On Kawara: Early Works

Installation view, On Kawara: Early Works, David Zwirner, Paris, 2024

Past

November 23, 2024—January 25, 2025

Opening Reception

Saturday, November 23, 6–8 PM

Opening Reception

Saturday, November 23, 6–8 PM

Location

Paris

108, rue Vieille du Temple

75003 Paris

Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat: 11 AM-7 PM

Artist

Explore

“I did not share the nostalgia that middle-aged cohorts had for the past. Instead, I was filled with a desperate desire to tear things apart.”

—On Kawara, 1956

Installation view, On Kawara: Early Works, David Zwirner, Paris, 2024

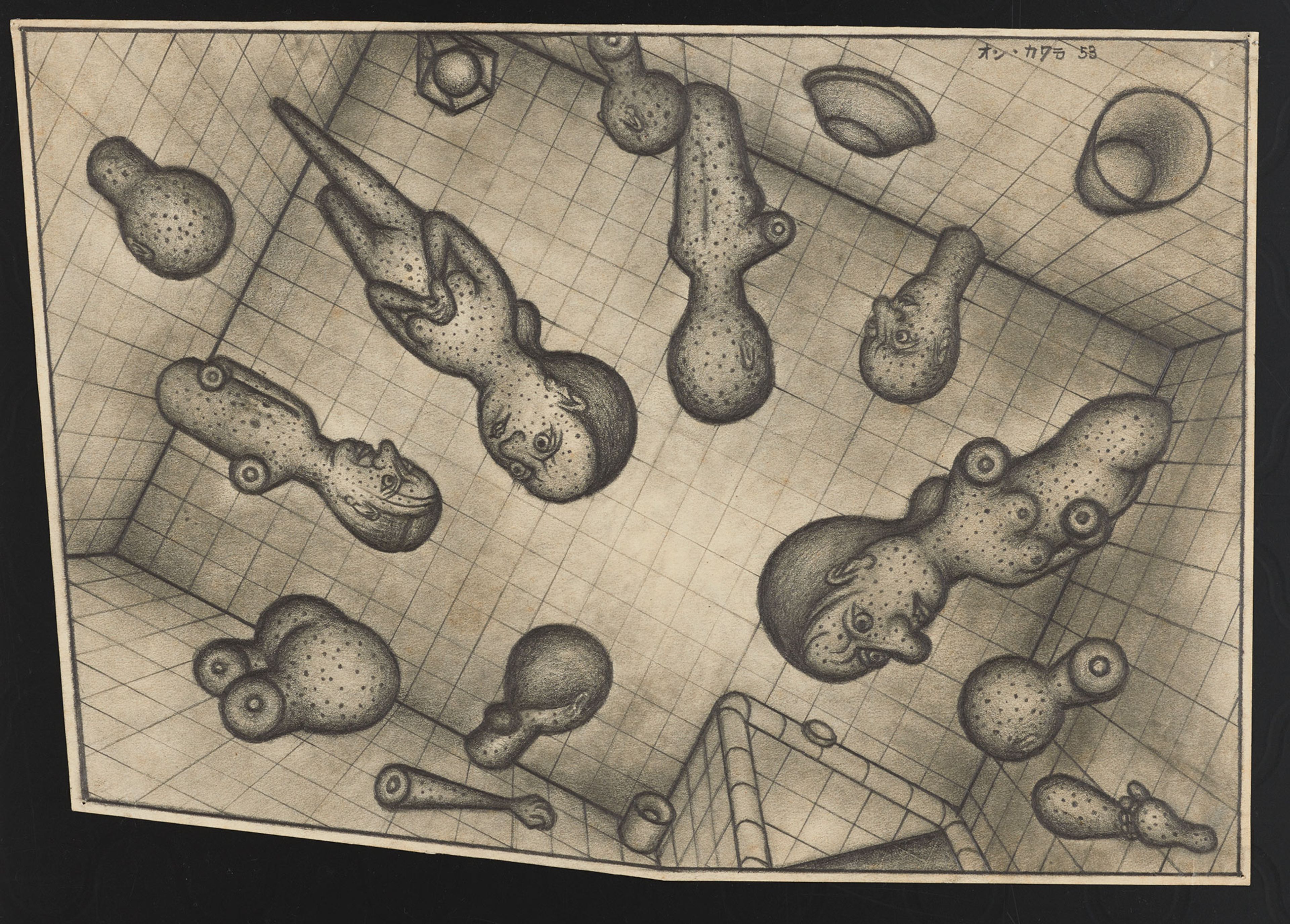

Bathroom 15, 1953. The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. © One Million Years Foundation. Photo: MOMAT/DNPartcom

Events in a Warehouse 3, 1953. The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. © One Million Years Foundation. Photo: MOMAT/DNPartcom

In 1955, On Kawara took an important step in his work by adopting the irregular outlines of his large format drawings for his paintings as well. He had already made use of this formal syntax in the two cycles of drawings entitled The Bathroom (1953–1954) and Events in a Warehouse (1954). With stretchers and canvas, he created his first polygonal pictures, which rank amongst the earliest of postwar shaped-canvas paintings. American examples can be found around 1960 in the works of Frank Stella.

Installation view, On Kawara: Early Works, David Zwirner, Paris, 2024

“The symmetrical structure of the picture plane is too weak to express the absurdity and desperate anxiety of today's society, where we ourselves are split in the midst of our social mechanism and its tremendous energy of materials. Symmetrical space is based on the absoluteness of vision and, therefore, it cannot grasp the radical conflicts and echoes of disharmony between humanity and bloodless matters.... We should set up multi-focused canvases so that the action and reaction among the foci will produce a structural power that strongly invites the viewer into the painterly space.”

—On Kawara, 1956

Golden Home, 1956 (detail)

“As in Franz Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis,’ both these items of furniture seem to present a barrier of insurmountable height.... Motif, space and irregular edges seem to be tottering. There is something threatening about this golden home populated by vermin.”

