Ruth Asawa: Working from Nothing

By Tiffany Bell

To see a group of Ruth Asawa’s wire sculptures hanging together is to experience an immediate sense of wonder and joy. The works have a simplicity of form, shape, and material, yet— because of the labor-intensive process of their creation and the perceptual shifts that occur as one observes them in relation to each other—the sculptures compel one to continue looking. Many of Asawa’s hanging sculptures have transparent, looped-wire surfaces and undulating, bulbous forms; they are organic and sensual. Some works are hollow and airy; in other works, the outer form encloses other forms, making certain areas dark and nearly opaque. These multilayered works can consist of a single, continuous strand of wire, looped in such a way that the interior morphs seamlessly into the exterior. This visual complexity is compounded when works are hung in groups; as one walks around them, overlapping shapes prompt a shifting sense of depth and distortion. The play of shadows adds yet another dimension.

In 1971, the renowned twentieth-century inventor and visionary Buckminster Fuller wrote a letter of recommendation in support of Asawa’s application to the Guggenheim Foundation’s annual fellowship program. After noting that he had been writing these recommendations for various candidates for forty-three years, Fuller said: “I state, without hesitation or reserve, that I consider Ruth Asawa to be the most gifted, productive, and originally inspired artist that I have ever known personally. That statement includes many of this century’s most celebrated ‘greats.’” (Fuller was close friends with Alexander Calder and Isamu Noguchi, to name two such greats.) He cited her looped-wire sculptures, with which he had been familiar since the late 1940s when he and Asawa were both at Black Mountain College In North Carolina; it was for work on these sculptures that Asawa was applying for the grant. Fuller went on to mention that Asawa was a mother of several children and had played a leading role in bringing an innovative arts curriculum into the San Francisco public schools; he also noted that together with her husband, architect Albert Lanier—she had converted an old San Francisco house into a “fascinating and inspiring” home.1

For Fuller, who considered every child a “conceptual genius” at birth and championed a multidisciplinary approach to making a better society, it is understandable that he would recommend Asawa for the breadth of her creative and social activities.2 From our perspective now, too, Asawa stands out for the remarkable range of her accomplishments. Besides creating a significant body of innovative abstract sculptures, paintings, and prints over a period of more than five decades, she and Lanier raised six children in a home they created. Also notable was the lush and productive garden they maintained in the backyard. In addition, Asawa’s work in the San Francisco schools was so successful that a local public arts high school is now named for her; she also participated on several community boards as well as the California Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts, and was a trustee of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. She produced a number of public art works, and orchestrated many participatory community events that promoted the arts as a way to stimulate awareness and creativity amongst neighbors of all ages.

But in 1971, a time in which single-minded focus and dedication to the production of one’s art was valued above all, the Guggenheim Foundation’s jury was probably not impressed by the mention of Asawa’s children and her work in public schools. The foundation gave twenty-two grants in the fine-arts category that year—only one of which went to a female artist.3 Asawa was not a recipient.

At the time, Asawa may have been best known locally for her public commissions. Her first such works were based on her wire sculptures, but in 1968, Asawa finished Andrea (PC.002), a fountain for San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square, the redeveloped, historic waterfront site of the Ghirardelli Chocolate Factory. Rather than adapting her abstract forms, as proposed by the project’s landscape architect, Asawa made a fantastical scene of two seated mermaids—one nursing an infant—surrounded by turtles, frogs, and lily pads. In 1973, she completed San Francisco Fountain (PC.004), forty-one cast-bronze panels surrounding a circular pool on a plaza outside the Hyatt Hotel at Union Square. Each panel contains historical and whimsical depictions of local landmarks and scenes, which had first been sculpted in baker’s clay, an inexpensive material similar to bread dough that Asawa had originally devised to entertain her children. More than 250 participants, ranging from ages three to ninety, had been invited to make the panoramas.

