Exhibition

Giorgio Morandi: Masterpieces from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation

Want to know more?

Past

January 16—February 22, 2025

Opening Reception

Thursday, January 16, 6–8 PM

Location

New York: 20th Street

537 West 20th Street

New York, New York 10011

Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri, Sat: 10 AM-6 PM

Artist

Curators

Dr. Alice Ensabella

Installation view, Giorgio Morandi: Masterpieces from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, David Zwirner, New York, 2025

Explore

Inquire about works by Giorgio Morandi

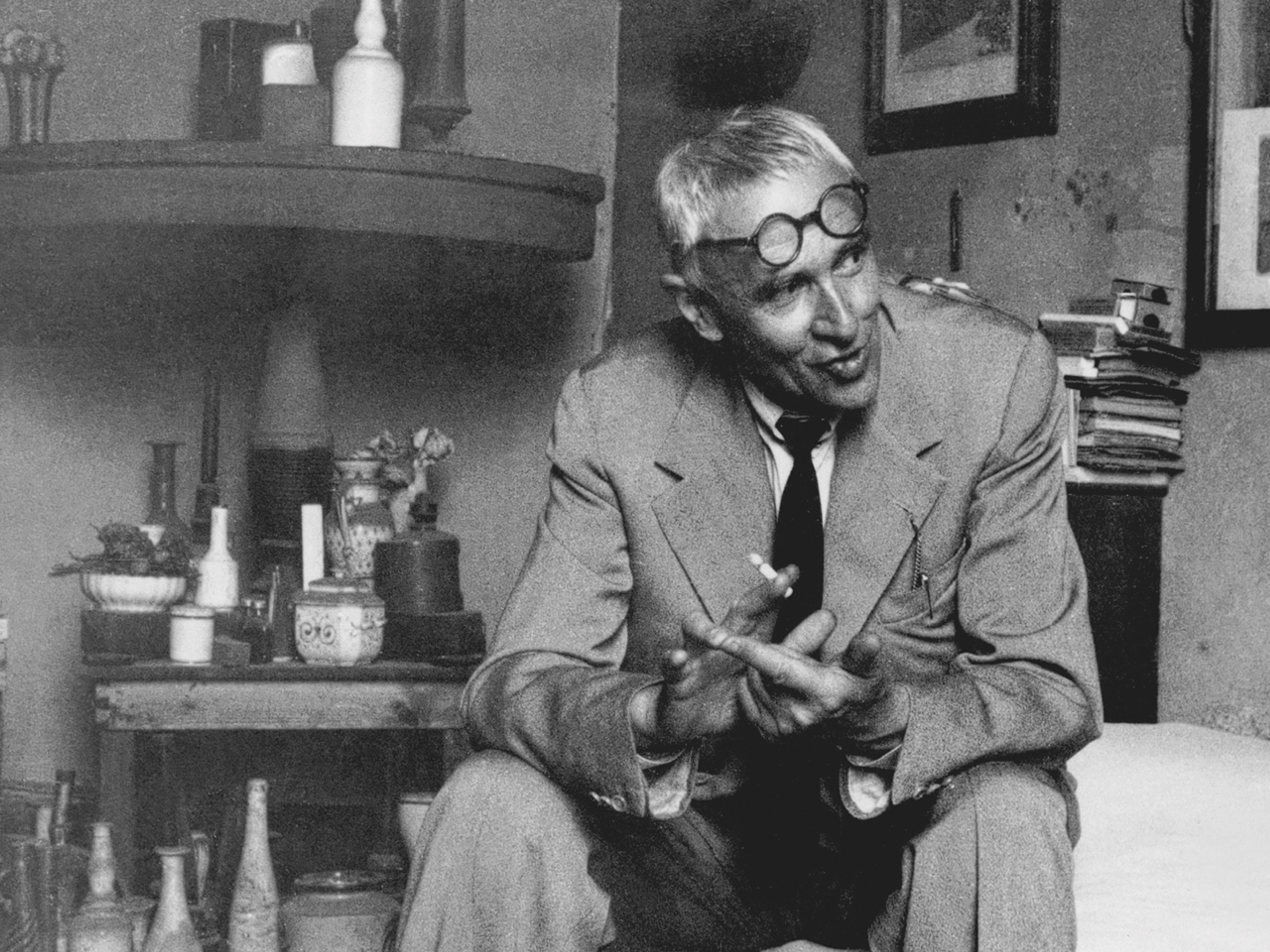

Rare footage of Giorgio Morandi and Luigi Magnani, June 1960.

