Michael Glover on Thrust: A Spasmodic Pictorial History of the Codpiece in Art

October 28, 2019

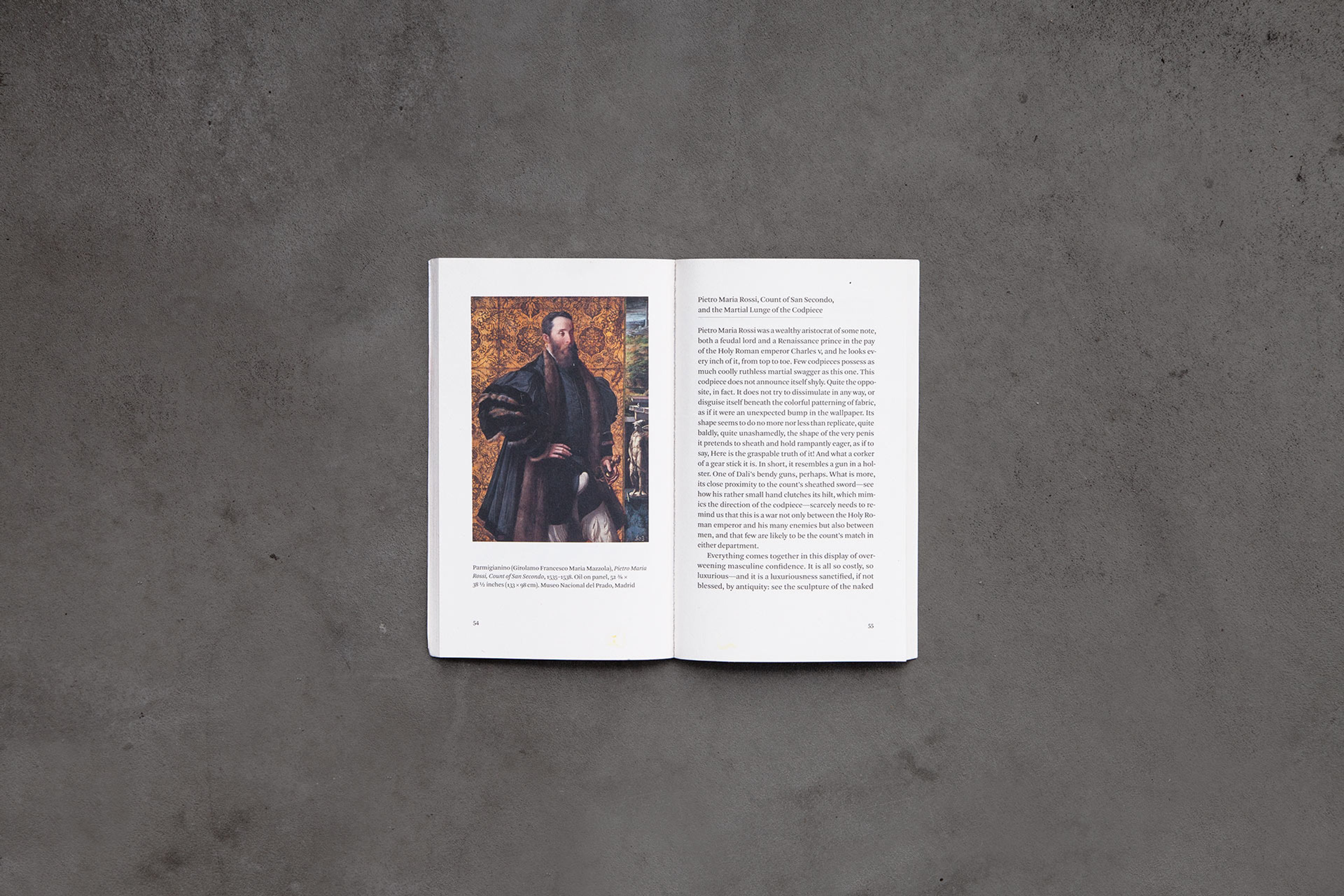

In Thrust: A Spasmodic Pictorial History of the Codpiece in Art, the London-based poet and art critic Michael Glover takes on the strangest piece of men’s clothing ever created. This laugh-out-loud visual history pulls in writers from Rabelais to Shakespeare, as well as figures from Henry VIII to Alice Cooper. Glover’s witty and entertaining prose reveals how male vanity turned a piece of cloth into a bulging and absurd representation of masculinity itself.