With regard to her many public works, of which these two are among the most prominent and beloved examples, Asawa stated: “When you work out in the public, it’s just not the place to express yourself. You need to do something that will allow the people who see it to respond to it.”4 She believed that the many abstract sculptures placed around American cities in the late 1960s and 1970s were not getting the reception she would have wanted for her own public works. Appealing to a broader audience, she chose content that she considered more popular and, when possible, engaged the public in the making of her work. Discussing the inclusive creative process for the Hyatt fountain, Asawa said:

Since we have no real folk art or craft tradition any more in this country, this kind of activity has to be recreated to bring families and communities together. . . . When the [Hyatt] fountain came along I thought it was a great opportunity to show how group skills could be used to make something that people usually think of as high art—one product from one person’s mind and hands. . . . It is the idea of bringing skills together that interests me. We see this in science, in the space program, but we have lost it in art.5

Asawa’s nonjudgmental approach to style—her embrace of both abstract and representational means—and her openness to group involvement, unusual at a time when most artists privileged an individualist way of working, may have been due in part to her extraordinary background. As an American-born woman of Japanese descent from a poor family, she faced prejudices and barriers but managed to “transform the many obstacles... into lessons learned” and to maintain a positive approach, availing herself of the possibilities that came her way.6

Asawa was born in Southern California in 1926 to Japanese immigrants who worked as truck farmers. They grew vegetables on eighty-five acres of leased land—at that time, Japanese immigrants were barred from American citizenship and the right to own land and transported the produce to market. Asawa was the fourth of seven children, all of whom had jobs in their home and on the farm. Saturdays were the best days of the week, she later recalled, because the children could skip their chores to attend Japanese school, where they learned language and culture. Particularly important were the calligraphy classes she took there, which were her first experience with a brush; the repetitious mark making and emphasis on unpainted areas of the page were lessons that stayed with her.

When Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor, life as she knew it quickly came to an end. In February 1942, her father was taken from their home to a labor camp; two months later, she, her mother, and siblings (except for one sister who was in Japan visiting relatives) were forced to leave their home and belongings behind and were placed in an internment camp at the Santa Anita racetrack, where they lived in the horse stalls for six months. Asawa, in descriptions of her time there, rarely mentioned the difficulties that must have existed; rather, she emphasized the fact that she had the opportunity to take art classes from Japanese artists who had worked at Walt Disney Studios. From them, she furthered her drawing skills.

After six months, Asawa and her family—still without her father—were moved to the Rohwer Relocation camp in Arkansas. Again, Asawa, who by then was showing her artistic talent, took art classes from teachers she admired. Upon graduating high school in 1943, she was allowed to attend a midwestern college. She chose to enroll in Milwaukee State Teachers College, the school with the cheapest tuition that she could find; there she planned to get a degree to teach art. In the summer of 1945, she went to Mexico to see and learn about Mexican mural painters Diego Rivera and José Orozco. She studied fresco painting and observed Orozco making a large mural (which undoubtedly influenced her later public works). The trip was also important for Asawa because she was able to observe the lifestyles of working artists; she took a class from Clara Porset, a Cuban modern furniture designer, from whom she learned about Josef and Anni Albers, Bauhaus artists who had also spent time in Mexico and were teaching at an innovative and progressive North Carolina school called Black Mountain College.

Asawa returned to Milwaukee to finish her degree only to find that, because of anti-Japanese sentiment, she could not get a practice teaching position, a requirement for graduation. Two artist friends—Elaine Schmitt, whom Asawa had met in college, and Ray Johnson, whom Asawa knew through Schmitt—had been speaking to her about their experiences at Black Mountain even before she went to Mexico; they encouraged her to join them at the school. So Asawa arrived for the 1946 summer program at Black Mountain and stayed through the spring of 1949, with help from an anonymous source who contributed to her tuition. From Asawa’s own accounts, her experience at Black Mountain was transformative in every way. In a statement from 1989, Asawa wrote, “It was in college that I experienced for the first time the feeling of being an individual, a minority of one.” It was at Black Mountain that she found her brain, as she put it, and was encouraged to have opinions that did not necessarily correspond to any received notions of loyalty to family, ethnicity, or gender.7 It was also at Black Mountain that Asawa decided to become an artist rather than an art teacher, and it was there that she met her future husband, Albert Lanier, who would become her partner in all parts of life, contributing to the creative management and intermingling of family and work.

