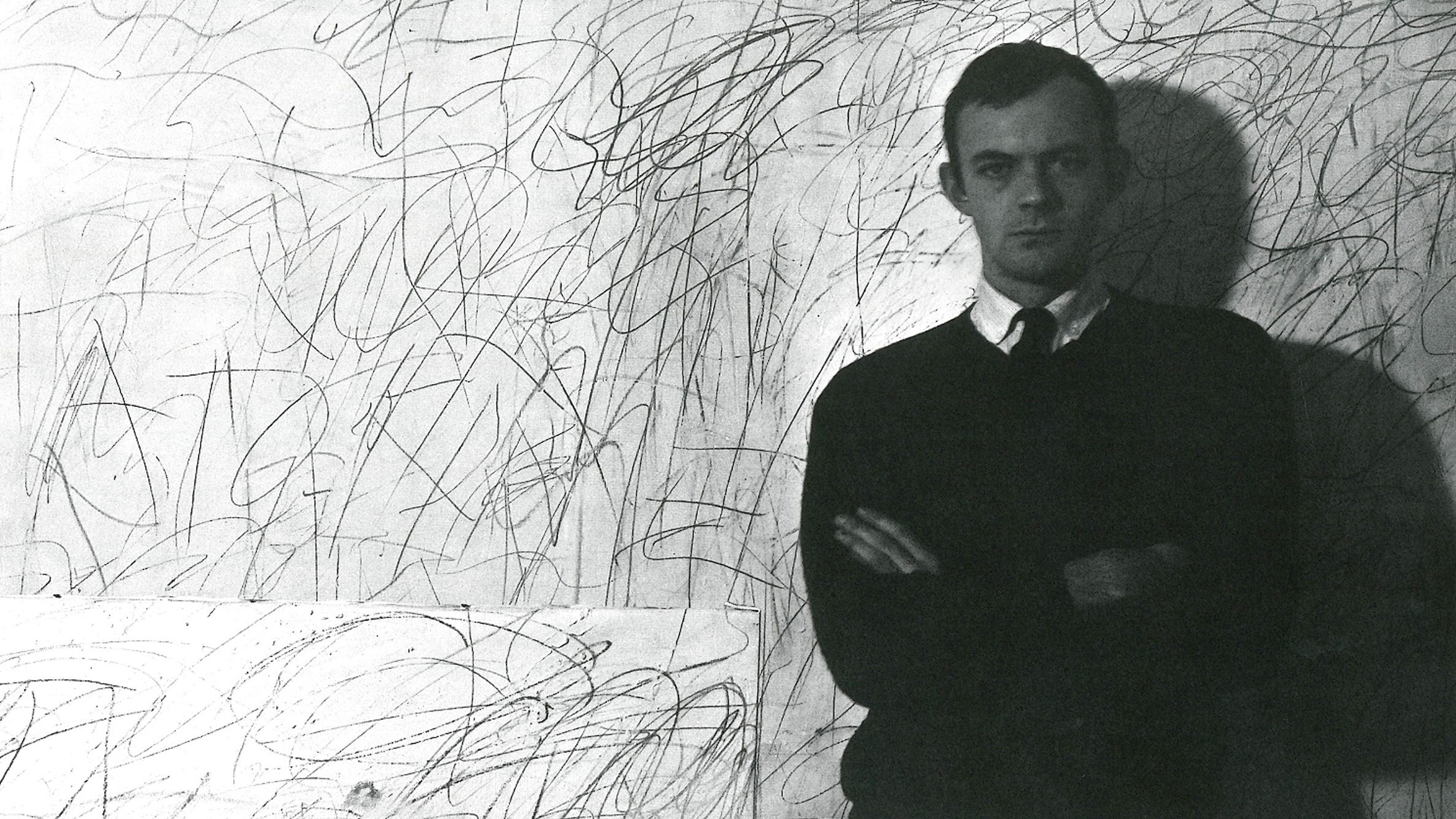

Cy Twombly, self-portrait in his studio on William Street, New York, 1956 (detail). Courtesy Fondazione Nicola Del Roscio