In what context did you come up with this idea, and what clinched the decision to do it? Was there a particular painting that kicked things off?

It happened one chilly Saturday morning in winter a couple of years ago. Call it a love affair of sorts, if you like. Saturdays I feel off-duty, footloose as an art critic. I tend to wander around some of my favorite museums and galleries. The National Portrait Gallery is one of these. It is full to the gills with paintings of British worthies stretching back five hundred years.

That morning, I went directly up to the gallery which houses the oldest paintings in the collection, where the portraits of the Tudors live. It is a mysteriously low-lit space. I found myself standing in front of a cartoon by Holbein the Younger of Henry VIII and his father, Henry VII. I stared and stared at Henry VIII, mesmerized by his massive, spread-legged presence in front of me. I could not stop myself concentrating on the object which seemed to be at the dead center of the painting: Henry’s giant codpiece, curled there like a monstrous snail. The entire world seemed to pivot about it. As I looked, I thought to myself, there are many portraits of famous men of the sixteenth century wearing codpieces. Surely there has been a book about them? As I thought about that book, its inevitable title seemed to arrive as if from nowhere: Thrust. There was no such book in existence, I quickly discovered. It seemed incumbent upon me to write it.

Can you elucidate the Paul Hodgson quote at the beginning?

What better way to answer this question than by asking Paul Hodgson himself to do so?

[Paul Hodgson]: Michael [Glover], his wife, the artist Ruth Dupré, and I were making our way to a Georgian café in Clapham South, in London, discussing the poems of Federico García Lorca. Did we order the Khachapuri bread with Georgian beans? Soon after we sat down, Michael mentioned in passing a certain work in progress, a “spasmodic history of the codpiece.”

I immediately thought of Bronzino’s Portrait of a Young Man, because of the angle of his pose, groin pushed close to carved furniture, finger tight-wedged between the soft leaves of a book. The subject looks away and to the side. There’s a sense of inflated assumption. As we savored our late breakfast, the sheer audacity of Michael’s project mingled in my mind with that portrait, and a line came into my head that would call for subservience in the face of his finished piece.

Which artwork is your favorite, and why?

It has to be that portrait by Titian of the Holy Roman Emperor in the company of his crotch-curious hound. The sheer comedy and absurdity of it is so winning. He seems so utterly indifferent to what we find so enthralling: the closenesss of the hound’s muzzle to the codpiece; how the bestial questing-ness of the dog’s elongated snout seems to mimic its very meaning. That phallocentric man’s man Titian was paid handsomely for this painting. He was even gifted with an absurd title: Count Palatine.

Were there any that didn’t make the cut?

Many did not make the cut. As the sixteenth century wore on, codpieces shrank in size to such an extent that to show those later paintings (I show just one of them, of the Earl of Leicester) would have been a sad demonstration of truthfulness. It is the absurdity of the inflated dream of male potency that beguiles and delights and bemuses us. Readers, male and female alike, would have become bored and disillusioned by too much reality.

Are there any anecdotes you could share from the research or writing of the book?

One of the discoveries which most delighted me had to do with the codpiece which was worn with some swing and some swagger by the actor Rowan Atkinson, best known throughout the world as Mr. Bean. He once starred in a faux-medieval epic for the BBC called Black Adder, in which he chose to wear a giant black codpiece which he fondly called the Black Russian. Some time after the series was over, that codpiece was sold at auction by Midghams of Berkshire for $1,000. Just imagine yearning to be the proud owner of a reeking,vintage, faux-medieval codpiece! How and where in the family home would you choose to display it?

I can’t help noticing how funny and beautifully written this is, regardless—or perhaps because of—the subject matter. As a poet and author as well as a critic, can you comment on the marriage of glorious language with an inglorious topic? Perhaps there’s a tradition you’re tapping into, for example, or was this simply a chance to have fun?

Yes, I guess I am tapping into a tradition. Think of Rabelais, for example, and how wonderfully he writes of earthiness. It is a marvelous thing to read an author who, in all the elegance of his language, seems to be soaring above us all, even as his nose dives into the smut.

On this note, do you think criticism could do with more humor in general?

The most incisive criticism seems to demand humor. Writing, above all things else, must bowl along, be enthrallingly readable. Humor is one of the finest and most deadly weapons in any writer’s armory. There is nothing more exposing—more undermining—than a brilliant shaft of wit. Think of the greatest humorist of them all, Jonathan Swift.

What do you take away from this project?

