Bridget Riley Reviewed by Jonathan Jones

January 2018

To walk into Bridget Riley’s exhibition of new works – everything here, with a couple of exceptions, has been created in the last four years – is to see a mighty brain fizzing away with ideas that blow away all the sentimental cobwebs from art. Riley is a philosopher who is interested in perception – and nothing else. For her, a work of art is not a picture nor a political comment nor a splurge of self-expression. It is a way to explore seeing. If it does not leave you with your sense of the visible world shaken and reborn, what’s the point of it?

In the early 1960s, she took on the epic sweep of American art and gave it a sharp scientific twist. Jackson Pollock’s paintings absorb the beholder in poetic tangles and forests of colour. Riley liked the scope and sweep, yet she put it all in a more solid psychological basis. The curves and eddies, twists and vortices of her early black and white paintings such as Hesitate (1964) are mathematically calculated. Their discombobulating effects are precisely planned. They turn perception inside out as you find spaces move and melt, shapes materialise in front of the canvas, reality itself burst open to reveal new dimensions. In the decade of psychedelia, Riley invented a legal hallucinogenic.

Her new exhibition harnesses that drug again. I confess that I was expecting to respect this exhibition rather than enjoy it. Riley has continued to explore abstract art all her life, in inventive and thoughtful ways, but often with quieter, calmer results than her early, revolutionary art.

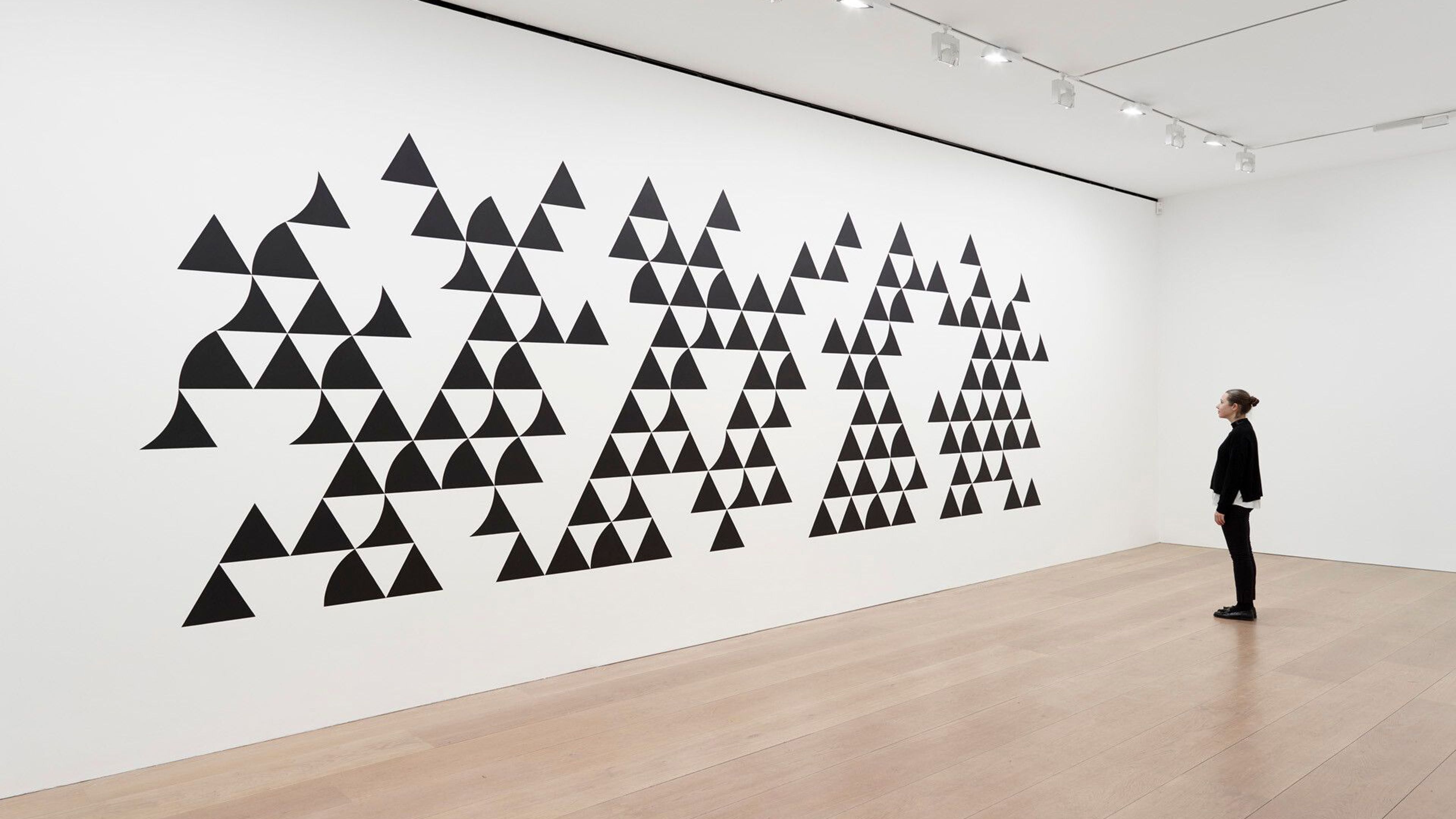

What a thrill that in her new show she unleashes once again the monochrome psychedelic energy of her youth. A gigantic wall painting interlaces black and white curves and triangles with what seems at first like a calm geometrical elegance. Shapes tessellate like the patterns of medieval Islamic tiles in the Alhambra. But then, as your eyes adjust ... they can’t quite adjust. There is somehow too much to take in. The rhythm this jazzy mural creates is so complex and strange it befuddles your brain.

Perhaps the framed paintings would be easier on the eye. But no. Looking at Cascando and Rustle 6 – both painted in 2015 – I find myself seeing depths where there are no depths, a sublime architecture of black boxes appearing and vanishing. It is dizzying and disorientating.

The rest of the exhibition is more like what I expected of later Riley - but scintillating all the same. In a sequence of paintings called Measure for Measure, she plays with patterns of circles in just three colours – purple, orange and green. All three colours are warm, slightly muted, richly suggestive. I was so struck that I asked for an exact definition of them. The answer that came back from Riley’s studio: "They are purple, orange and green."

The way these dots interact is a 21st-century echo of the pointillist paintings of Georges Seurat, whose art Riley studied and copied when she was developing her concept of perceptual art. On the other hand, perhaps she did the Measure for Measure series to show Damien Hirst who’s boss.

We don’t have many artists in British history who rethink the very nature of perception as it was rethought by Cézanne, Picasso or Seurat. You could set the paintings in this exhibition beside a cubist masterpiece from 1910, a Cézanne view of Mont Sainte-Victoire or Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings and the dialogue would be fascinating. Or if that sounds too hifalutin, let’s just say Riley’s recent work blew my mind.