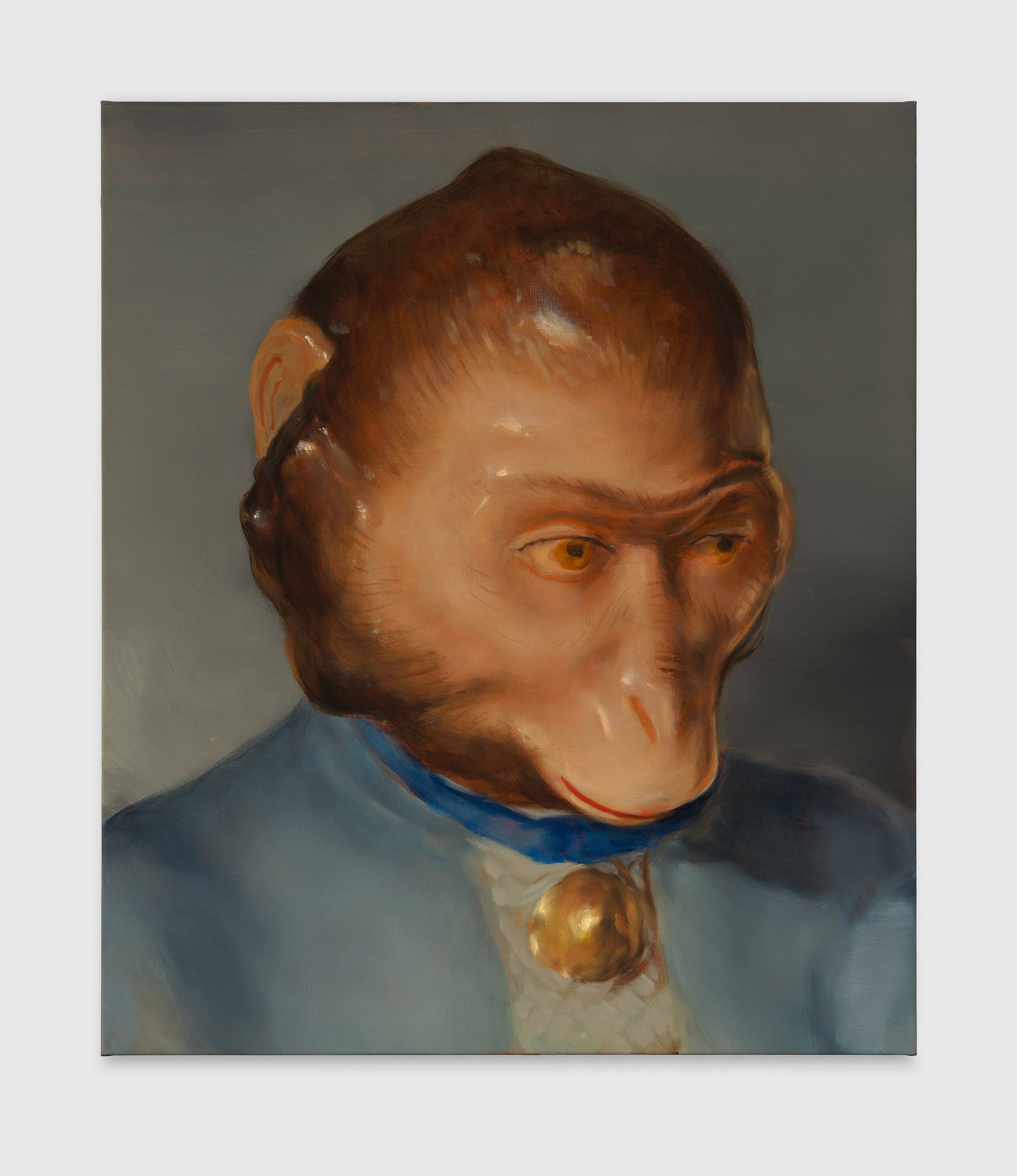

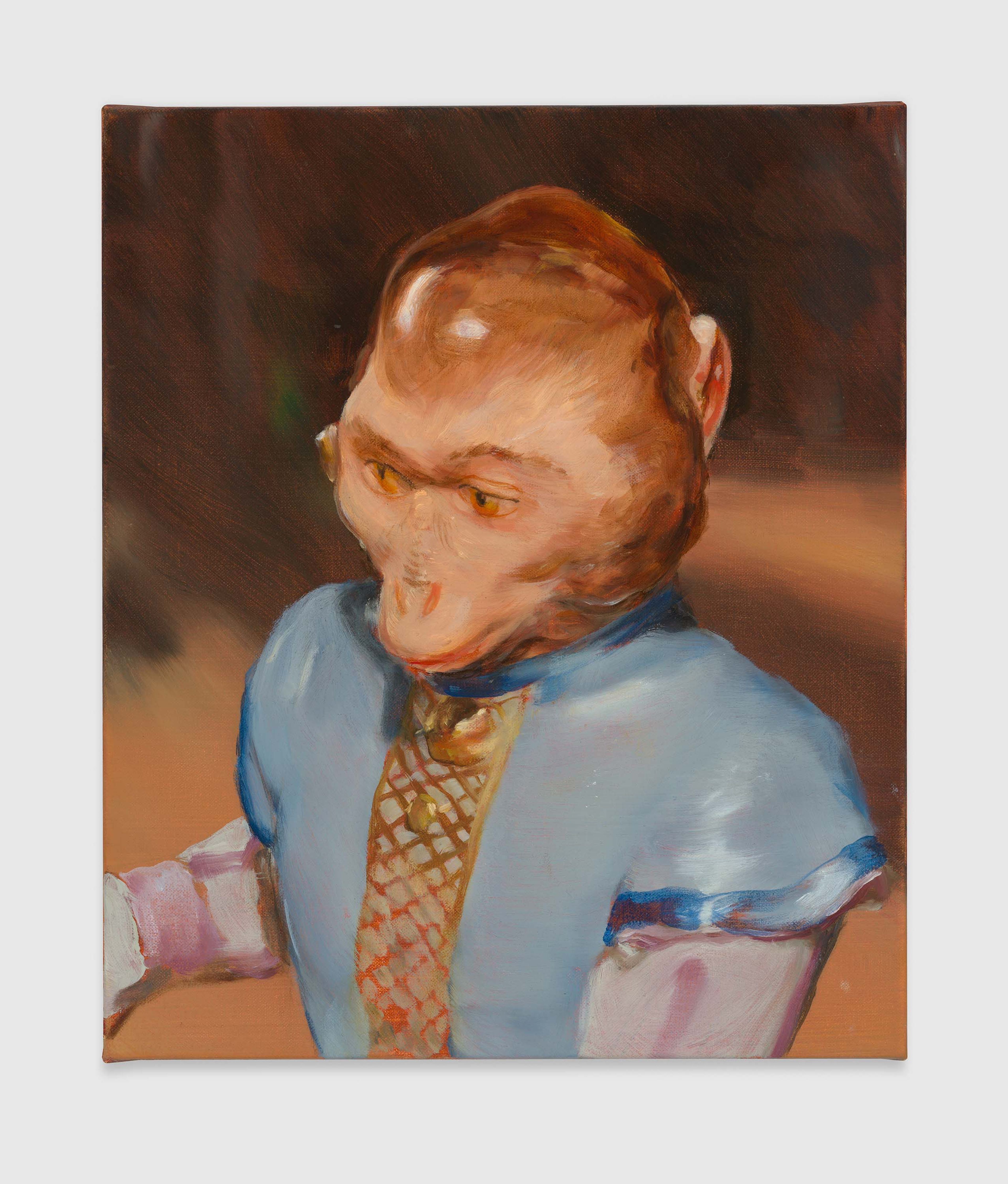

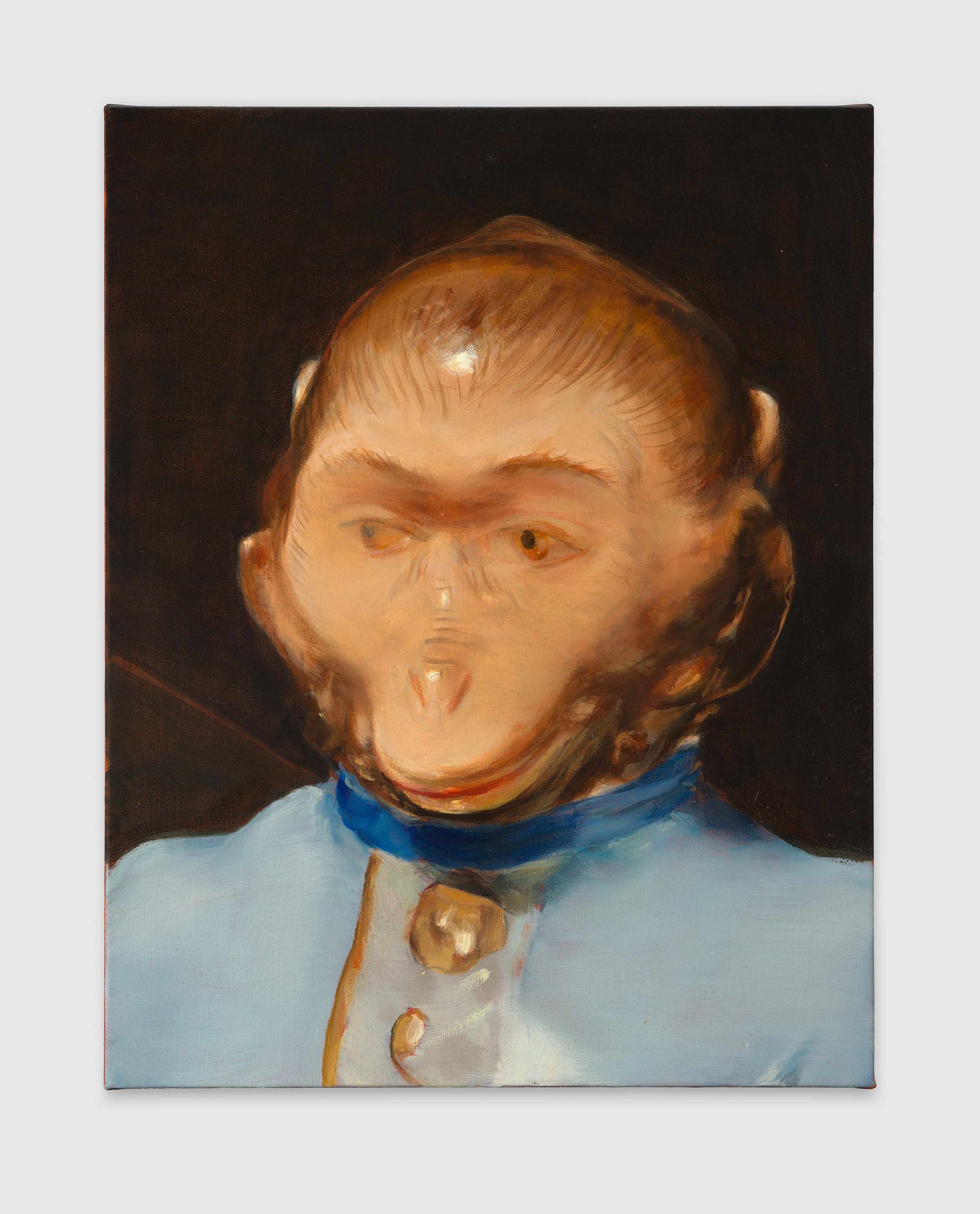

Michaël Borremans: The Monkey

Past

June 6—July 26, 2024

Opening Reception

Thursday, June 6, 6–8 PM

Opening Reception

Thursday, June 6, 6–8 PM

Location

London

24 Grafton Street

London

Artist

Explore

Michaël Borremans, 2024. Photo by Lukas Wassmann

“I try to reflect on life, on humanity, and on contemporary issues, but with the tools that are suitable for me. I like to reflect on contemporary worlds through a historical view.... And I try to relate in terms of the visuals of today and the visuals of yesterday, because they are still present. Wherever you go, where you see culture, you see traces of the past.”