Black Mountain, founded in 1933 in western North Carolina, “incorporated characteristics of a summer camp, a rural work school, an art colony, a religious retreat, a pioneering village, and the liberal arts college it was intended to be.”8 It was a progressive school meant to educate the whole person through academic courses as well as lessons in communal living. Farm work and maintenance were part of the curriculum; there were no grades and the relationship between the faculty and the students was close, with the students participating in school governance. The summer sessions especially became something like an art colony, attracting a number of artists as teachers and students who were or would become well known, including, among others, Josef and Anni Albers, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Buckminster Fuller, Jacob Lawrence, and Robert Rauschenberg, all of whom were there at the same time as Asawa.

It was Josef Albers—a teacher from the renowned Bauhaus school in Germany who had come to the United States in 1933 to form Black Mountain’s visual arts program—who had the biggest influence on Asawa. Arriving at Black Mountain for the 1946 summer program, Asawa had planned to sign up for Anni Albers’s weaving class but Albers informed her that a summer was too short a time to learn to weave and recommended her husband’s introductory courses in design and color instead. It was the lessons learned in these classes, which Asawa took several times, that laid the groundwork for her encompassing approach to art and life. In a 1963 talk she gave on Albers, with whom she remained friends until the end of his life, she explained the focus of his teaching.9 He advised his students to leave all stylistic prejudices behind, learning to see forms and materials in a fresh, authentic way. Self-expression was not the goal; he wanted his students to observe carefully as a way to see more acutely and cultivate imagination. He emphasized the acquisition of a skilled hand, acquired through repetitive exercises and the development of technique. And he encouraged the use of simple materials like paper, string, wire, leaves, or twigs—whatever was available—and taught them to allow the material to express itself. He promoted experimentation even if it brought on failures, and expected his students to hear and learn from others, to respond to their thoughts and criticisms.

Asawa’s paintings and watercolors from her years at Black Mountain reflect Albers’s teaching while simultaneously showing evidence of those elements that distinguish her work. Untitled (BMC.76, BMC Laundry Stamp) (c. 1948–1949), for example, employs repetition and simple materials. Using a stamp meant to mark the laundry (Asawa was working in the school laundry at the time), Asawa printed several columns formed by the initials “BMC.” The initials themselves lose meaning as they are positioned upside down, backwards, and overlapping; the undulating rows take on the appearance of flowing fabric. In later works, made after leaving Black Mountain, Asawa used stamps made from potatoes and apples, cutting designs into the fruit or vegetable and printing out repetitive but whimsical overall patterns. In paintings such as Untitled (BMC.95, In and Out) (c. 1948–1949), a contrast of colors in interlocking chevrons recalls Josef Albers’s own efforts to reveal how the appearance of color and shape changes in relation to context. Similarly, Untitled (BMC.83, Dogwood Leaves) (c. 1948–1949) has balloon-like shapes, attached and interlocking; it is likely a study from an Albers class, but is more organic and quirky than his work. Its design predicts the forms of Asawa’s sculpture, which she was starting to develop around the same time.

It was at Black Mountain in the summer of 1948 that Asawa met Fuller. His teaching reinforced the organic thread in her work, initially derived from her lifelong involvement with farming and gardening. Although Asawa admitted that she didn’t always comprehend his theories, she and Lanier became good friends with the inventor; besides writing recommendations for her, Fuller designed her wedding ring. She also attended many of his famously long lectures; in a later one, in 1977, she took pages of notes that were also filled with wonderful doodles and sketches of Fuller on stage. His core ideas lay in his belief that a close study of nature could reveal simple, geometric principles underlying the universe and help invent ways to do more with less in industrial design, architecture, and social planning. He believed in the interrelatedness of things and the necessity of collaboration, and that progress could be achieved with good design. He was an early conservationist and proponent of affordable housing. Asawa also cited the influence of his experimental approach—starting small and simple, building upon failure, and working up to larger more complicated form.10 It should be noted too that Fuller’s transparent geodesic dome models have an aesthetic resemblance to some of Asawa’s looped-wire sculptures.