—Mario Kramer, curator and writer, 1994

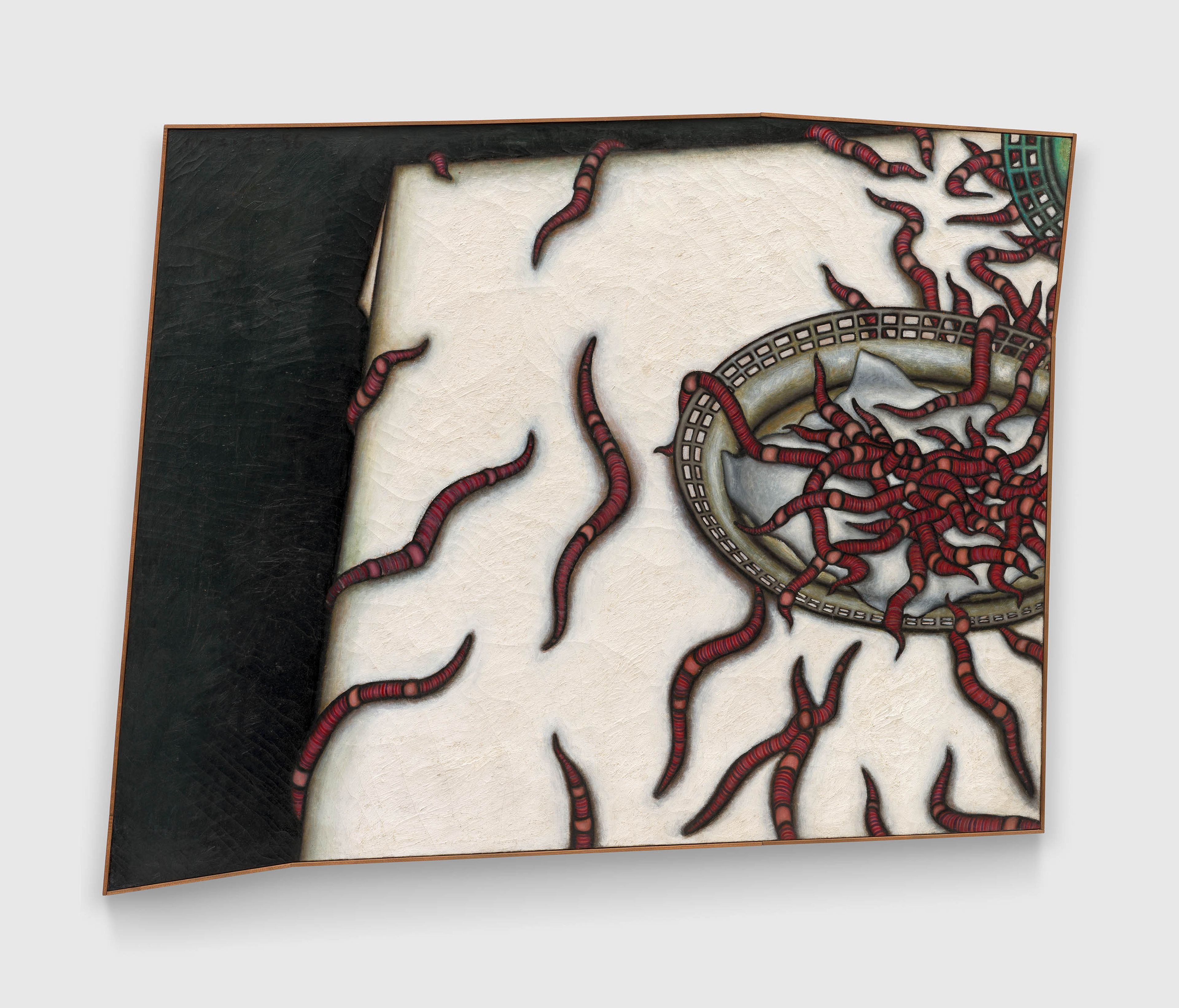

Untitled, 1956 (detail)

“On Kawara has created an almost classic still-life. The worm, the lowest form of life, arouses only feelings of horror and disgust. Here, it is a vanitas symbol indicating the transience of human existence. At the left-hand edge of the picture yawns a deep, black abyss, emphasized by the sharply angled lower corner of the painting.”

—Mario Kramer, curator and writer, 1994

Installation view, On Kawara 1952-1956 Tokyo, Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK), Frankfurt, 1994

Installation view, On Kawara 1952-1956 Tokyo, Museum für Moderne Kunst (MMK), Frankfurt, 1994