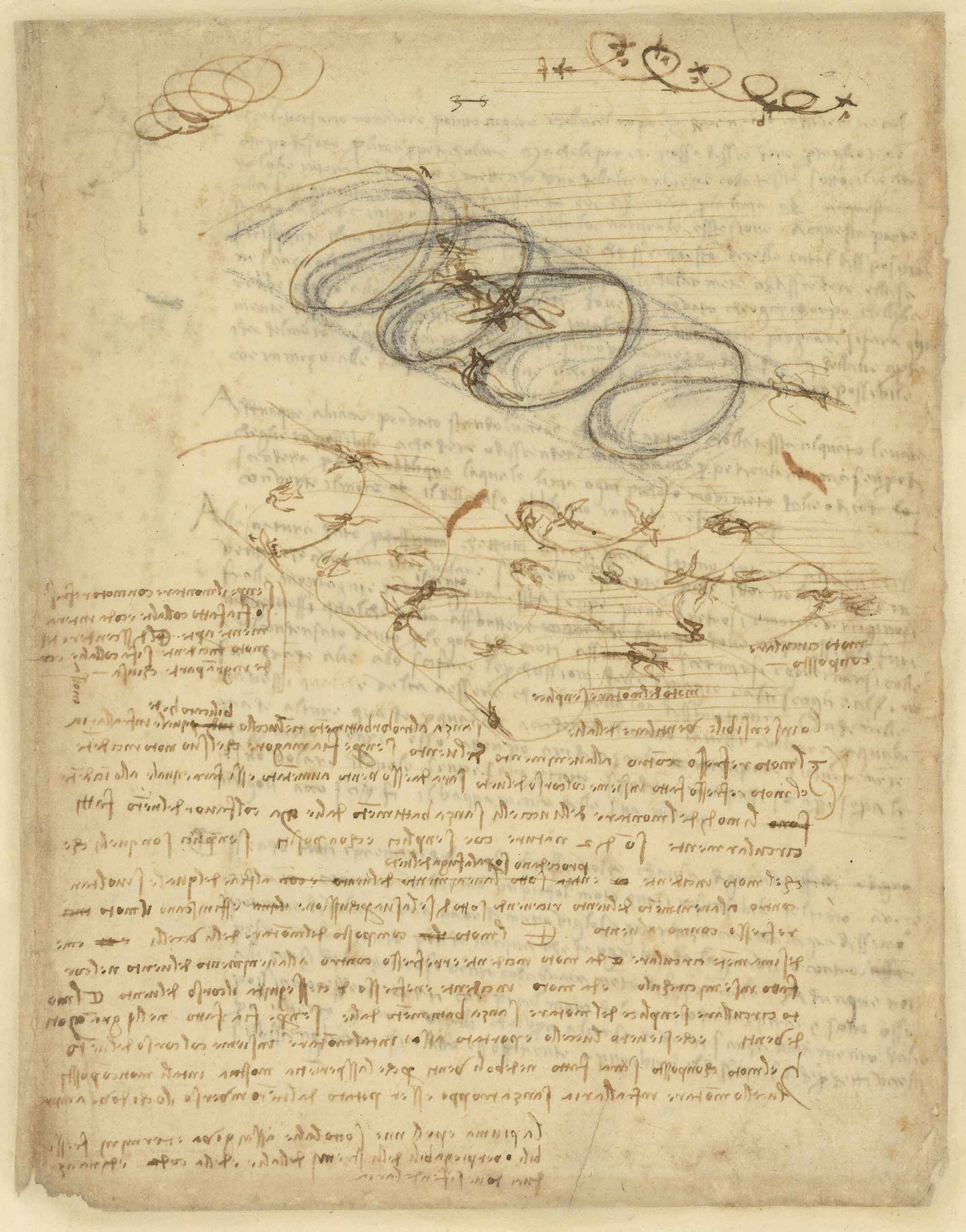

Leonardo da Vinci, Atlantic Codex (Codex Atlanticus), 1478, f. 845 recto

In its approach to capturing space and time through form, Untitled II also reflects the artist’s interest in depictions of dynamic movement in the work of the Italian Futurists, as well as that of Leonardo da Vinci—influences connected with Twombly’s permanent move to Rome in 1957. As Heiner Bastian observes, “Twombly tries to shatter form as well as its concomitant intellectual and narrative history in a kind of relativism, reducing it to a rationality of ‘black and white’ that is at the same time the structural sum of all movement.”

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, 1912. Philadelphia Museum of Art (left); Giacomo Balla, Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, 1912. Buffalo AKG Art Museum, New York (right)

Inquire about Works by Cy Twombly