David Zwirner Books

April 30, 2020

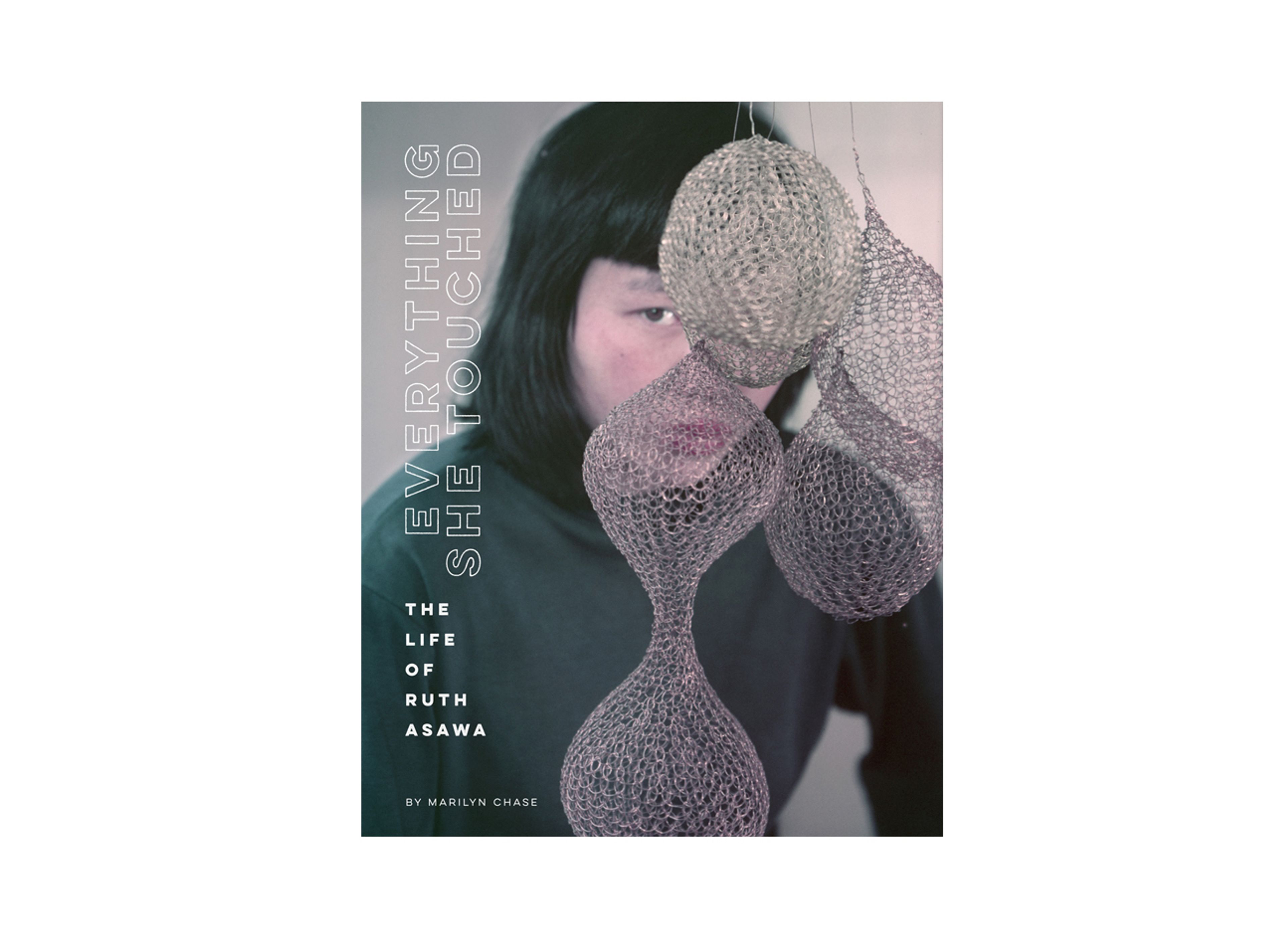

Ruth Asawa’s hands were tiny. They were also chapped—cut by the wire she worked with all her life. I know this because when she was in her sixties, she cast them in bronze, preserving her battle scars for posterity. I held the casts for a moment or so when I visited her children in San Francisco last year, and remember even now how the crinkles and ridges on the pads of her fingers bristled against my own. What can we really understand of the toil required of an artist? Or, for that matter, the sacrifices and the doubt. We only ever meet them at the point of success, when they are over the divide; a practicality that renders their years of becoming—years in which they strived and struggled and took wrong turns and probably wept—mute. Asawa, who died in 2013, created a vast body of work in her eighty-seven years. Work that remains wonderfully, irresistibly vital. She hit on her loop process in 1947 (while on a visit to Mexico, where she watched baskets being made) and became so good at it that she could work with three strands of wire at once. There were also a great many paintings, drawings, and clay models. Every surface in the house was given over to whatever Asawa happened to be working on at the time. Her children would often find pieces stuffed in the dishwasher, which had never worked. Like many other talented women of her generation, though, who came to prominence when macho abstract expressionism held sway, Asawa has only recently emerged from the “domestic artist” doldrums to which she was consigned by her critics. (Her reviews from this time, though favorable, often end with the caveat that she was “a housewife and a mother,” ergo, how could she also be a serious artist?) Other factors were in play: that she was the daughter of Japanese immigrants, for one, at a time when the Second World War still pulsed raw in people’s memories (Asawa and her family were among the 120,000 people of Japanese descent to be placed in internment camps between 1942 and 1946). And