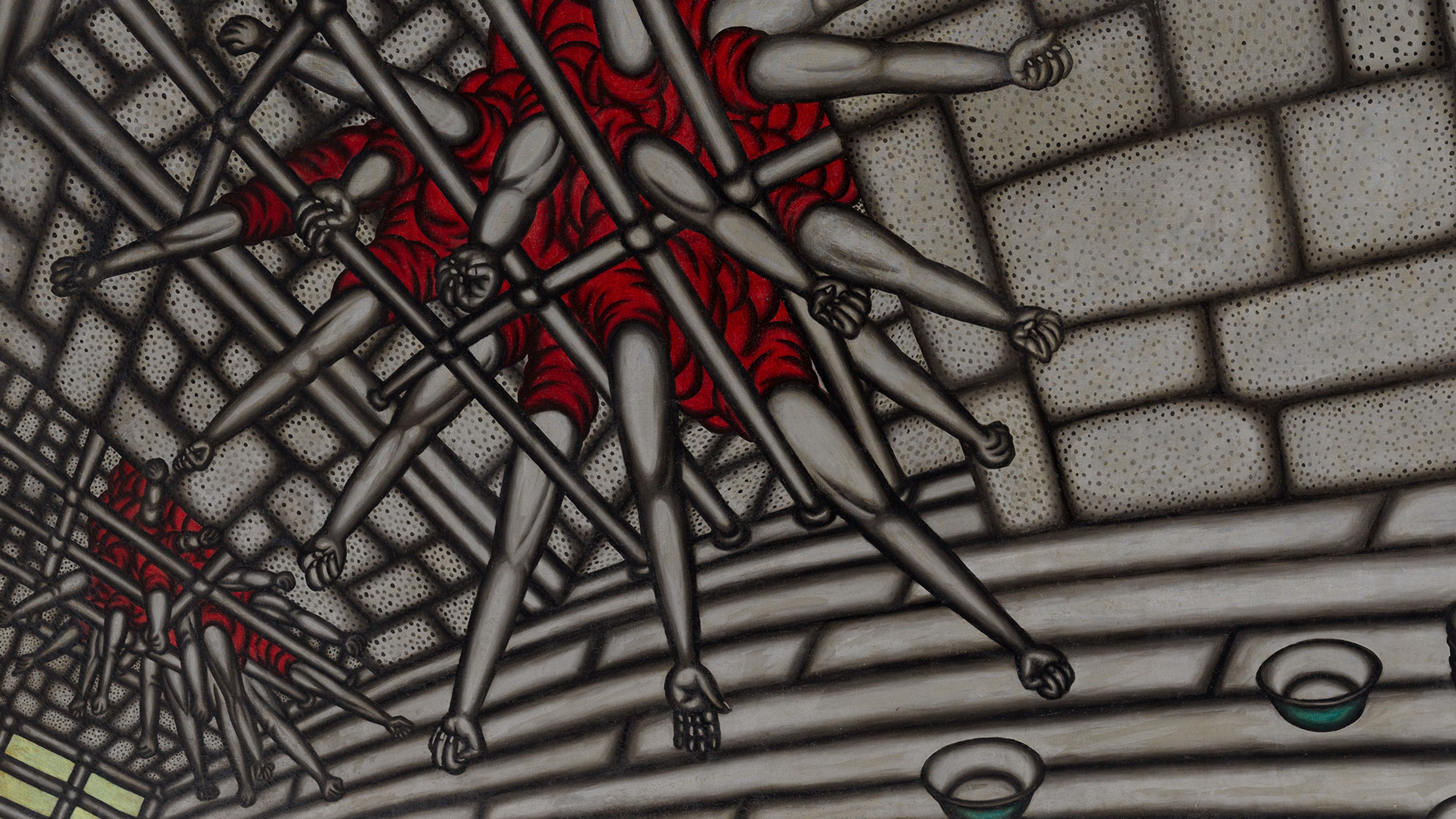

Absentees, 1956 (detail)

“Absentees ... depicts robotic figures, inhabitants of unyielding and enclosed built environments, subjected to unspecified malevolence. In Absentees they are literally incarcerated. The appearance of their straight strong arms through barred openings constitutes a rare gesture of defiance, but speaks essentially of hopelessness.”