—Michaël Borremans in conversation with Luca Guadagnino, Interview, April 2024

Installation view, Michaël Borremans: The Monkey, David Zwirner, London, 2024

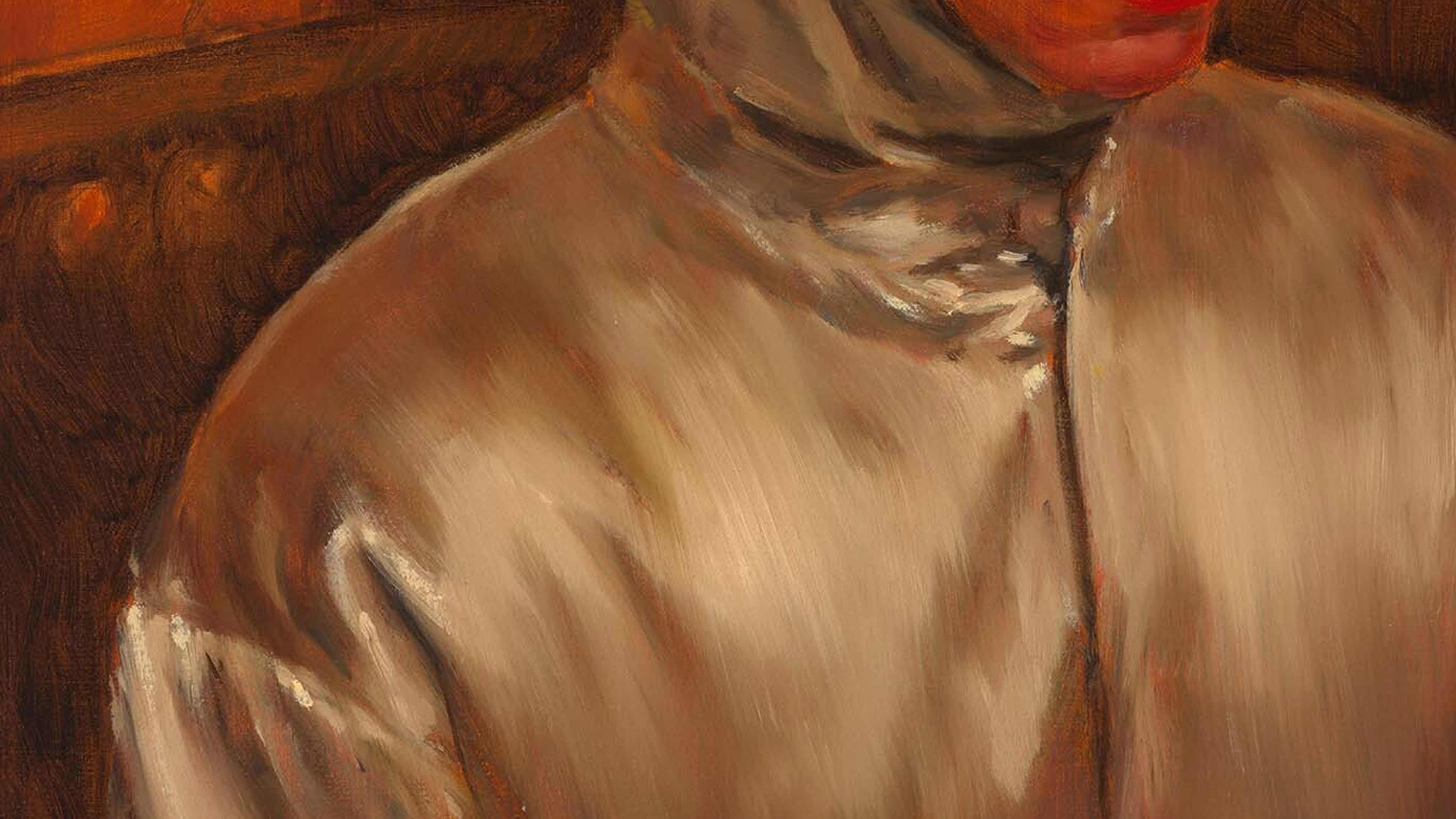

Michaël Borremans, The Monkey, 2023 (detail)

Jean-Baptiste Chardin, The Monkey Painter, 1739–1740 (detail). Collection of Musée du Louvre, Paris

Borremans often tips his hat to Chardin: not so much from a sense of kinship toward the French painter’s compositions and technique (though, no complaints there); rather, it is from a delight in the attitude of his works. Chardin argued that one must paint with feeling, not color. Oftentimes, that feeling spanned exaggerated melancholy and wryness. It was a soft punch, the visual equivalent of a bon mot.

That certainly checks out for Borremans. The artist loves a dry laugh mixed with the somber medium of oil on canvas. In The Monkey, however, the joke comes wrapped in razor blades. This body of work feels sharp and dangerous. The laugh more acidic.

Michaël Borremans, The Glaze, 2007

Michaël Borremans, The Visitor, 2013

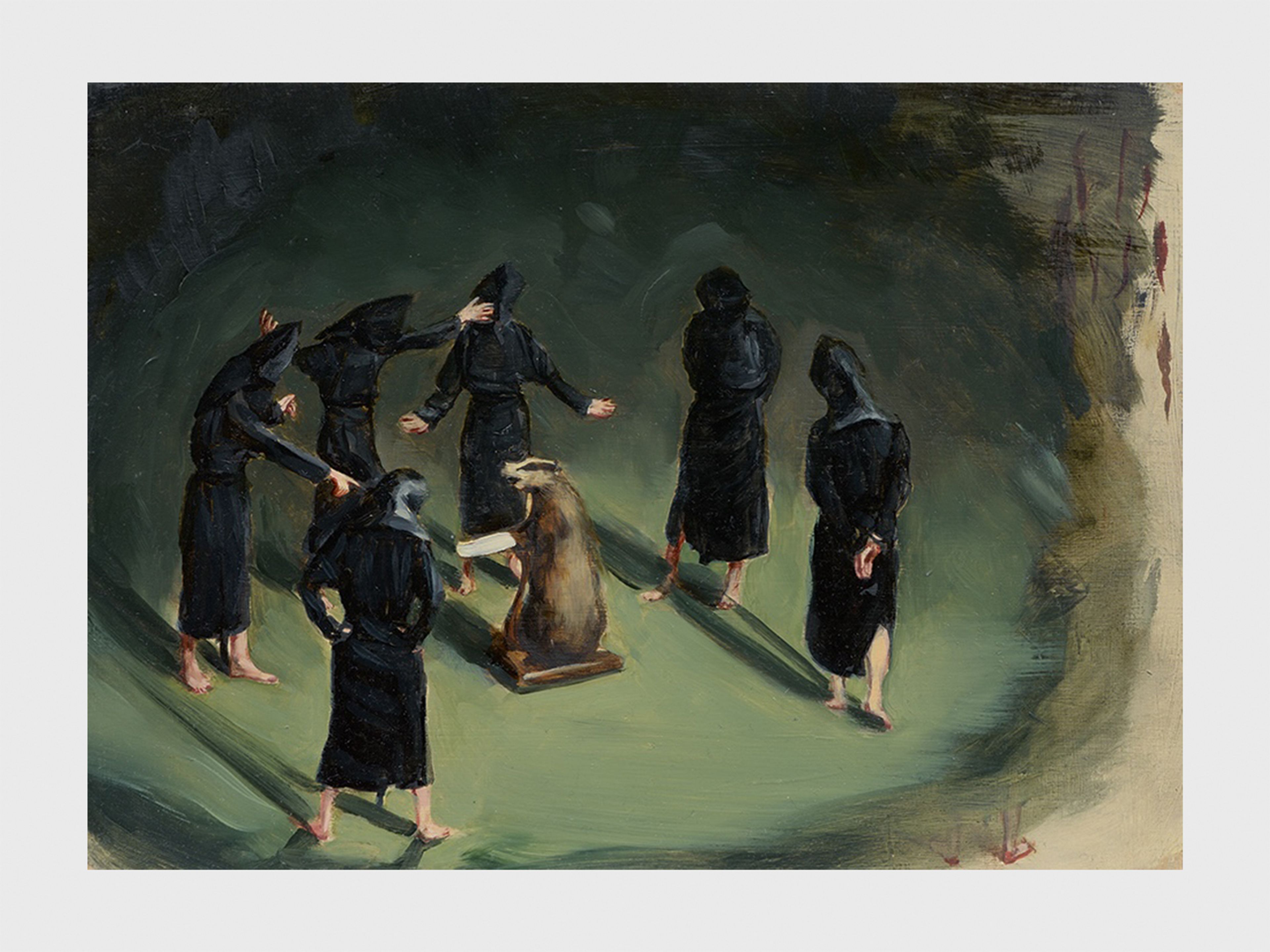

Michaël Borremans, Black Mould/The Badger's Song, 2015

“I do have a lot of baggage from art history in Western culture, but I try not to let it weigh down my work....”

“Because you want your work to be free from direct influence?” I ask.

“Because I don’t want my work to lose its sense of humor,” he answers. “I want to have a sense of flight while working. And I don’t want to think about art while making it. History, anthropology, science, and religion—anything developed by human culture—is the food.”