“The musicologist, collector, art critic, professor, and entrepreneur Luigi Magnani became one of the artist’s most important benefactors and closest friends.... Magnani’s collection is considered one of the most significant ensembles of Giorgio Morandi’s work, notable for its exceptional quality and the variety of techniques, subjects, and periods it represents.”

—Alice Ensabella, curator of Giorgio Morandi: Masterpieces from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation

Luigi Magnani in front of his villa, Mamiano di Traversetolo (Parma), Italy, c. 1960s. Courtesy the Magnani-Rocca Foundation

“There is a certain childlike primitive charm in his 1912 Cézannesque landscape etching.... In this print ... are strange dots or marks that were not made with the etching needle.... [Morandi] explained that it was a technique, similar to one that Rembrandt has also used once. By sprinkling powdered sulfur on the plate and allowing it to ‘sit’ there, the sulfur acts as a mordant giving ... a wash-like tone. This was the only time that Morandi would use this particular process.”

—Janet Abramowicz, artist and writer

Luigi Magnani showing Princess Margaret his Filippo Lippi work Madonna and Child, 1984. Courtesy the Magnani-Rocca Foundation

“It is as if [Magnani] were still saying to us today: read, look, listen with your senses and your heart. Let yourself be pervaded by Beethoven and Proust, by Stendhal and Goethe, lighten your existential burden with Cézanne and Morandi, with Dürer and Goya, with history and nature, which time makes even more seductive, fluid, and penetrating, until it surpasses every deeper opacity, like a recognizable and familiar perfume.”

—Lucia Fornari Schianchi, art historian and author

Luigi Ghirri, Atelier de Giorgio Morandi, Bolognia, 1989–1990. Courtesy the Archives Luigi Ghirri © Eredi di Luigi Ghirri

The 1936 still life above exemplifies Morandi’s meditative approach to ordinary objects, and is one of the first in a long series of works that features variations on a set of recurring items: two blue bowls, two white vessels, a white vase, a sugar bowl, and a spherical toy, represented in many different combinations. Each object is rendered with a serene stillness, frozen in time and bathed in warm, diffused light that creates an atmosphere of quiet intimacy. The influence of Chardin and Vermeer—two of Morandi’s self-proclaimed idols at the time—is evident in the harmonious palette of yellows and blues, as well as in the reverence for humble, domestic subjects. With meticulous precision, Morandi arranged, rearranged, and altered these objects, studying their forms, light, and shadows, foreshadowing the ethereal stillness of his later works.

Giorgio Morandi and Luigi Magnani, 1964. Photo by Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved

Magnani supplied the specific items he wished Morandi to depict: “an old Venetian lute, two Indian flutes, and other precious instruments lent by a friend.” But Morandi, feeling compelled to fulfill the commission despite his discomfort with the opulent and fragile nature of the items, ultimately replaced them with the toy trumpet, flea-market guitar, and old mandolin depicted in the final work.

Alice Ensabella, the exhibition’s curator, explains: “Beyond its anecdotal and amusing nature, this exchange reveals much about the rigor and depth of Morandi’s artistic approach, which Magnani later recognized—regretfully—as something he had not understood or respected at the time. ‘Only later did I understand the discomfort he must have felt at deviating from his usual conception of a painting,’ Magnani wrote, ‘undertaking a dialogue with elements completely foreign to his history, and subjecting them, without any desire, to the slow process that transforms them, like a caterpillar into a butterfly.’”

