'The Pleasures of Slow Paintings' by John Yau

September 2017

These paintings are what the artist Suzan Frecon calls “slow,” meaning that they reveal themselves quietly over time.

I began looking at Suzan Frecon’s work shortly after I got to New York in 1975, when she had no gallery, and have been following it ever since. In 2005, when she was able to show her large paintings for the first time in New York, having previously shown small paintings and works on paper, I interviewed her for The Brooklyn Rail (November 2005). One of the things that she said in that interview has stayed with me:

"All my decisions are made for visual reasons."

Inspiration, no matter what it might be, can never be the justification for a painting’s existence. In this, Frecon shares something with another abstract painter, Thomas Nozkowski. The difference is that Frecon works on a much larger scale, with a much smaller vocabulary. In that same interview, Frecon expressed her admiration for art that was ‘anonymous” and reached “a high plane of abstraction.” This goes against the commonplace model in which artists explain what they are to up, and how it is relevant, producing a readymade text of meaningfulness (or creative unmeaningfulness) that can be replicated in various ways.

As curious as we might be about what prompted a painting by Frecon — and it is never really just one thing — an attempt to discover it seems almost beside the point. Here, the critic must avoid the pitfall of showing off how many clever associations (or visual similarities) you can come up with. I think this is why people dislike certain kinds of painting so much: they cannot say what it is. They don’t like that uncertainty because it reminds them that life too is precarious, with the only guarantees being, as the saying goes, death and taxes.

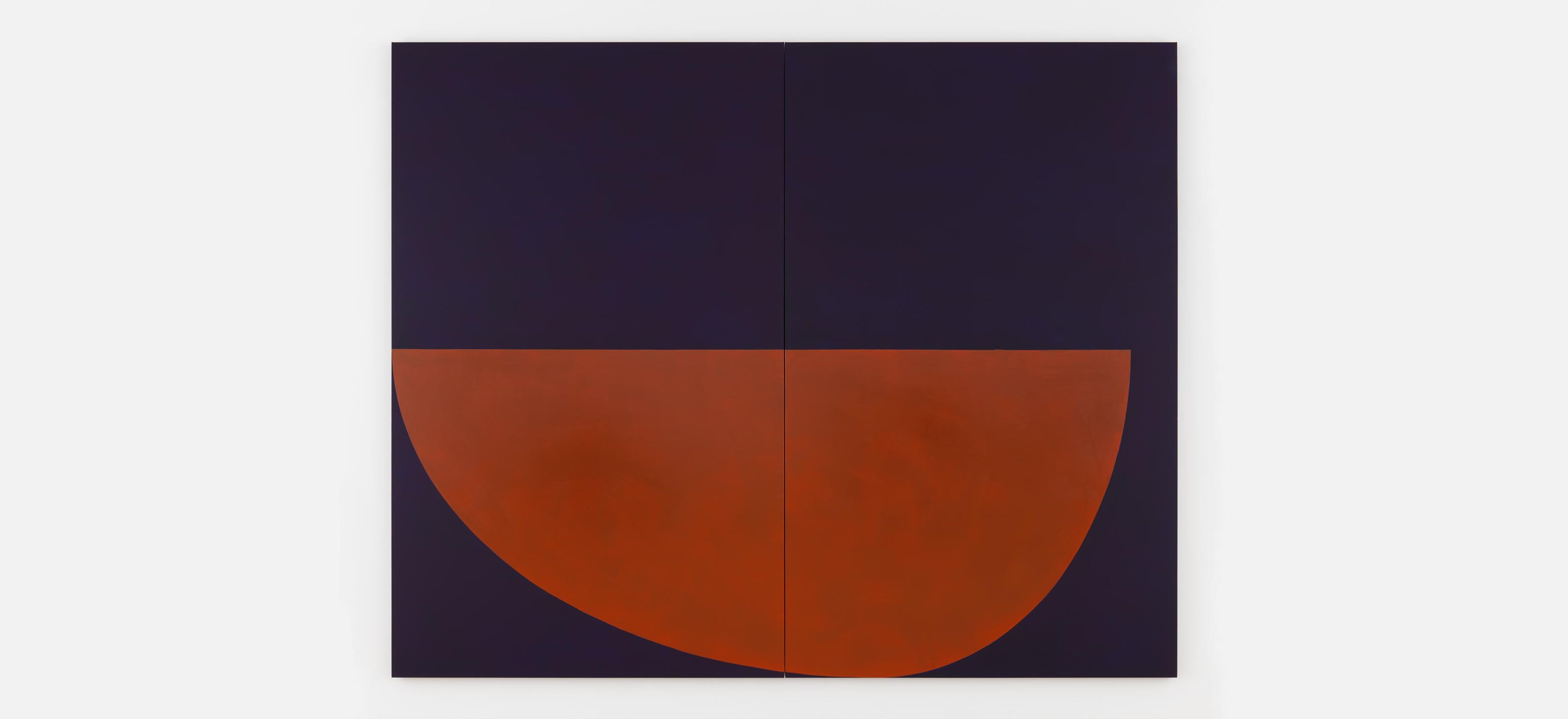

In the exhibition "Suzan Frecon: recent oil paintings" at David Zwirner (September 14–October 21, 2017), the artist exhibits seven large, two-panel paintings. In six, Frecon works with two colors, one for the figure (an elliptical or a semicircular abstract form) and one for the ground. The figure has a glossy, lacquer-like surface, while the ground is more thinly painted and matte. The material differences affect the painting in a number of ways, including its relationship to the ambient natural light filtering through the gallery’s skylights, and not supplemented by artificial lights. The day I visited the show was cloudy, and so the light in the gallery felt gray and muted.

There is a bench to sit on in one room, where there is one painting, “noh” (2017), hanging, but none in either the front gallery or the large main gallery, and there should be. These paintings are to be contemplated from afar as well as walked up to and scrutinized. They are what the artist calls “slow,” meaning that they reveal themselves quietly over time. They are an anomaly and have more in common with Ad Reinhardt, whose “Blue Paintings” are on display in Zwirner’s other Chelsea gallery space, than they do with the work of Frecon’s contemporaries. Partly this has to do with her temperament, but it is also her response to the revelatory Hilma af Klint show that Frecon saw at PS1 in 1989, which helped her return to geometric forms, which she abandoned earlier in her career to concentrate on colors and paint strokes.

In “noh” (2017), a cadmium red half-moon extends across most of the painting’s two terre verte panels, its rounded edge touching the left panel’s top left corner while drifting just below the right panel’s top edge. I wrote “half-moon,” but I immediately want to qualify that description. The right side of the form is a skewed quarter-circle, stretched between the panel’s right and left edges. The other part of the shape extends across the width of the left panel not all the way. Its curve is more rounded. Do each of the shapes occupy the same amount of area? What about the severity of the red shape’s bottom edge, which cuts across the surface of both panels like a scalpel? It is as if the muted, matte green ground falls below the form it appears to be physically holding it up. How can that be?