that she had committed the sin of operating from America’s West rather than East Coast, a geographical distinction about which the art world remained nonsensically sniffy until well into the 1960s. None of it diluted her drive, which all her life was urgent and compelling (it’s hard to think of another artist who cared less than Asawa about external approval, in fact). She drew near constantly, believing the practice a non-negotiable habit. Even if they didn’t become artists, she told her children, drawing would make them better at whatever else they chose to do. Asawa learned this at Black Mountain College—a short-lived, progressive arts school in rural North Carolina, founded and staffed by some of the German Bauhaus émigrés. I mention this because it was where she met the noted American architect Albert Lanier (1927–2008), who later told their children that his first sight of Asawa, coming down the path from the apple orchard there, left him smitten. The pair married in 1949. That, though, is a splinter of the story, and where I will leave you before you begin this excerpt from Marilyn Chase’s biography of Asawa, Everything She Touched. The passage covers the year that Asawsa was still at Black Mountain and Lanier was out in the world trying to get a foothold, so they could marry—no small thing at a time when public approval of interracial relationships tarried at 5 percent. The letters passed back and forth between them, and those exchanged with their families and fellow artists, reveal not only how enchanted Asawa and Lanier were by the pull of their feelings for each other, but the difficulties that their love affair presented, and how torn Asawa was all the while between having a family and making work. This is what I think about now, when I remember Asawa’s hands. What she had to overcome to be an artist; the graft involved once she had made the decision to do so, how crucial it was to her well-being, how she succeeded in folding it into her children’s lives. To follow all that as it is happening, as she is being formed, is a delight.

