Exhibition

William Eggleston: The Last Dyes

Want to know more?

Past

November 16, 2024—February 1, 2025

Opening Reception

Saturday, November 16, 6–8 PM

Location

Los Angeles

606 N Western Avenue

Los Angeles, CA 90004

Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat: 10 AM-6 PM

Artist

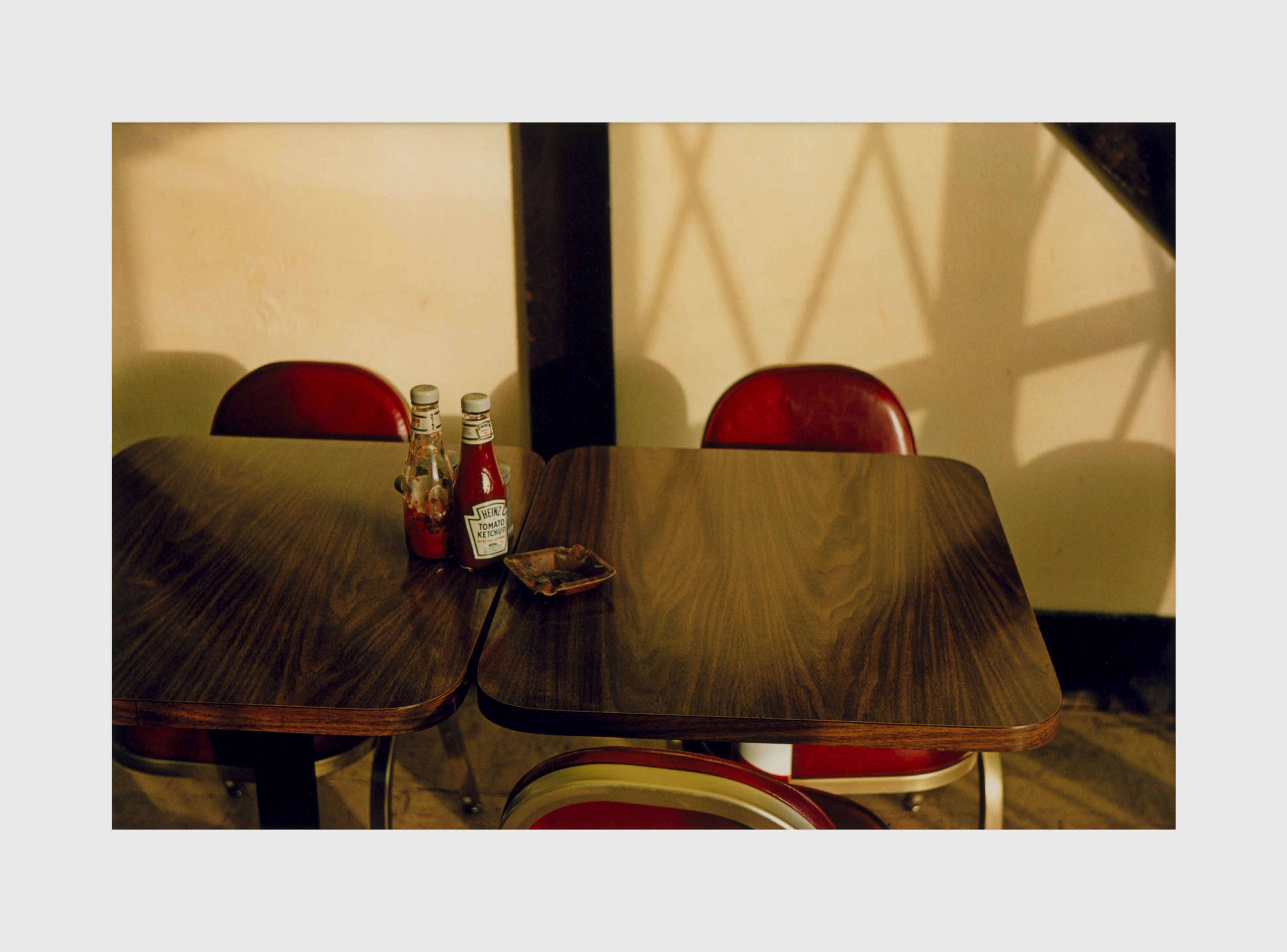

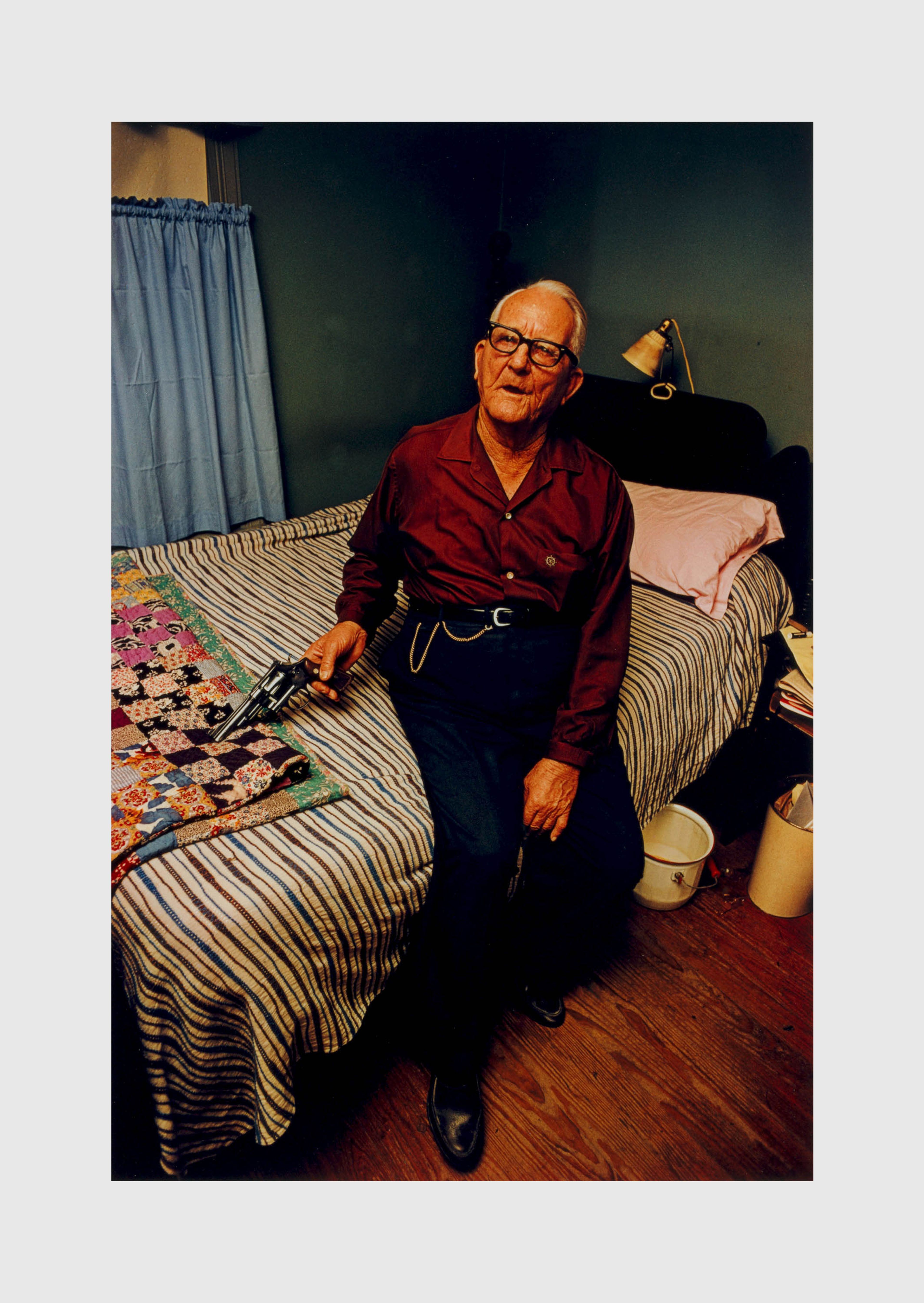

William Eggleston, Untitled, 1972

Explore

William Eggleston: The Last Dyes

Behind the scenes of William Eggleston: The Last Dyes, featuring Eggleston and dye-transfer specialists Guy Stricherz and Irene Malli

“I was reading the price list of this lab in Chicago and it advertised ‘from the cheapest to the ultimate print’. The ultimate print was a dye-transfer.... The color saturation and the quality of the ink was overwhelming. I couldn't wait to see what a plain Eggleston picture would look like with the same process. Every photograph I subsequently printed with the process seemed ... better than the previous one.”