—Jonathan Watkins, curator and writer, 2002

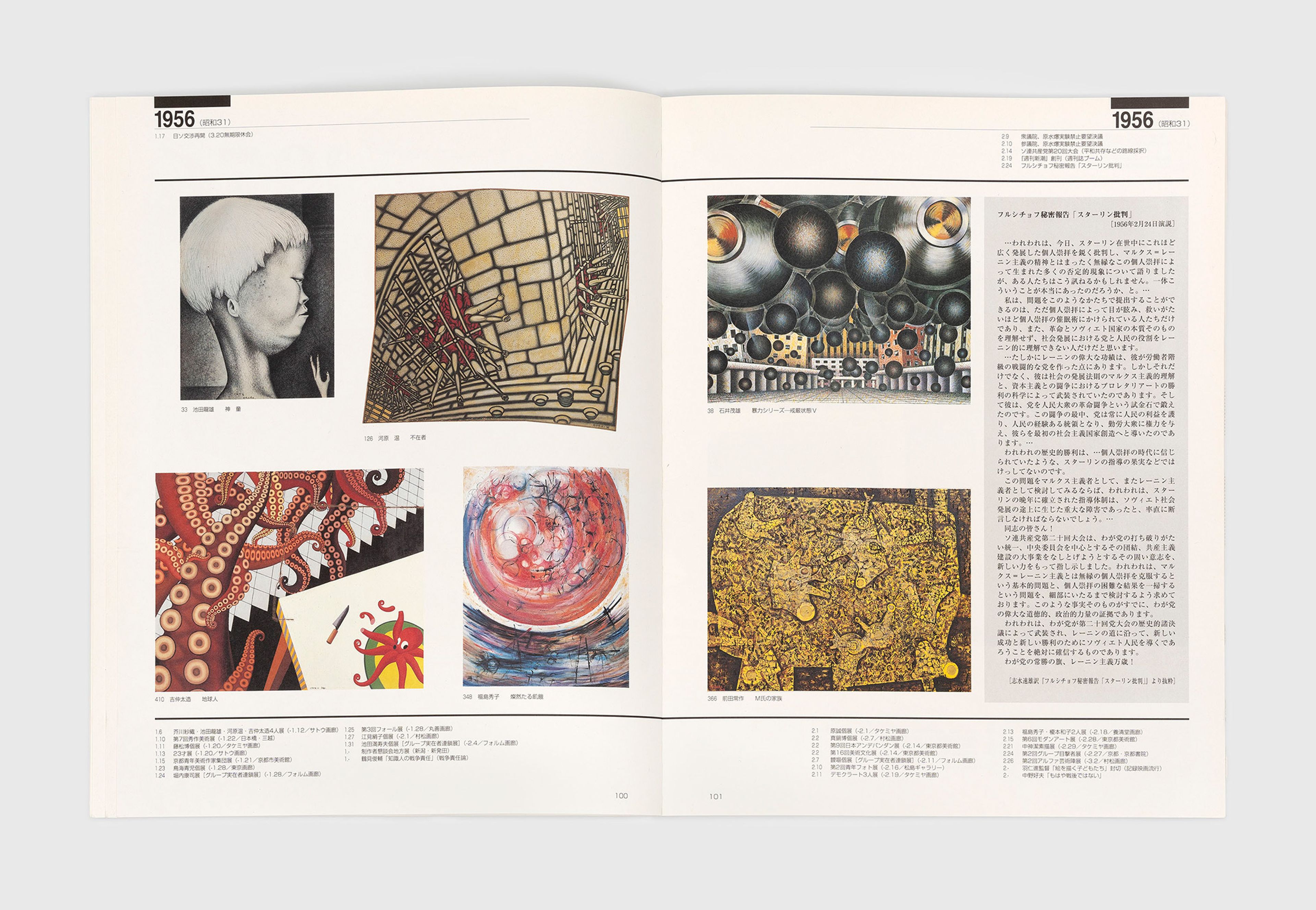

Spread from the 1998 Nagoya Museum catalogue for Realism in Postwar Japan 1945–1960

Installation view, Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2012. Photo by Thomas Griesel. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Absentees was included in the exhibition Realism in Postwar Japan 1945–1960 at Nagoya Museum in 1998, along with other early paintings by On Kawara. Stones Thrown (1956) was included in the exhibition Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 2012.

Driftwood advancing on Daifuku village, Fukuoka, following the Northern Kyushu flood, 1953