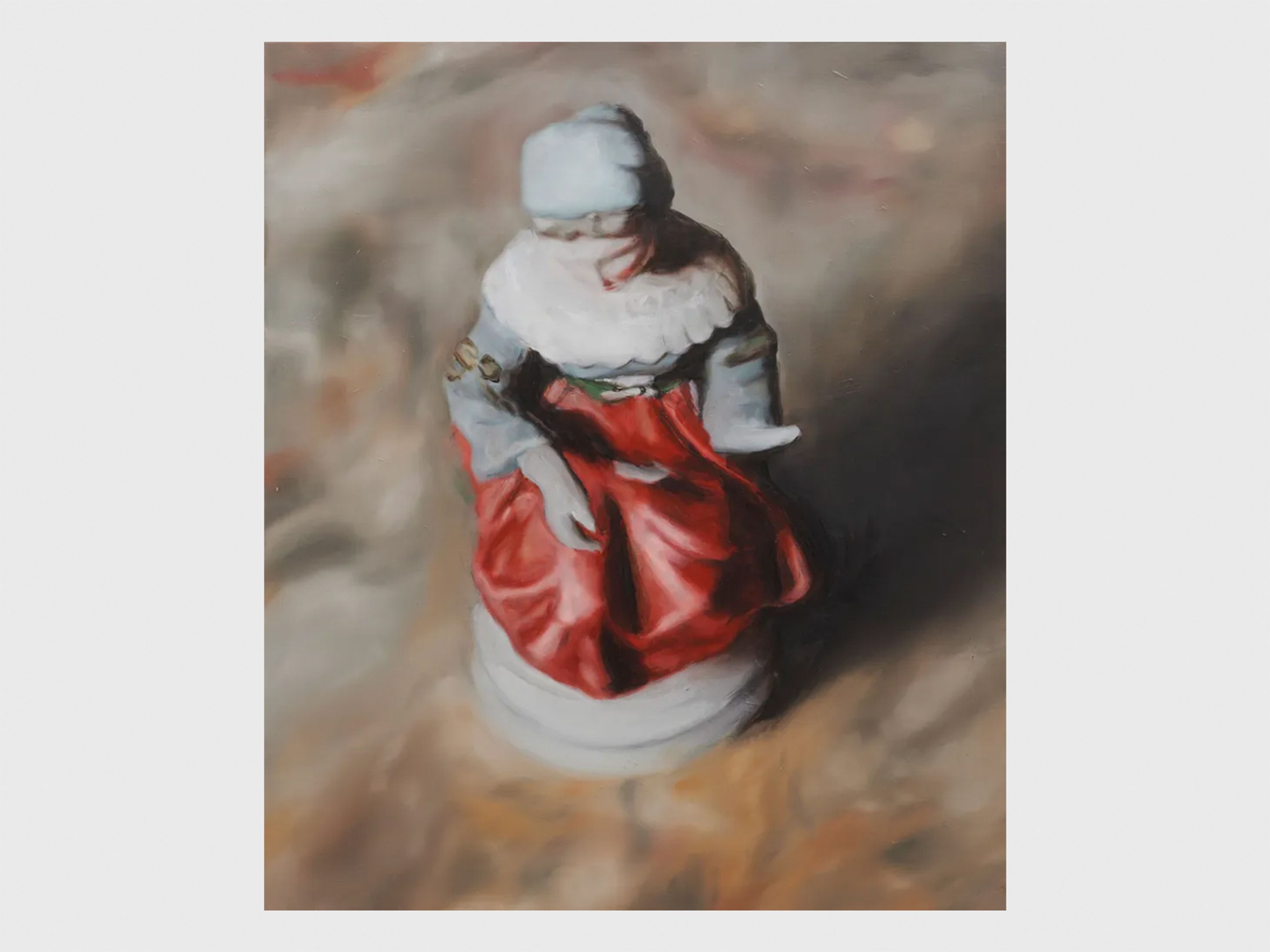

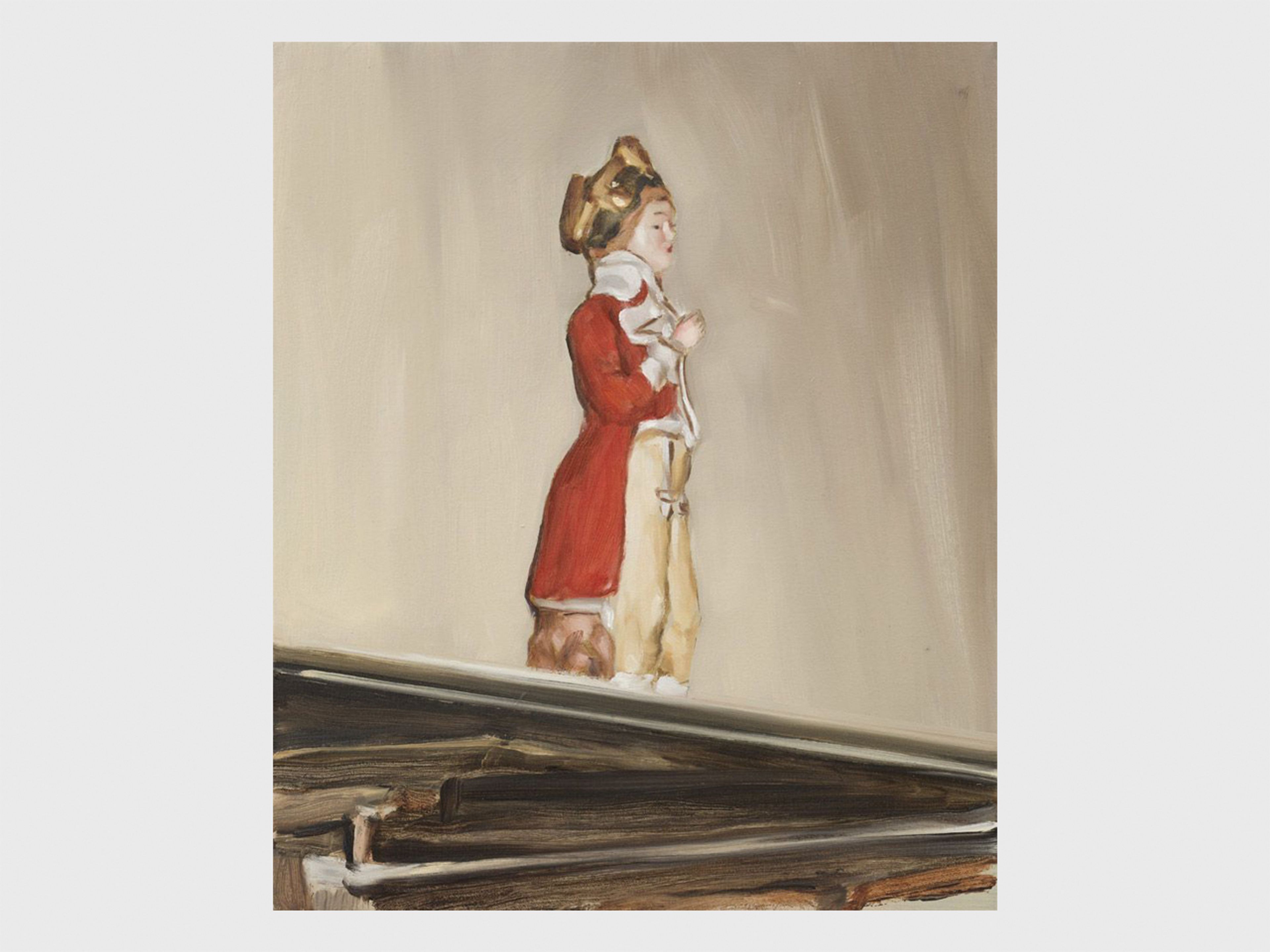

“Besides,” he says, “these antique figurines are largely influenced by rococo aesthetics”—and the figurines have appeared in his work before.... In the generic, he says, the viewer can find something universal.