Installation view, Giorgio Morandi: Masterpieces from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, David Zwirner, New York, 2025

“[Morandi erased] all signs of the lived life from his props. He removed labels from his bottles.... His clocks have no faces, his landscapes are without people. The seeming neutrality and constancy of Morandi’s work leaves no room for projection and has allowed artists and others to take from it many things.”

—Donna De Salvo, curator, Dia Art Foundation

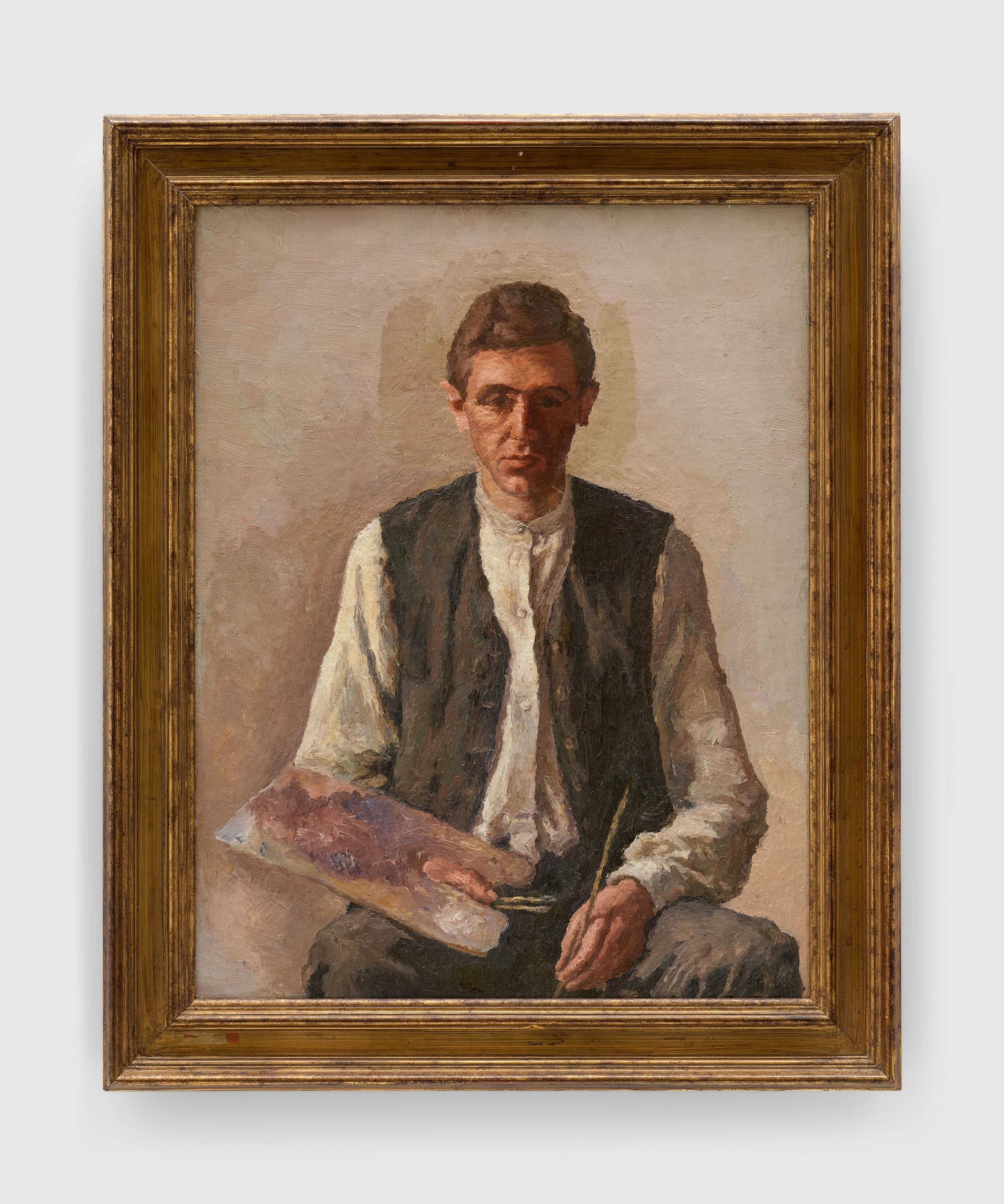

Giorgio Morandi in his studio, 1955. © Photo by Leo Lionni. Used with permission of the Lionni family