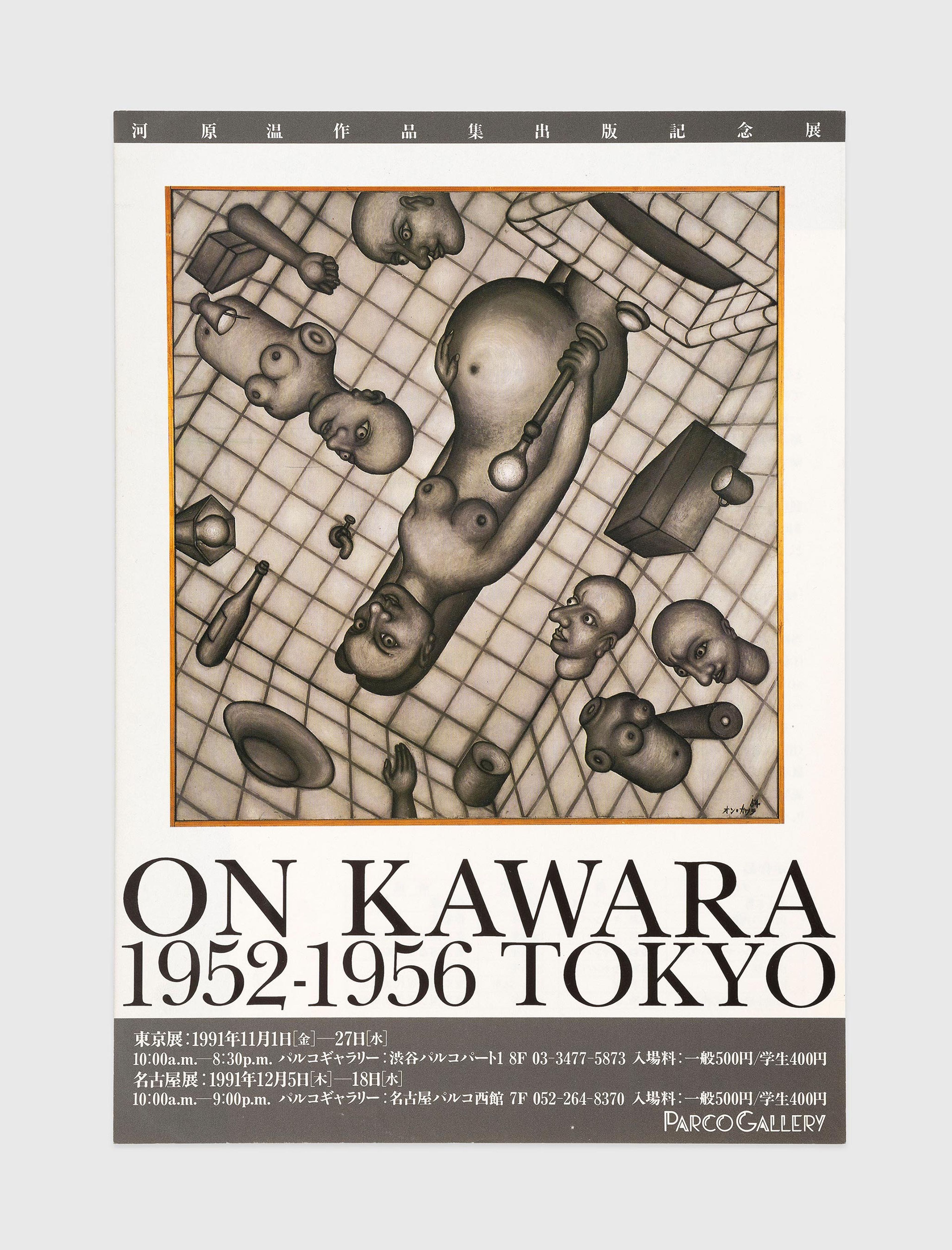

Flood was included in the exhibition On Kawara: 1952–1956 along with other early paintings and works on paper at Parco Gallery, Tokyo, in 1991.

“I believe intensity of form is significantly augmented and made more complex by the fierce interaction—attraction and repulsion—among multiple focuses. These focuses are not necessarily confined within the canvas but, like the orthocenter of an obtuse triangle, converge upon each other with a terrific force.”

