Bridget Riley Review by Emily Gosling

January 2018

Like psychedelics for the puritanical, Bridget Riley’s work – not at its best as digital image files – has utterly mind-altering power. Looking long enough at it makes the eyes and the mind perform bold gymnastic leaps, as we weave our perceptions into hers and see things that aren’t there as fact, but very much are there as viewers.

That dichotomy between what is there, and what we see, is at the heart of the famed op artist's practise. “You have to be willing to look, and able to look,” Riley tells us at the press view of her new show, Recent Paintings, 2014 - 2017. “But there’s no must about anything.” She adds, “what I see, other people will see, and that's a dialogue you have.”

All the works in the show, which span the entire three floors of the David Zwirner gallery in London’s Grafton Street, were created in the past three years, making them the most recent (as the show title suggests) of the now-86-year-old’s career.

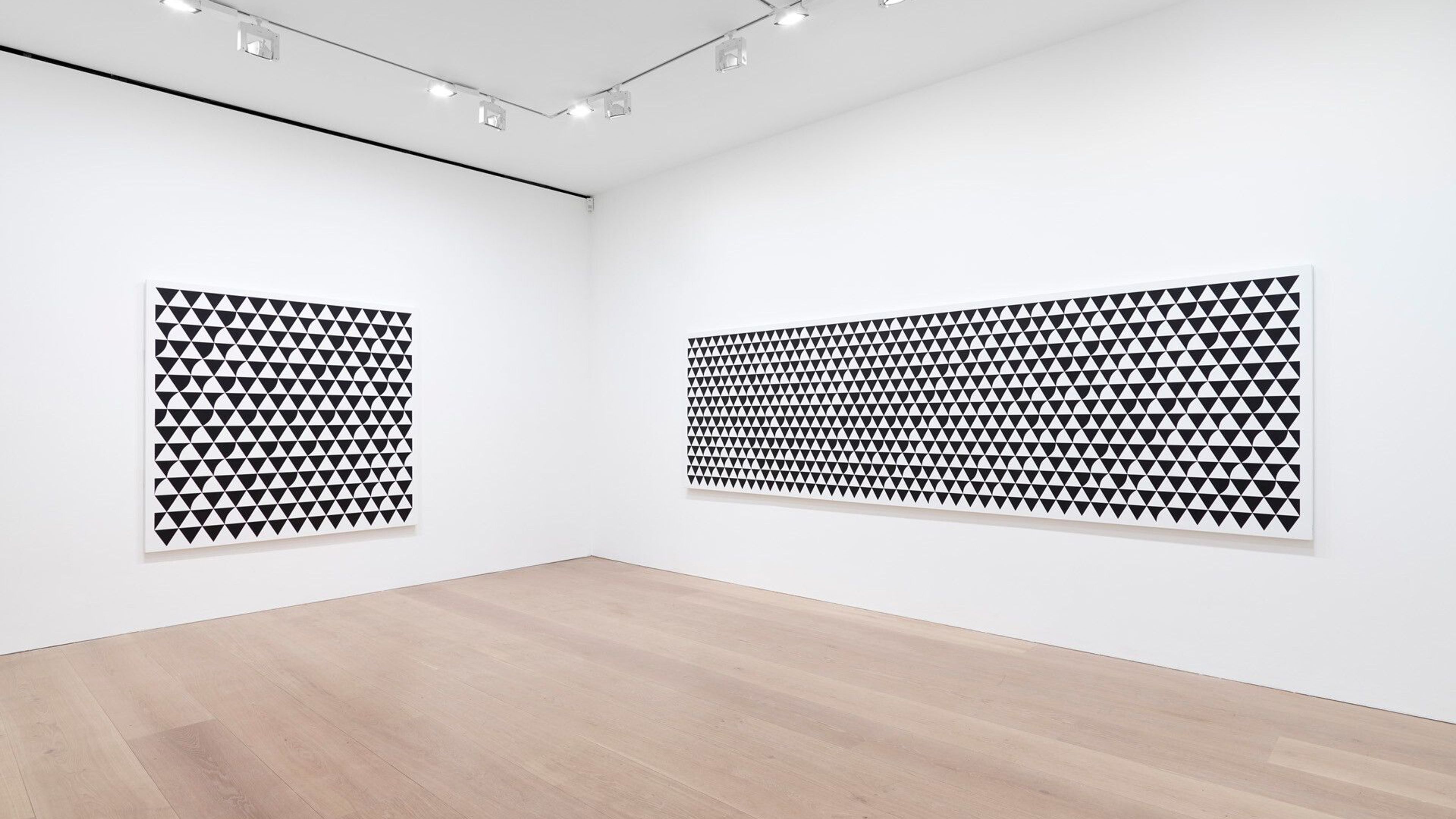

In the opening ground floor space, Riley’s work takes the form of vast monochrome patterns which form a sort of undulating geometry. We have to be careful with that last word, though – according to director of the Contemporary Art Society Caroline Douglas, who takes us around the show, Riley “doesn’t view them as geometric forms.” Instead – in the case of these monochrome works – the triangles “have a neutrality”, and refer to the patterns we find everywhere in nature, and in life generally. The triangles, then, are like the ‘X’ in a mathematical equation: they can represent anything and everything.

Black and white, in Riley’s hands, can be as vibrant and arresting as the most neon of hues or busy of rainbows. The artist looks back through art history to the likes of Velazquez to make this point, indicating that black and white have the capacity to make you all the more aware of how your visual perception actually functions.

Alone, on the wall, the points where black meets white become charged with an extra sense of intensity and dynamism. Their place in the first room of the show, as Douglas puts it, is an “opening declaring of intent,” in which the “wall is no longer a wall, the wall is a canvas.”

We’ve said it before, and we’ll say it again; these works require (and fully deserve) extended contemplation, and really looking. Just as Riley’s art career has been imbued with a glorious spirit of constant enquiry, so the viewers are invited to enquire and interrogate the forms she paints solely by looking.

It’s a somewhat meditative practice, all that looking. The mind creates fantastical forms and hallucinations: Riley goes as far as to say the works in fact only exist with the active participation of her viewers. This is best explained by one of the works on the top floor of the show, a series of disk-shaped marks in three shades of what Riley terms ‘grey’ (to us, they look like bluish grey, green and orange.)

On gazing at it, even for a short time, something “more develops,” to quote Riley herself. As you look away, then back again, new disks form from retina-trickery and the mysterious workings of the human mind. “You will see little bursts of light in the after-image,” says Riley. “You are creating the painting by looking at it.”