—William Eggleston in conversation with editor and writer Mark Holborn, 1991

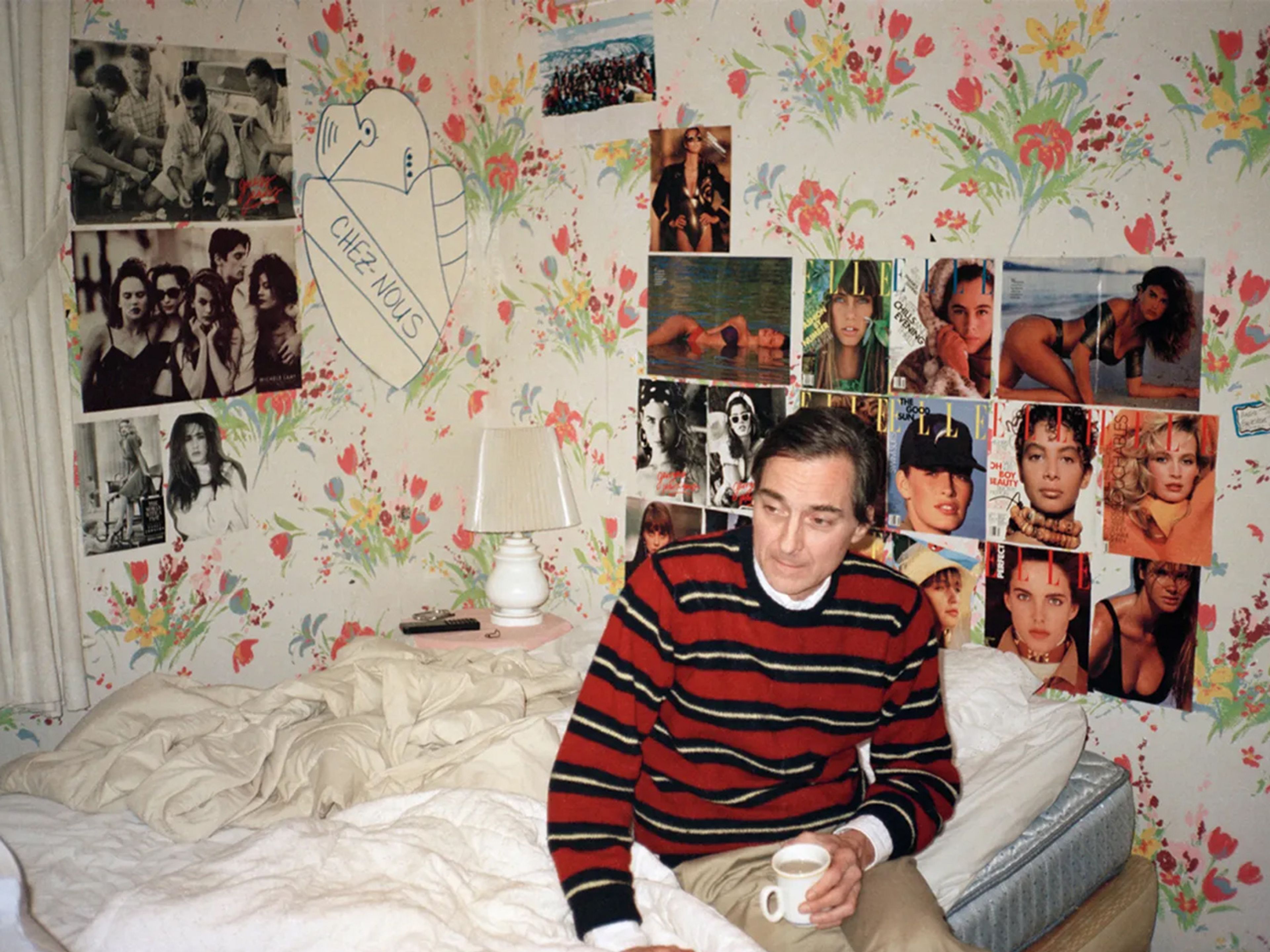

William Eggleston at his studio in Memphis

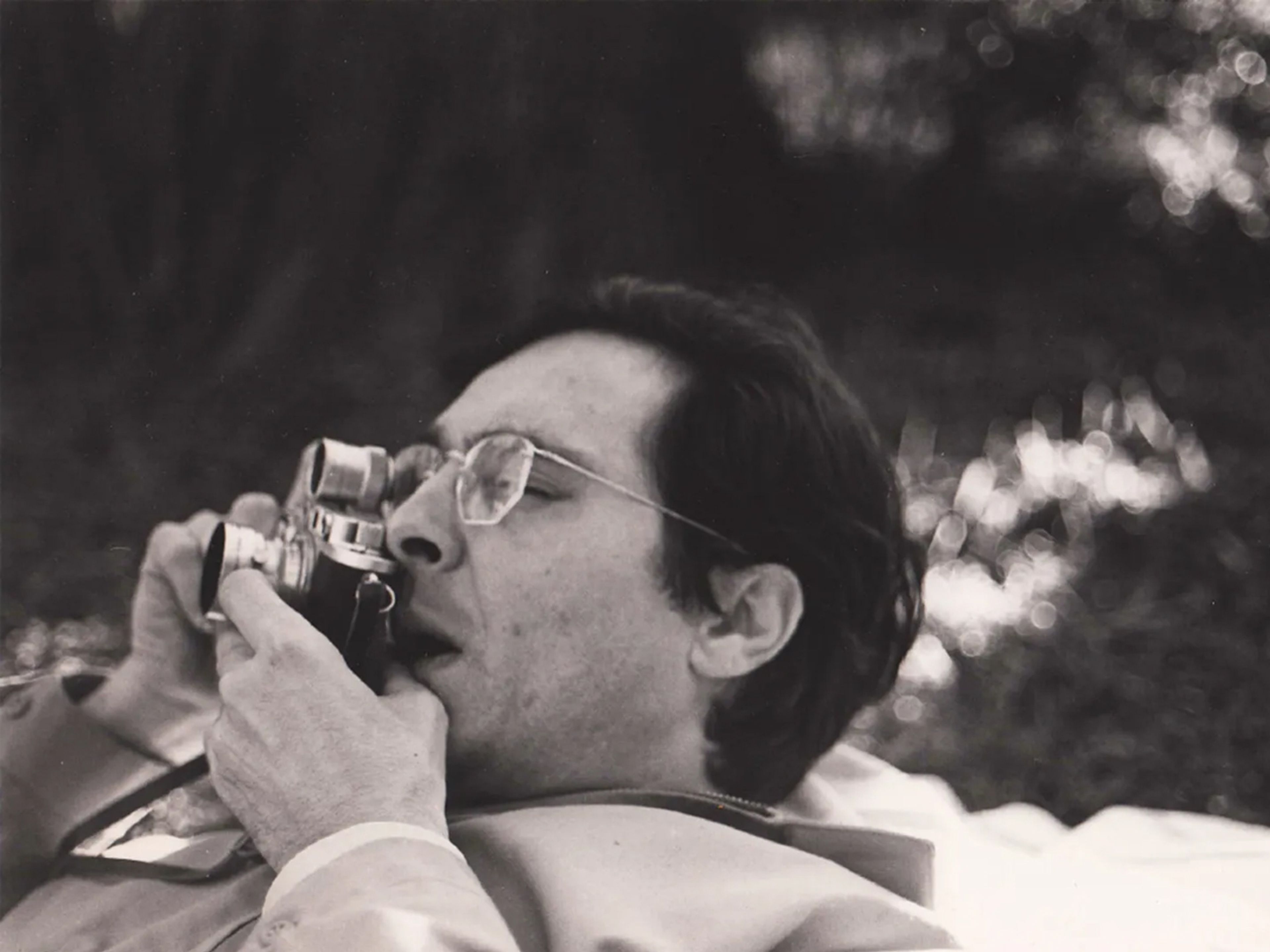

William Eggleston. Photo by Langdon Clay