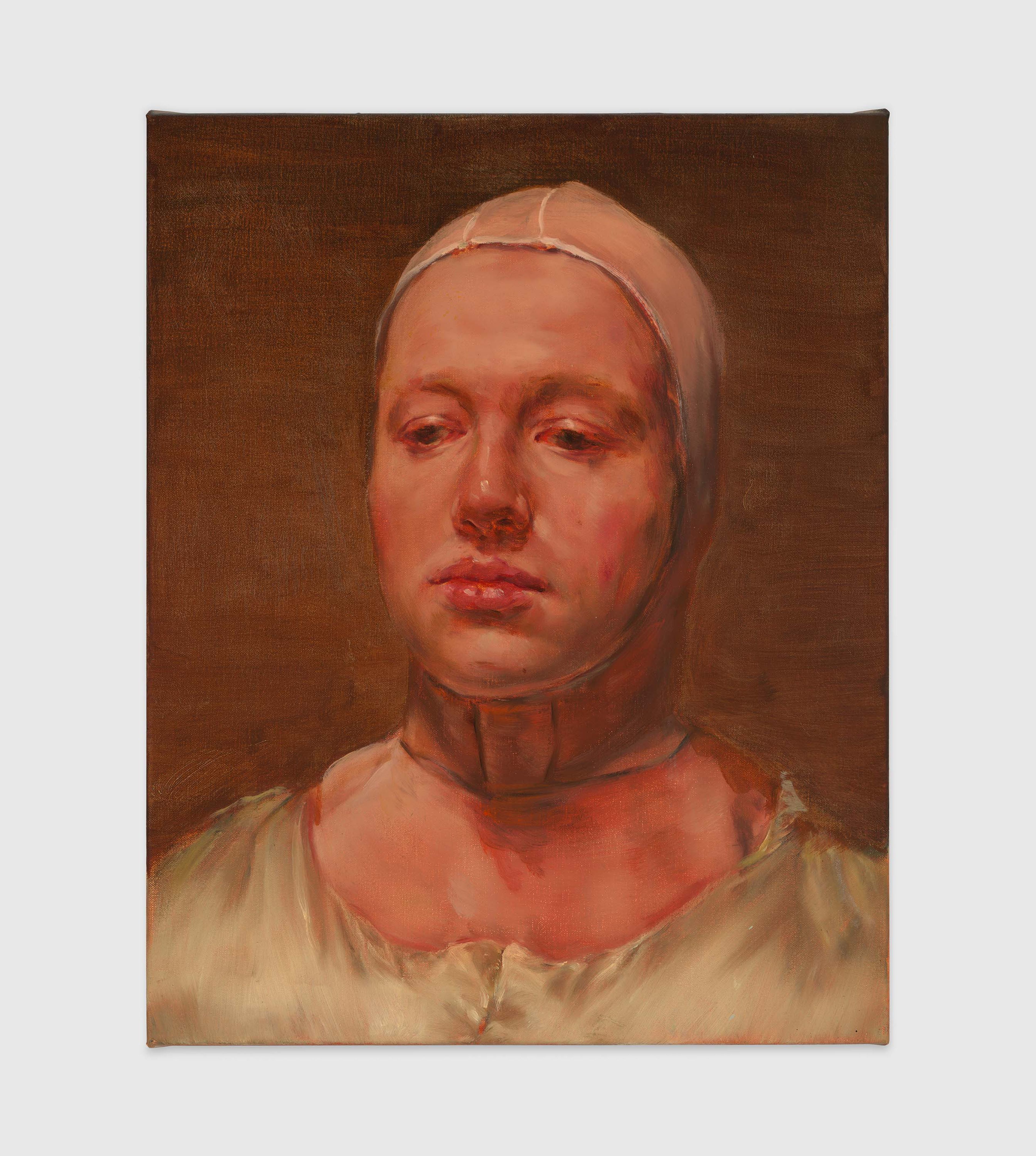

“[The romantic attitude is] one level in my work that is significant and important to me. That’s why a portrait of mine can be perceived as a landscape, because it also appeals to the subconscious. The work is never literal, it can never be perceived that way.”