—On Kawara, 1956

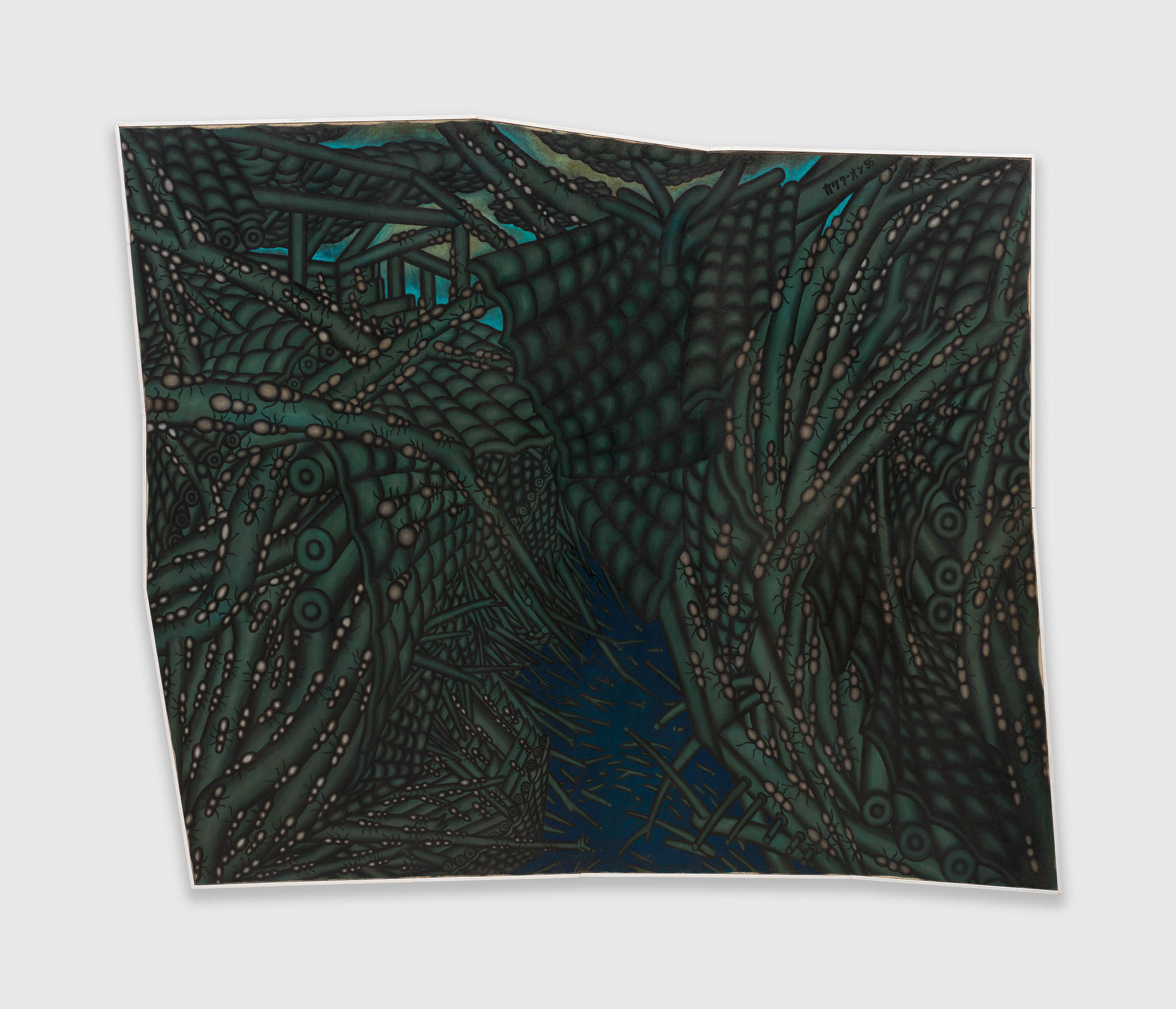

Flood, 1955 (detail)

“The large painting Flood (1955) leads us into a microcosm of nature…. Even the observer becomes a tiny ant, seeking a path through the dark and shadowy undergrowth. There is a constant to and fro in the endless cycle of nature…. The plantlike structures create archaic architectural forms which seem to have been built by human hands. The ant becomes the embodiment of the human being and is merely a busy worker devoid of all individuality. Society is shown here as a mass movement, serving only to march in an army.”

—Mario Kramer, curator and writer, 1994

Installation view, On Kawara: Early Works, David Zwirner, Paris, 2024

On Kawara: Date Paintings