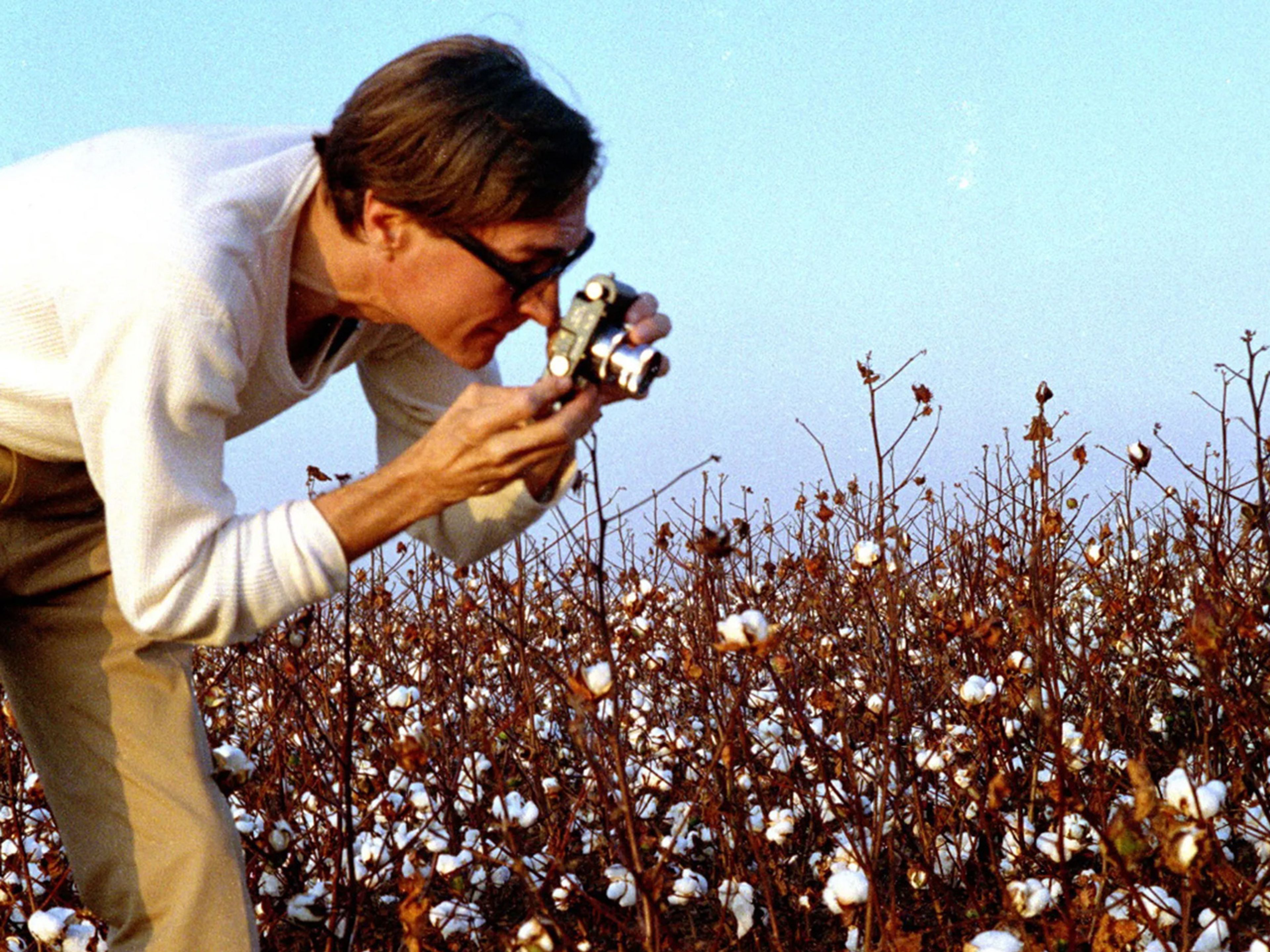

William Eggleston. Photo by Maude Schuyler Clay

William Eggleston. Photo by Winston Eggleston and William Eggleston III

William Eggleston. Photo by Stanley Booth

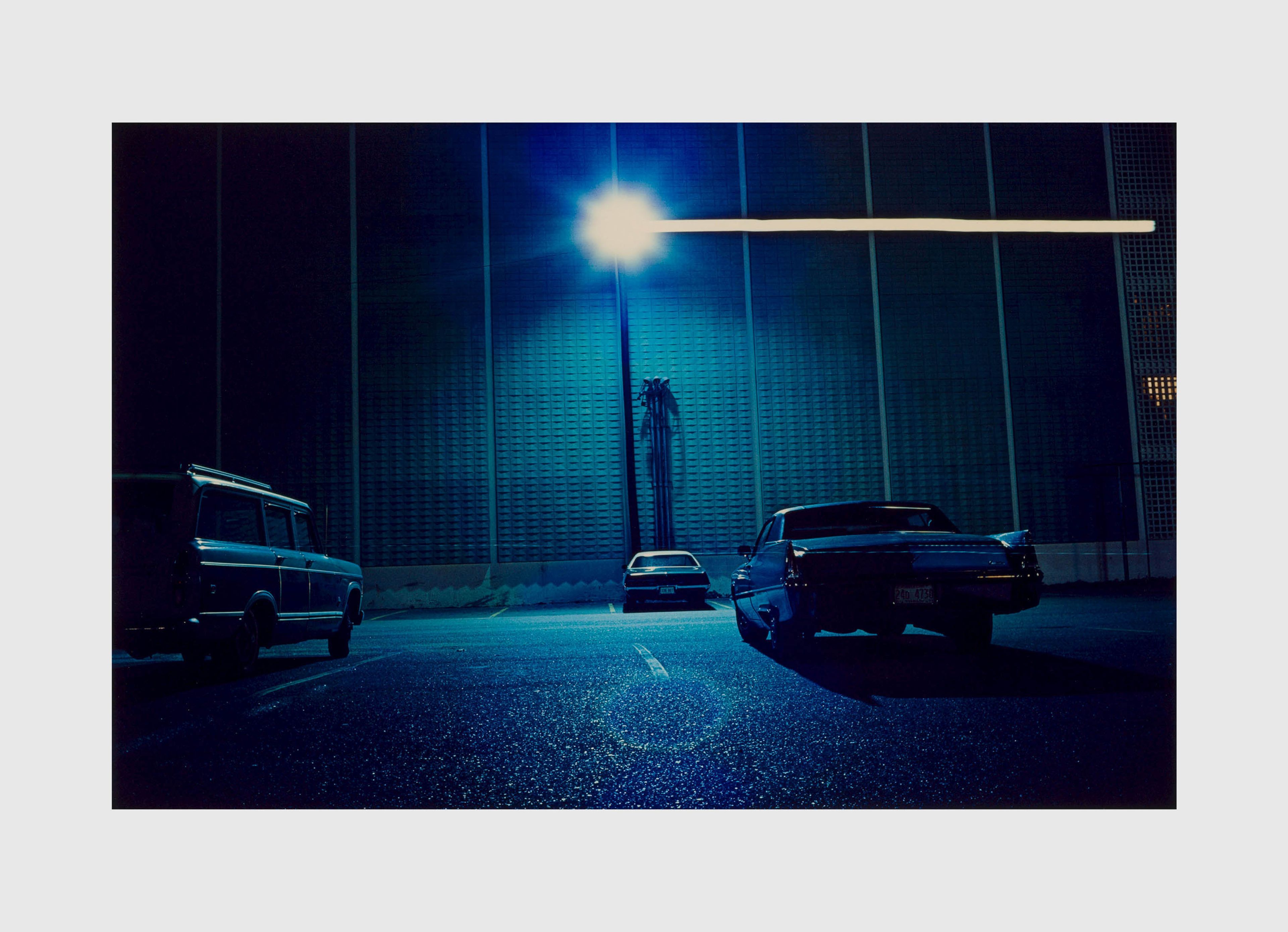