—Michaël Borremans in conversation with Julian Taffel, Marfa Journal, 2024

Installation view, Michaël Borremans: The Monkey, David Zwirner, London, 2024

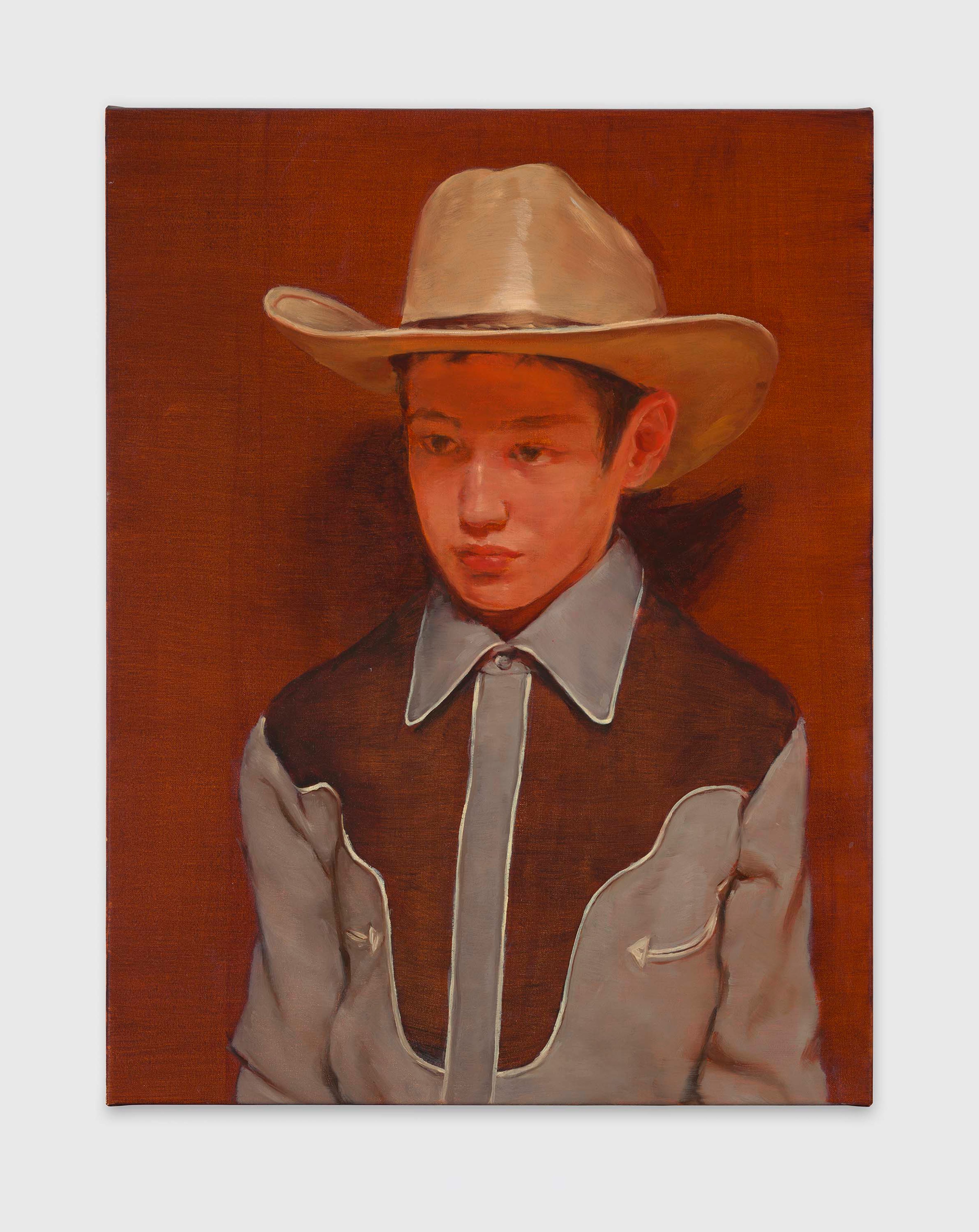

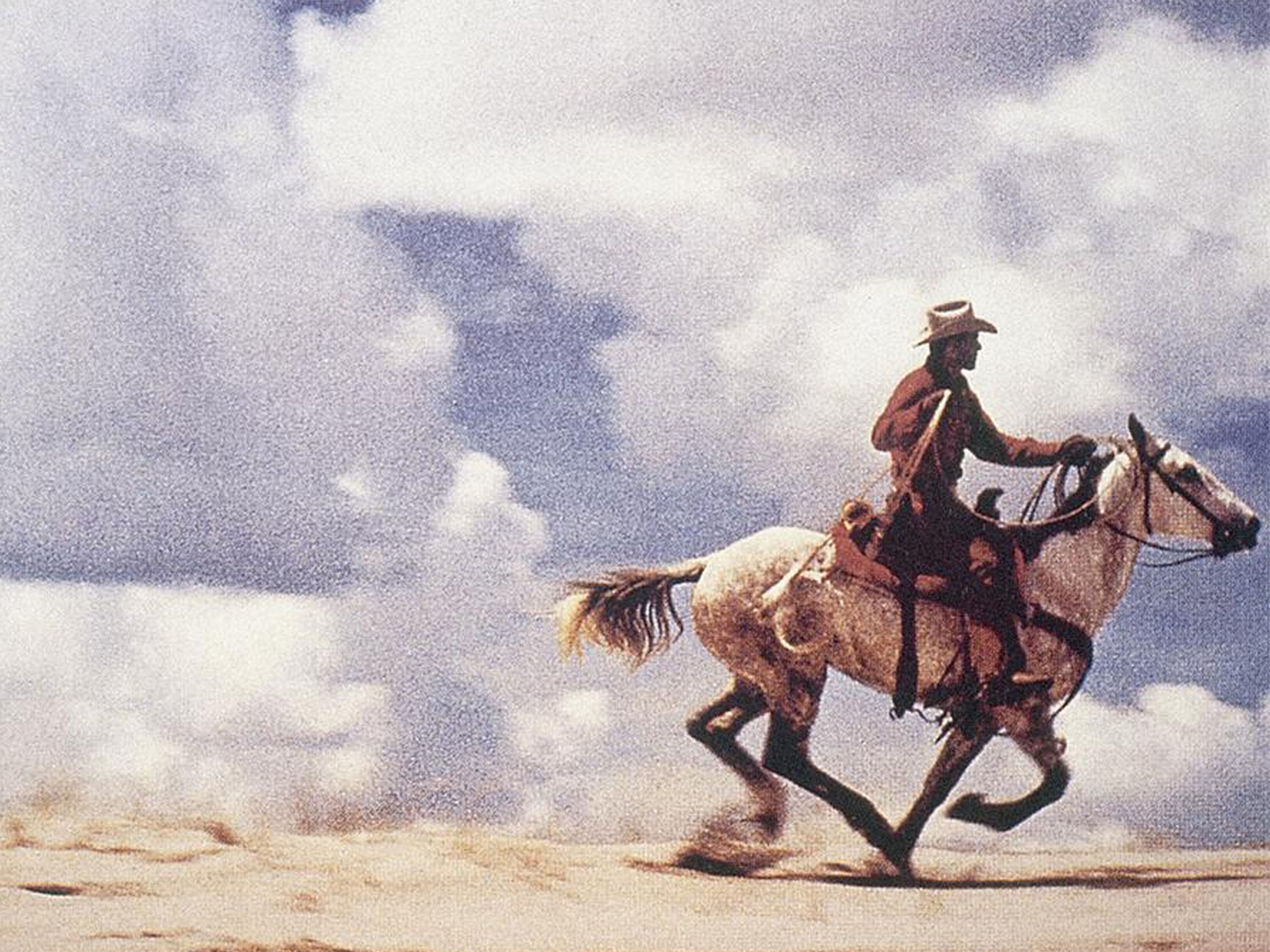

Richard Prince, Untitled (cowboy), 1989 (detail). Collection of Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Still from David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, 2001