Writing something which pleases oneself and satisfies one’s publisher gives any author a sense of lift and buoyancy. The human machine is functioning as it should. You feel energized. You may, after all, be on the road to something even more incisive. Provided that the car does not spin off the road.

Where do you think it might lead? Are there any other glaring subjects you think need this sort of treatment?

Too little has been written of art, aesthetics, and the Marquis de Sade.

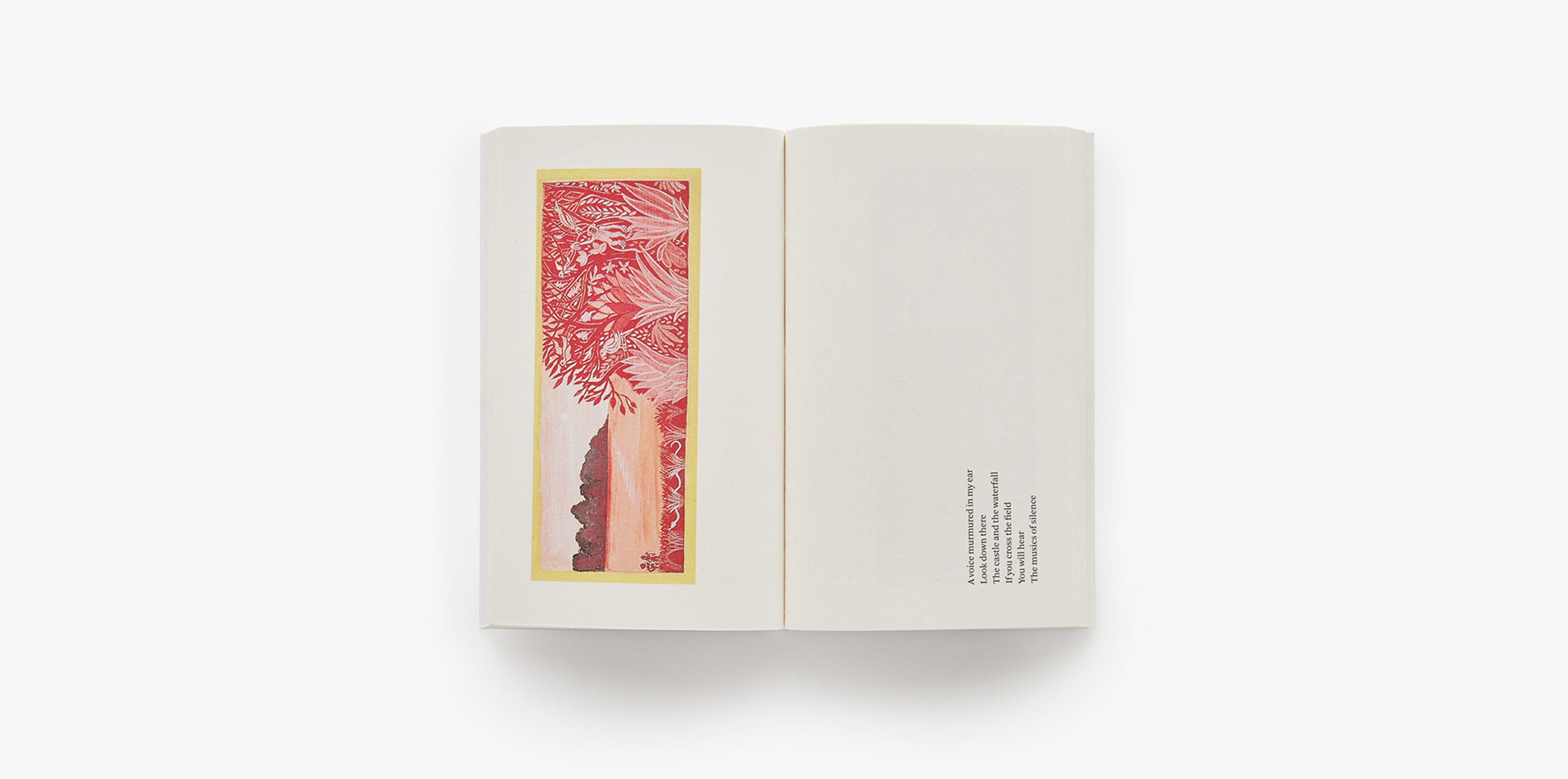

Image: Thrust: A Spasmodic Pictorial History of the Codpiece in Art, 2019