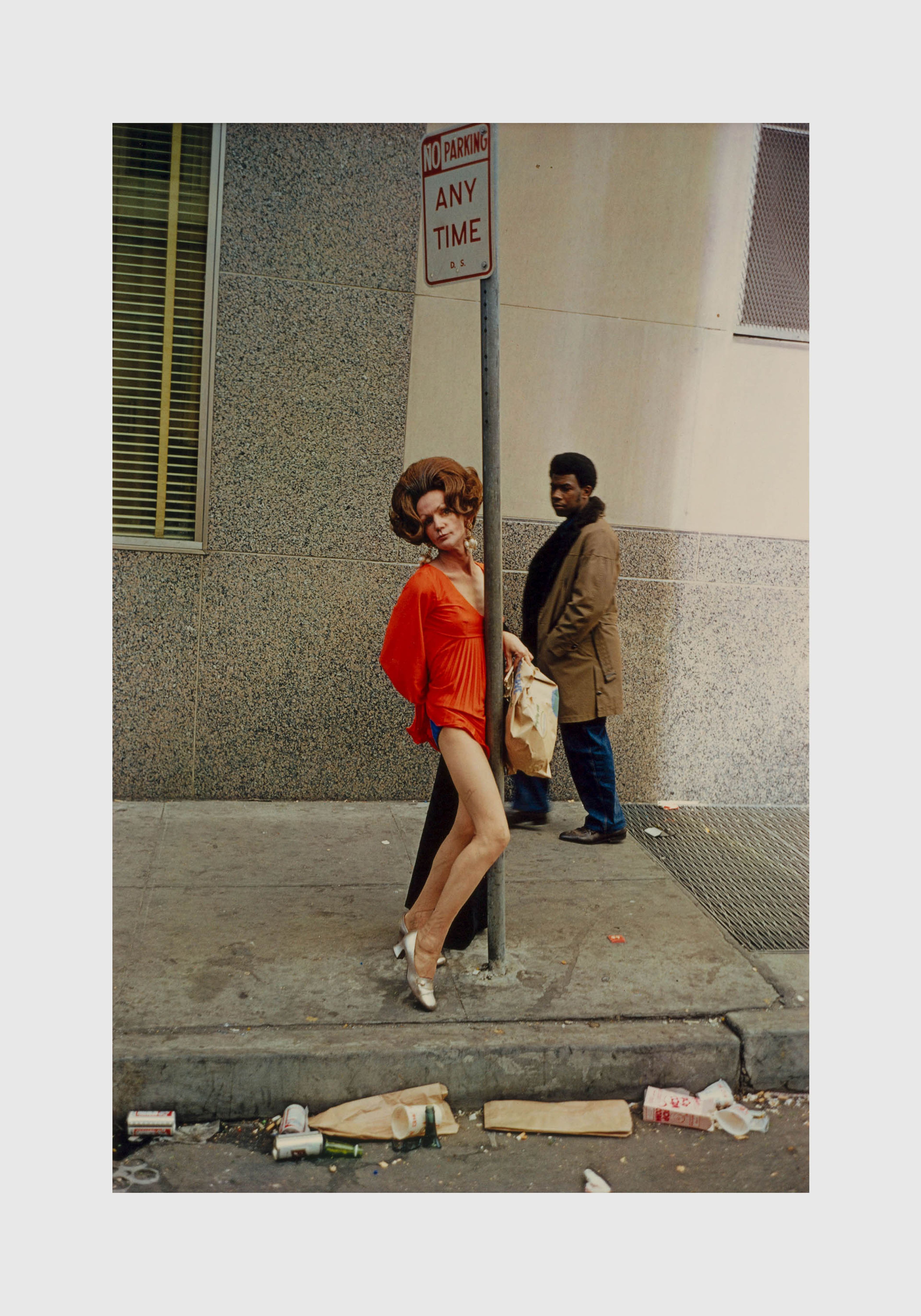

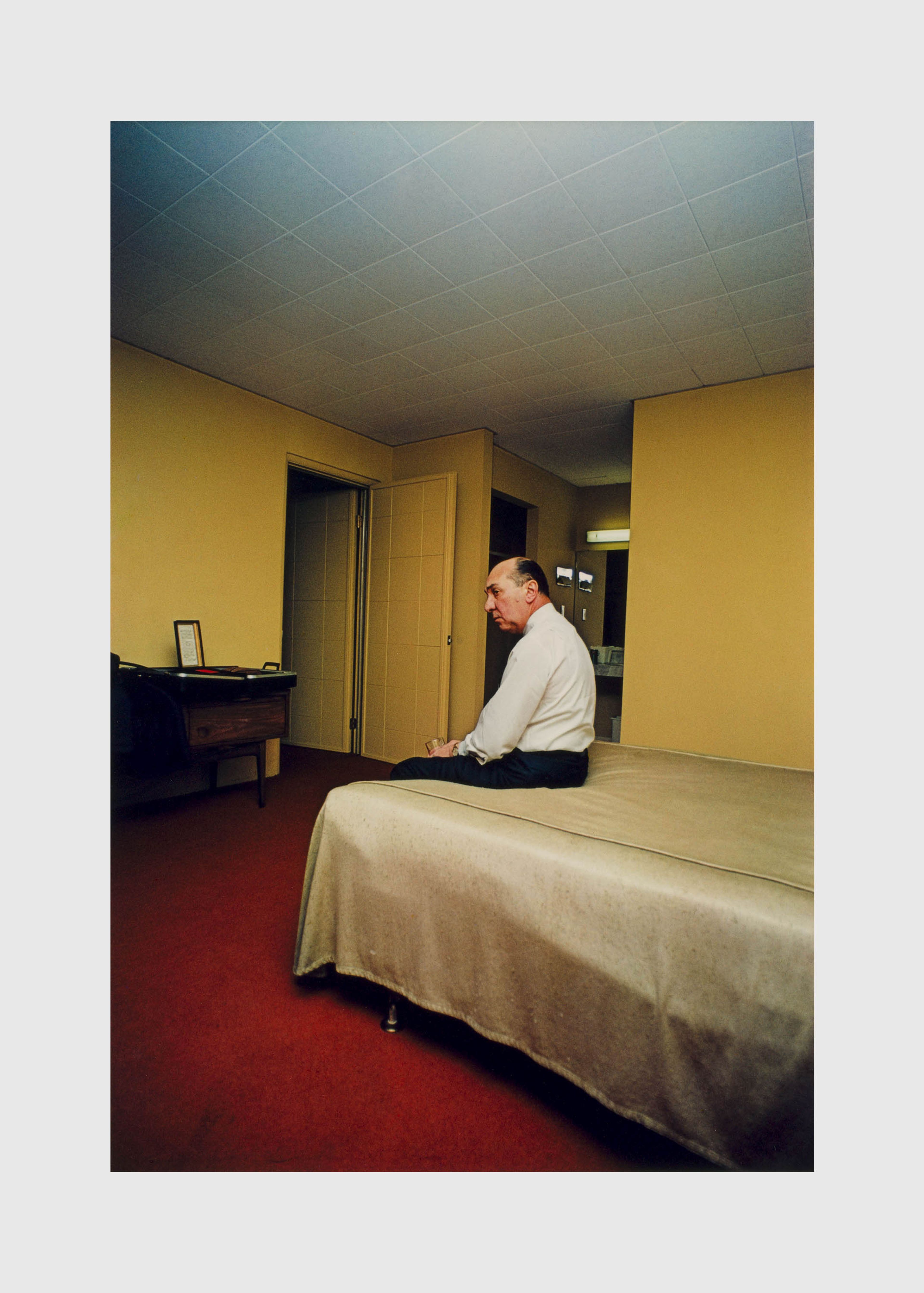

Eggleston’s discovery of the dye-transfer process in the 1970s—primarily used in advertising at the time—was crucial to his move from primarily working in black-and-white to producing color photographs. As the exhibition title suggests, the works on view in Los Angeles are the final prints ever to be made of Eggleston’s images using this inimitable analog process.

“[The dye-transfer] technique allows William Eggleston to subjectively control colors like a painter. And this manner of interpretation contributes to the fact that you often have the feeling of consciously seeing an object for the first time.”