—Lucy Davies, Senior Arts Editor at The Telegraph

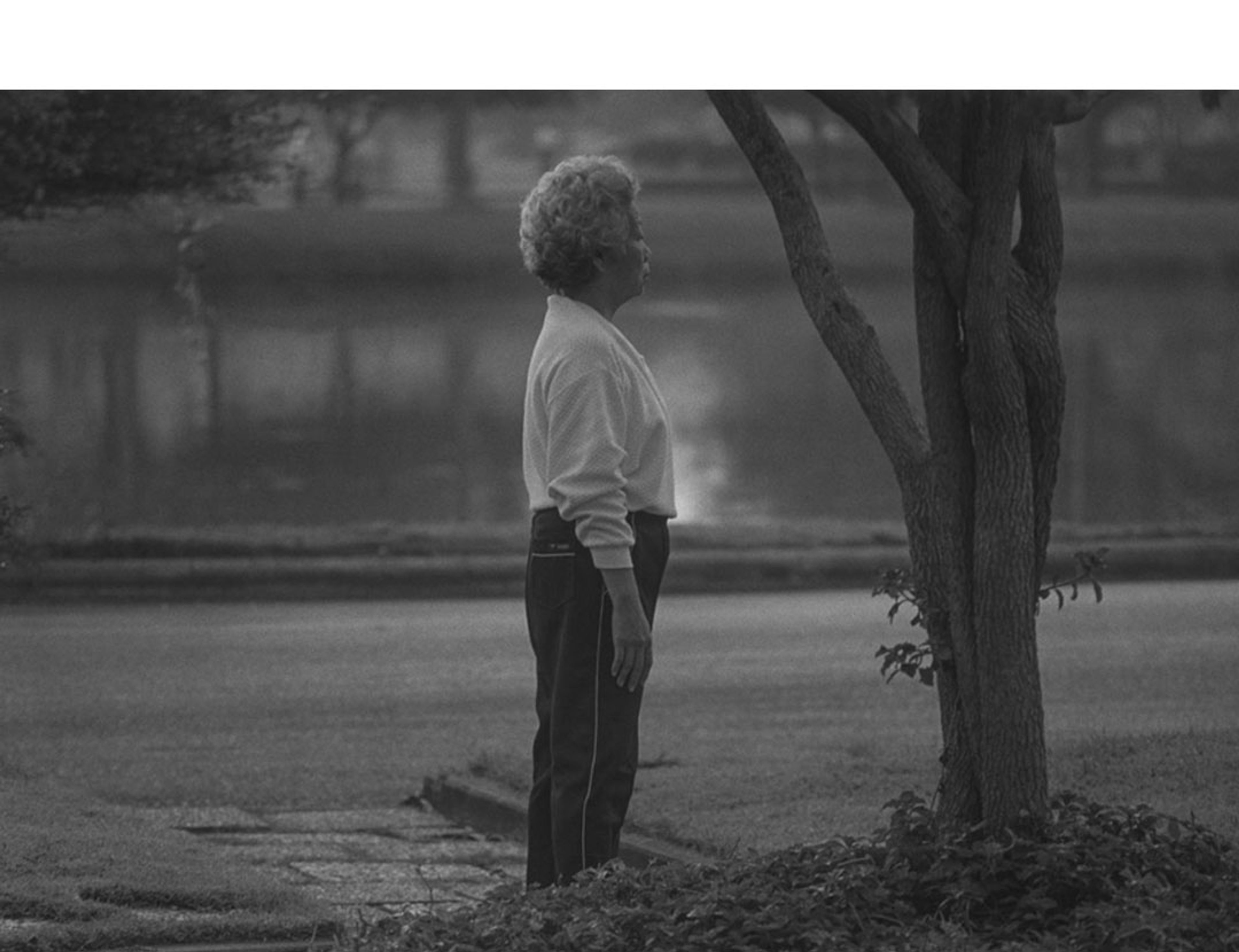

Image: Installation view, Ruth Asawa: A Line Can Go Anywhere, David Zwirner, London, 2020

Chapter 5 Love Letters Albert Lanier’s Model A jalopy was holding up and getting good gas mileage. “It’s the strangest looking car ever,” he wrote to his parents in Georgia. “Children run out and wave and flock around us wherever we stop.” To avoid the heat, Albert and his friends slept during the day and drove at night on their way from Black Mountain College in North Carolina to San Francisco. When they ran low on funds near the end of the trip, Albert resorted to selling his blood in Las Vegas. Tired from the procedure, he slept and awoke to find his traveling companions fresh from a gambling spree and sporting new shirts bought with his “blood money.” They had barely enough for the bridge toll across San Francisco Bay. He’d laugh about it later.

Read an excerpt from Everything She Touched: The Life of Ruth Asawa by Marilyn Chase, published by Chronicle Books, 2020.