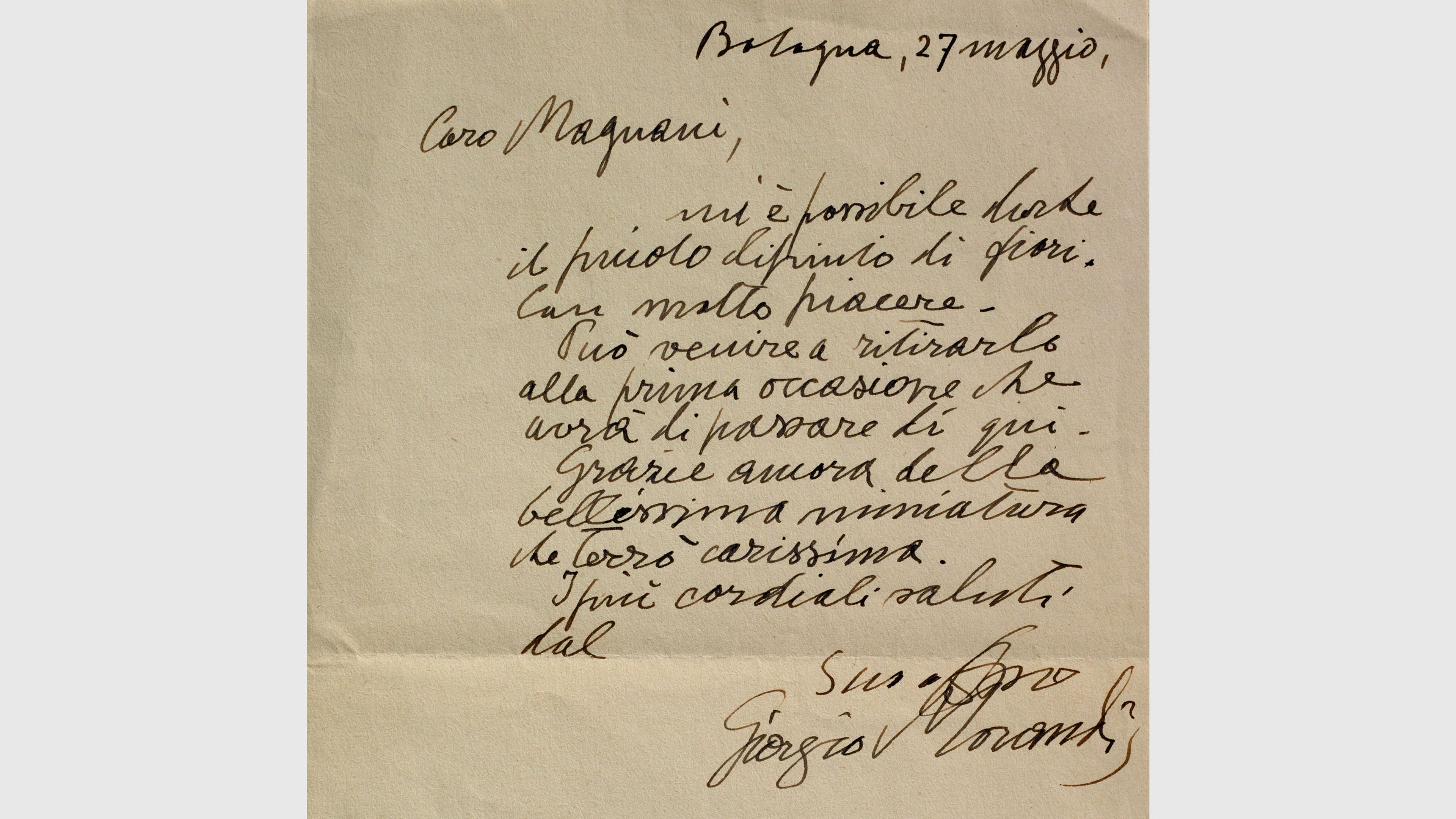

Letter from Giorgio Morandi to Luigi Magnani, April 10, 1954, which reads: “Dear Magnani, I am sorry that you are not yet back to full health. I am sending you my best wishes for a swift and complete recovery. I am pleased that you liked the painting with the three white bottles. You don’t owe me anything, I would really like to give it to you. Thank you for your Easter greetings; I send my own to you and your loved ones. Warmest wishes and fond regards, Giorgio Morandi”

Morandi’s still lifes from the years following the war remain celebrated for their subtle variations in light, tone, and composition. These works are considered masterpieces of quiet introspection and refined technique, in which the objects depicted are less and less defined by drawing and chiaroscuro and increasingly by color. By clustering his vessels toward the center of the canvas and in symmetrical, compact arrangements, Morandi accentuates the architectonic and abstract nature of their forms. The emphasis on tonal variation and spatial ambiguity exemplifies Morandi's longstanding concern with space, light, color, and form over subject matter—aspects that had a profound influence on twentieth-century and contemporary art and painting.

Installation view, Giorgio Morandi: Masterpieces from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, David Zwirner, New York, 2025

“The whole history of modern art passes through the still life—from Cézanne to Picasso, from cubism to Dadaism, from metaphysics to surrealism and pop art. To have painted in this genre right from the beginning and to have explored it with unswerving dedication certainly meant for Morandi never abandoning an investigation that placed him at the heart of the problems of modern and contemporary art.”

—Laura Mattioli, art historian and curator

“Morandi's etchings certainly occupy a special place in Magnani’s collection, representing more than half of the works he owned by the artist. As we have seen, Morandi gave Magnani three etchings after their first meeting, thereby revealing to his new friend the importance that this technique had for him.”