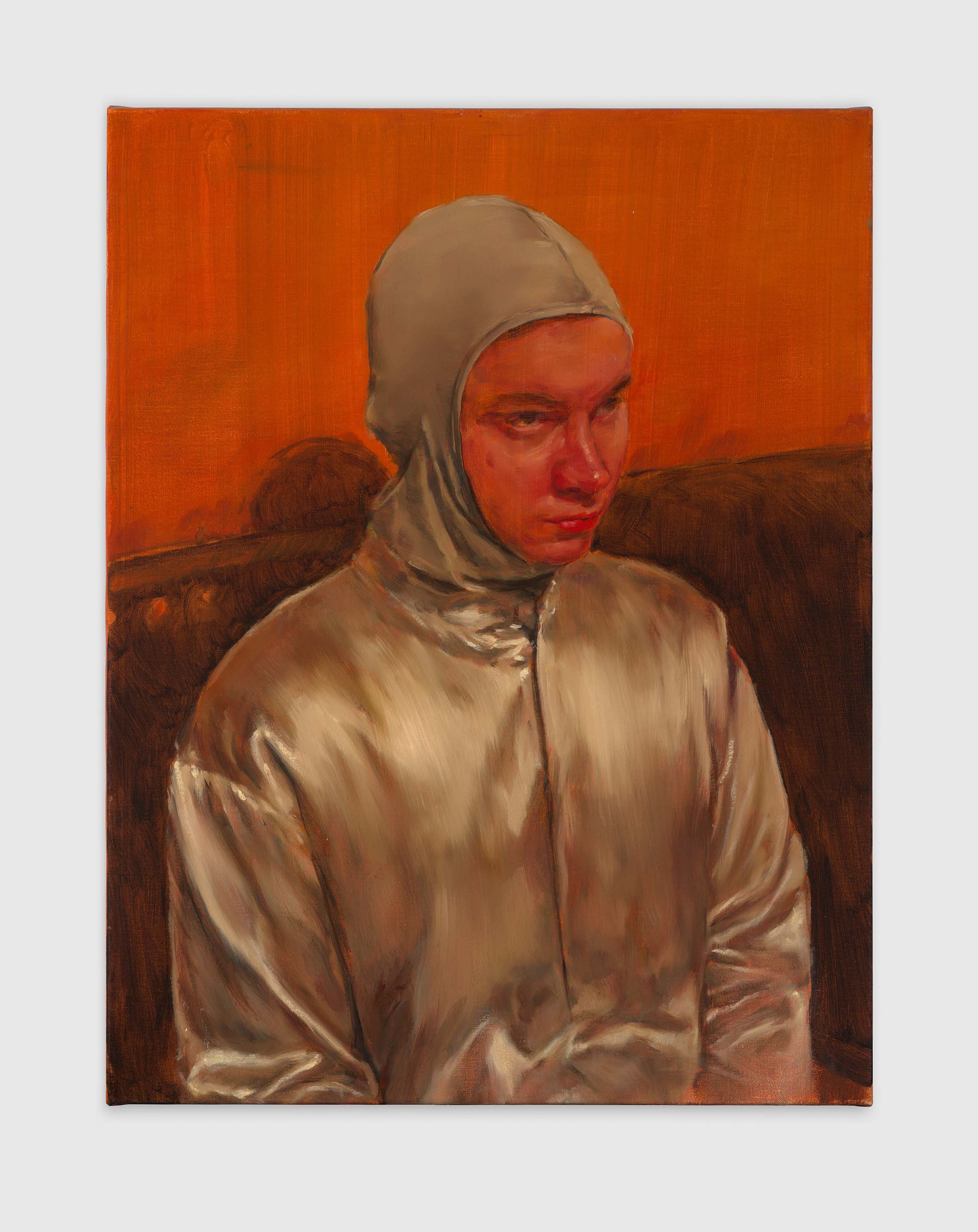

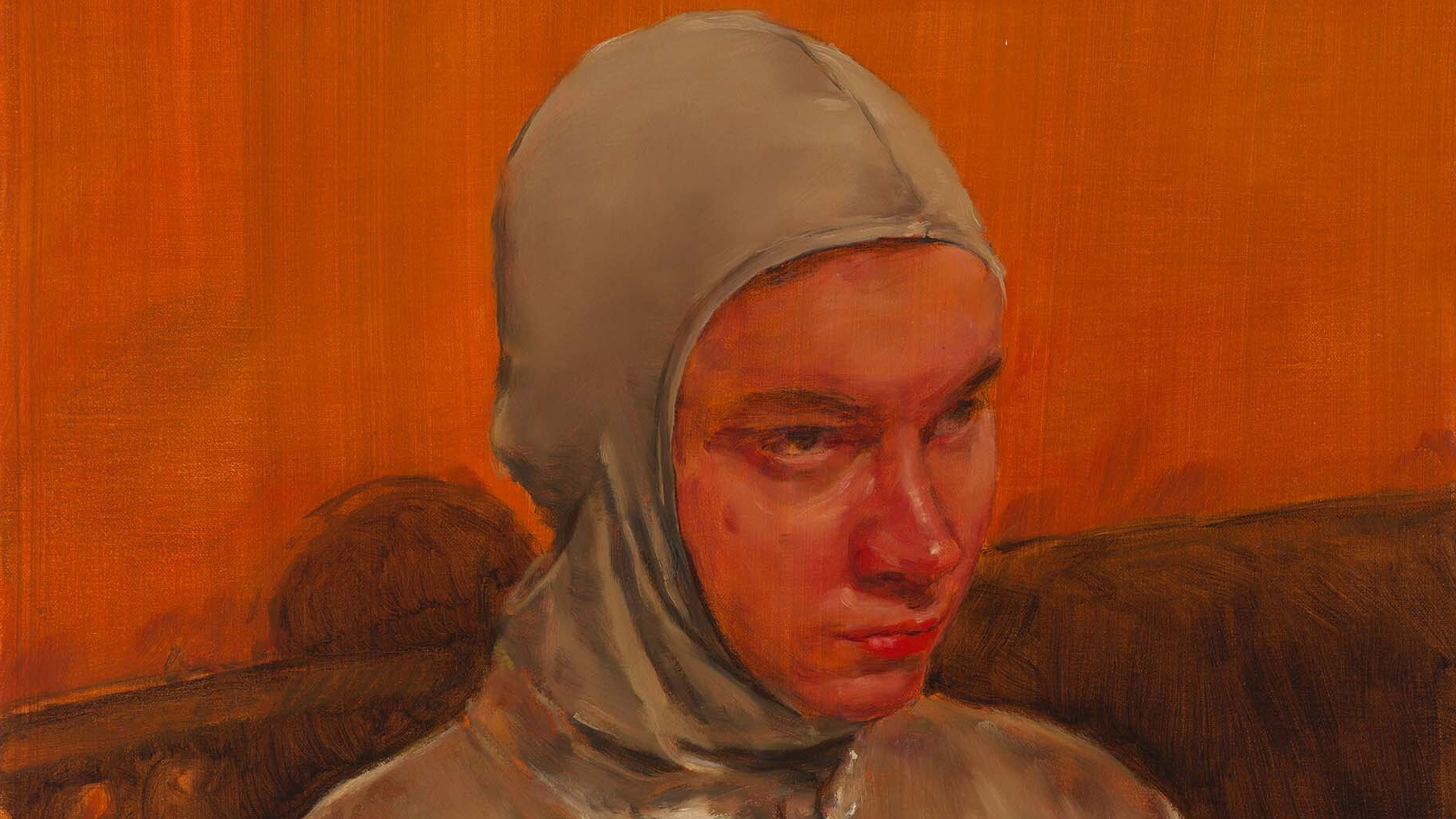

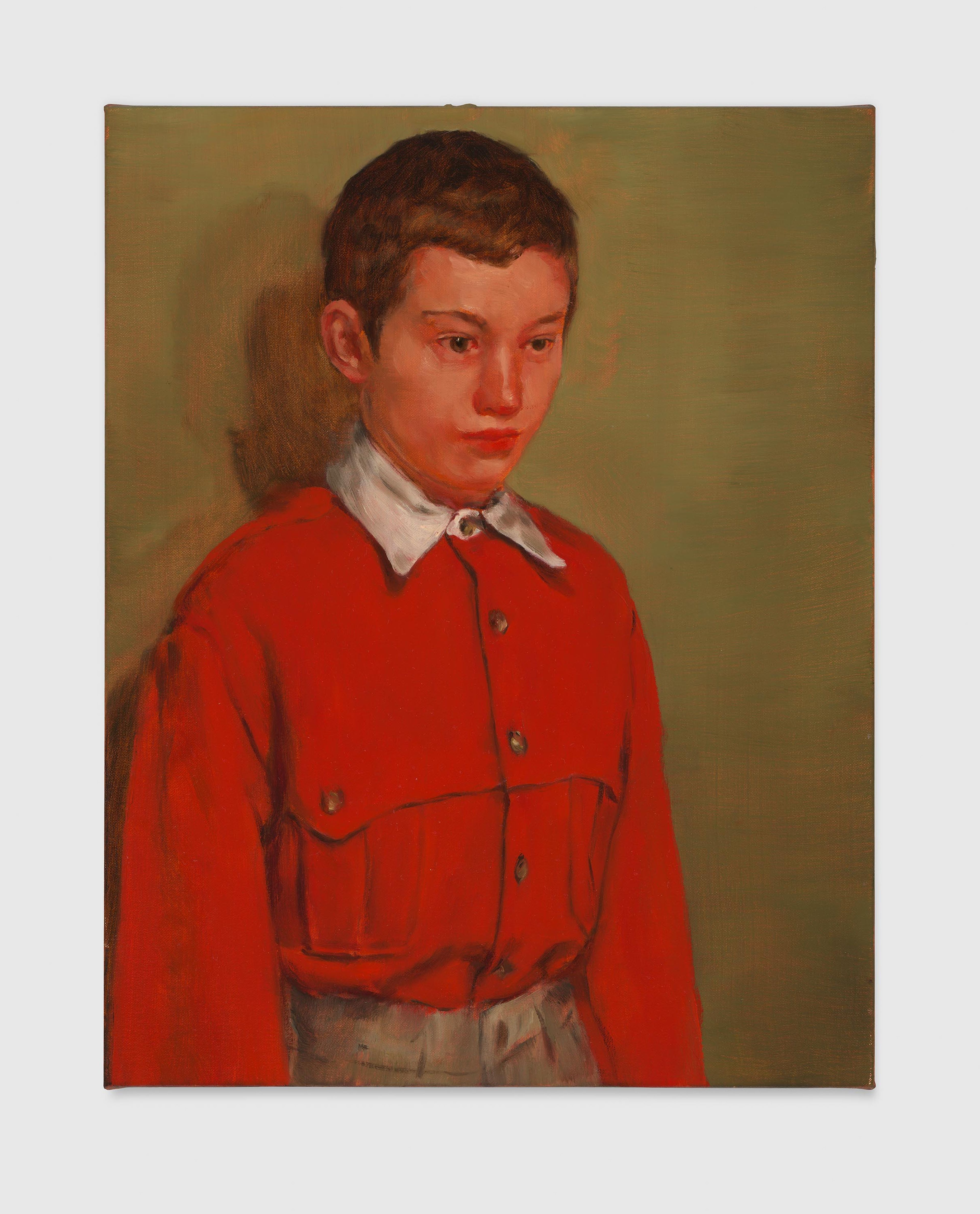

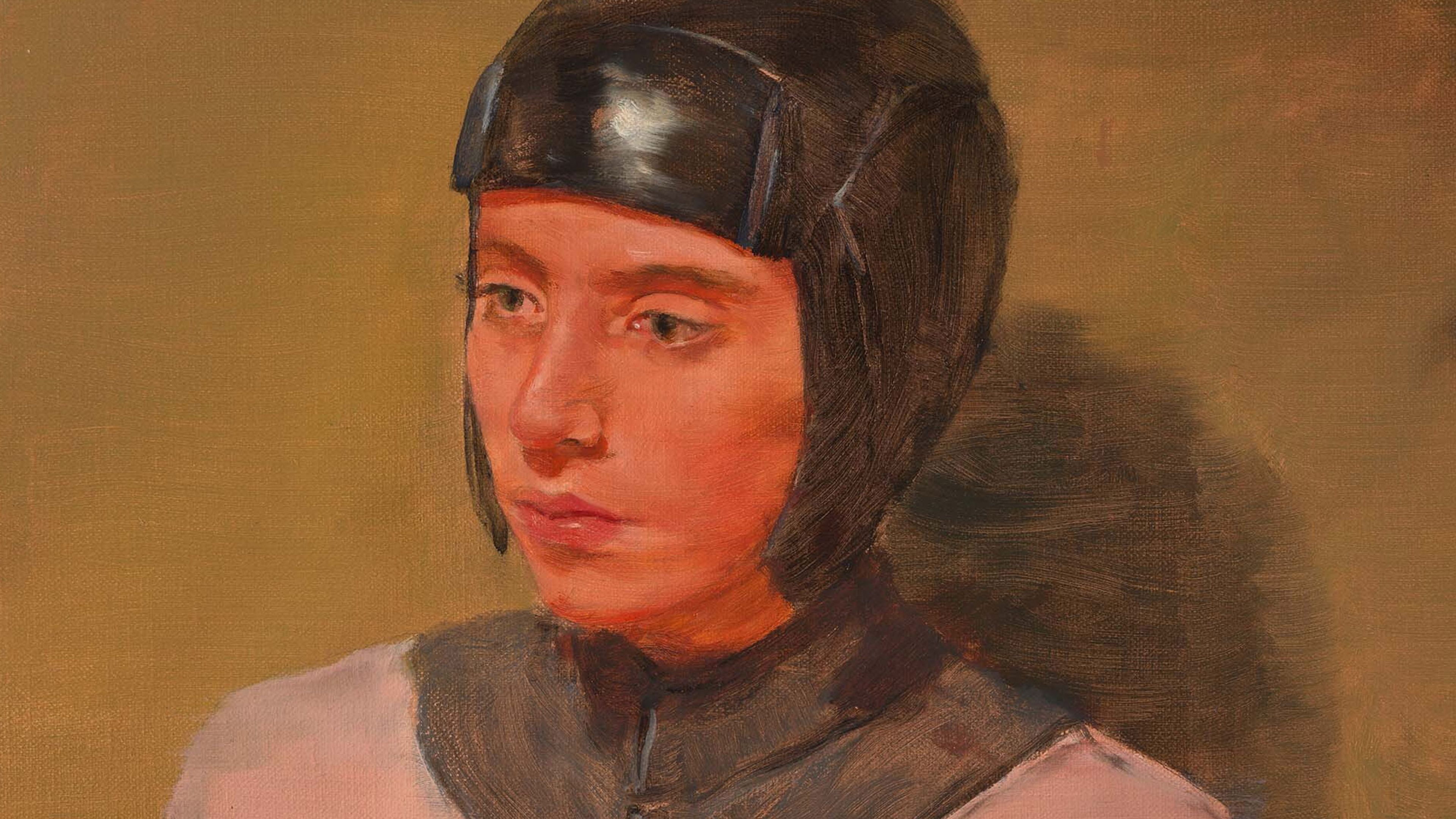

The cowboy’s costume is significant for its repeated use in storytelling, art, and film, and for the shorthand we ascribe to it. It brings numerous adjectives up the throat, not unlike acid reflux. This seems deliberate. A misdirection. Everything else about the work is deliberate, after all: the technical approach, which is measured and precise; the controlled and static subject; even the setting, or absence of one. The cowboy appears site-specific to a box or a dark room, and not at all free to roam.

The work is an open target for the symbolism we hurl at it. Go ahead, the painting taunts: Say this is a work about childhood, machismo, the individual, or memory. Perhaps say something that sounds familiar, quote someone, use a found sentence, or draw on a personal flashback. Try to say something of value. Say it without repetition or cliché. Say something we haven’t heard before.

Michaël Borremans, The Talent, 2023 (detail)

“I play with the conventions of painting as a medium and the conventions of imagery in Western culture. I question it by making unexpected associations within the image, which are very subtle sometimes, and that provokes an interesting situation in how you perceive the work.”

—Michaël Borremans

Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656 (detail). Collection of Museo del Prado, Madrid

Édouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882. Collection of Courtauld Gallery, London

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait of Lucian Freud, 1964 (detail). Private collection

Stepping back from The Monkey series for just a moment, let’s scan the vast conversation and criticism Borremans’s oeuvre has generated over the past two decades. A survey of writing about Borremans’s work turns up refrains and their immediate rebuttals. There is great veneration for his labor-intensive technique and for the weight of his paintings. But Borremans is also known for levity. He paints as if exasperated by the existence of gravity. He has great compassion for the sacred and liturgical, for the uncanny, for Velázquez’s light and drama ... for Manet’s briskness and emotion ... and for Francis Bacon’s interiority. He holds equal affinity for the punch line and the non sequitur, for the profane and the unholy. Borremans transcends any one way of painting or being.

David Zwirner Books

Michaël Borremans: The Monkey

Interested in works by Michaël Borremans?