—Thomas Weski, curator

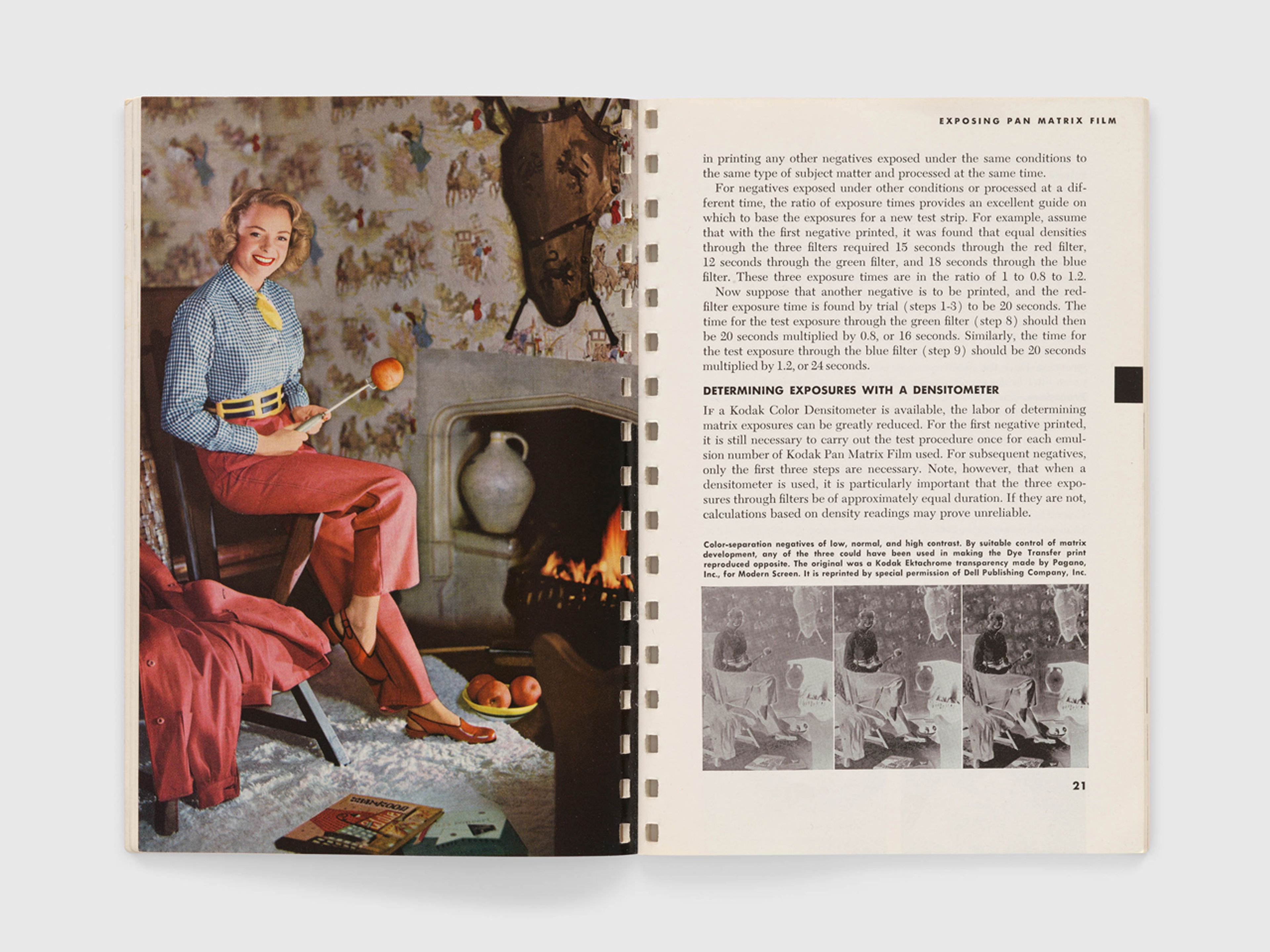

Interior spread, Studio Light: Presenting the Kodak Dye Transfer Process, published in August 1946

Cover of Color Separation and Masking: A Kodak Color Data Book, published in 1956

Interior spread, Kodak Dye Transfer Process: A Kodak Color Data Book, published in 1951

The dye-transfer process and materials were developed by Kodak in the 1940s, primarily for fashion photography and commercial use. More akin to offset printing, the dye-transfer process is a technically advanced undertaking done by hand in which the original image is split into three separation negatives. These are then enlarged onto three film matrices—transparent cells coated with a light-sensitive emulsion—as positive images.

Footage of the dye transfer process

“I remember being amazed at what [Eggleston] had done, looking at some of [his] first color stuff. It was the first color photography I’d ever seen that was equal in technical quality to advertising photographs.... It was a great historical moment.”

—Stanley Booth, writer and journalist

“Dye transfer prints were expensive and rare.... When they did their job well they were, like Marilyn Monroe, better than anything else around.”

—Richard Benson, photographer, printer, and professor

Installation view, William Eggleston: The Last Dyes, David Zwirner, Los Angeles, 2024

Footage of the dye transfer process

Each of the three film matrices is immersed in a dye bath of cyan, magenta, and yellow, respectively, with the gelatin on the matrices holding the dye. One at a time, the individual matrices are pressed and rolled onto a special fiber paper that is highly receptive to the dyes, resulting in the final color photograph.

“On one level, a photograph is simply a mixture of cyan, magenta, and yellow dyes printed on paper. But the human traces Eggleston has chosen to depict in his photographs are as inescapable as the fact that that search is what makes us human.”

—Donna De Salvo, curator, Dia Art Foundation

Footage of the dye transfer process

The process requires multiple steps and the exacting alignment of each layer of dye, making it a time-consuming, labor-intensive technique that was seldom used by amateur photographers. The resulting prints are therefore quite rare, and their appearance has a physicality and built-up surface that almost resembles that of a painting. For Eggleston, the process allowed him to achieve the richness of tonal depth and color saturation that he had been searching for.

“The process of making prints, at the time crucial for color, was something that always interested Eggleston. It was not until he discovered the dye transfer process in the late sixties that he gained control over color shading, and was able to impose a palette that came to be seen as the ‘Eggleston touch.’”

—Agnès Sire, former director, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

William Eggleston and Guy Stricherz, 1999. Photo by Winston Eggleston

In the early 1990s, Kodak stopped producing the dyes, paper, and the Matrix film used in the process. At that time, Eggleston and the renowned dye-transfer specialists Guy Stricherz and Irene Malli—who have printed Eggleston’s works for the last twenty-five years—began acquiring the remaining available dye-transfer materials, using the last significant quantities of them to produce these final photographs.

With the necessary materials now discontinued, and the bulk of what remained being used for this exhibition, The Last Dyes marks the final presentation of new works completed in this medium.

“Amidst the splintered vision of [Eggleston’s] work, there exist meticulous patterns and a discipline with which he can study flower petals or hand-guns, mansions or trash.... He continues to cut to the heart of the ordinary, probing at those things which constitute tangible dimensions, like some concrete explorer.”

—Mark Holborn, editor and writer

Installation view, William Eggleston: The Last Dyes, David Zwirner, Los Angeles, 2024

Inquire about works by William Eggleston