—Alice Ensabella, curator of Giorgio Morandi: Masterpieces from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation

Luigi Ghirri, Atelier de Giorgio Morandi, Bolognia, 1989–1990. Courtesy the Archives Luigi Ghirri © Eredi di Luigi Ghirri

Installation view, Giorgio Morandi: Masterpieces from the Magnani-Rocca Foundation, David Zwirner, New York, 2025

“Not unlike Cézanne who affirmed the necessity of artists having to consider themselves artisans of their own art, of having to be painters with the accomplishments of painters, utilizing materials as naturally as possible, Morandi, too, worked with the care and at the slow pace of an ancient artisan, constantly striving to plumb the depths of his own profession ever further, one eye turned to the masters and the other to nature.”

—Luigi Magnani

Footage of Luigi Magnani and his family and friends in his villa and gardens, Mamiano di Traversetolo (Parma), Italy, c. 1960s. Courtesy the Magnani-Rocca Foundation

Inquire about works by Giorgio Morandi

![A print by Giorgio Morandi, titled Natura morta con il cestino del pane (Lastra grande) (Still Life with Bread Basket [Large Plate]), dated 1921.](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/juzvn5an/release-adp/fe1904f84394b4f20d5390ca04f4cee6ffde40d2-2829x3000.jpg?w=3840)

![An artwork by Giorgio Morandi, titled Natura morta con il cestino del pane (Lastra grande) (Still Life with Bread Basket [Large Plate]), dated 1921](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/juzvn5an/release-adp/fe435431e02a29addf9c74e557ad6b0d058167ee-2800x1576.jpg?w=3840)

![A painting by Giorgio Morandi, titled Natura morta (Strumenti musicali) (Still Life [Musical Instruments]), dated 1941.](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/juzvn5an/release-adp/12b81c508dbd74442bbcd381cab3b3ca6b4ec7f1-3000x2144.jpg?w=3840)