Asawa began making her wire works in 1947 while she was still at Black Mountain. That summer she had made another trip to Mexico, where she had learned to make wire baskets from a craftsman in Toluca. Back at Black Mountain, she made baskets that were both functional and wonderfully shaped; she gifted one to Anni Albers, who admired its looped structure and used it to hold her annual holiday cards.11 Asawa soon adapted her technique, making sculptures that were not functional but retained some sense of the vessel-like shapes of the baskets. Asawa stated, “Working in wire was an outgrowth of my interest in drawing. The sculptures became three-dimensional drawings.”12 Drawings like Untitled (BMC.128, Study of Triangles) (c. 1948–1949) and Untitled (BMC.121, Exercise in Color Vibration and Figure Background) (c. 1948–1949), both originally owned by the Alberses, make it clear what Asawa meant. The former’s linear, triangular patterning, as well as the play of space between full and empty forms, and the latter’s hanging, rounded shapes parallel similar ideas played out in three dimensions in Untitled (S.264, Hanging Two-Lobed Continuous Form) (1949), one of her first hanging, closed-form wire sculptures. Over the next several decades, Asawa continued to experiment with this material; it became central to what she once referred to as her most “serious” art, the paintings, drawings, and sculptures she made to satisfy her own aesthetic concerns.13

The technique was a simple one. Asawa explained, “The crochet loop is like an e. You begin by looping a wire around a wooden dowel, then making a string of e’s, always making the same e loop. You can make different size loops depending on the weight of the wire and the size of the dowel. You can loop tight and narrow or more open and loose. The materials are simple. You can use bailing wire, copper wire, brass wire. We used whatever we had.” Explaining how the forms evolved, she continued, “The shape comes out working with the wire. You don’t think ahead of time, this is what I want. You work on it as you go along.”14 But the process was sometimes difficult—Asawa wrapped her fingers to protect against cuts—and it was repetitive and time-consuming.

Untitled (S.264) is small and somewhat tentative. Asawa quickly expanded her scale and the complexity of her forms. The continuous lobed works could have as many as eight or nine lobes, typically stretching to nine or ten feet (the largest is twenty-one feet), as in Untitled (S.154, Hanging Nine-Lobed, Single-Layered Continuous Form) (c. 1958). She also invented ways to interlock shapes, occasionally making asymmetrical configurations such as Untitled (S.089, Hanging Asymmetrical Twelve Interlocking Bubbles) (1957), and began enclosing globes within globes using a single strand of wire. Untitled (S.453, Hanging Three-Lobed, Three-Layered Continuous Form within a Form) (c. 1957–1959) is a particularly complicated work; its three tiers each contain three globes nestled within each other, all made from a continuous surface. Asawa continued to devise different shapes like the cones hanging one atop another in Untitled (S.030, Hanging Eight Separate Cones Suspended through Their Centers) (c. 1952) or the billowing, undulating pattern of Untitled (S.039, Hanging Five Spiraling Columns of Open Windows) (c. 1959-1960). She also experimented with different wires, using copper, brass, iron, and occasionally gold-filled sometimes interweaving more than one type in a single sculpture— to vary surface and reflectivity. The width and flexibility of the wire also helped determine the scale; the gold ones, for example, are small, delicate, and glittery. On one occasion, Untitled (S.335, Hanging Four-and-a-Half Open Hyperbolic Shapes that Penetrate Each Other) (c. 1954), she experimented with painting the wire white but was dissatisfied with the result and repainted it black, perhaps to restore its linear quality.

In 1962, Asawa devised a new way of working with wire. After friends presented her with the skeletal remains of a desert plant that they thought she might be interested in drawing, she decided to replicate it in wire to better understand its form. This led to what Asawa referred to as her tied-wire works; tree-like sculptures that evolved from many strands of wire tied together centrally but divided into radiating branches, such as Untitled (S.184, Hanging Tied-Wire, Multi-Branched Form Based on Nature) (c. 1962). These works, too, became more complicated in time, as exemplified by Untitled (S.070, Wall Mounted Tied-Wire, Open-Center, Five-Branched Form Based on Nature) (1988), a wall mounted sculpture with a central five-pointed star spreading out geometrically into spidery branches. In these and other tied-wire works, she continued to experiment with various configurations of form, types of wire, and patinas.

Starting during her years at Black Mountain, Asawa’s work attracted interest within the art world and beyond. A 1948 Time magazine review of an exhibition of the best student work from twenty-five top US art schools singled out one of Asawa’s paintings as “the exhibition’s high point of originality.”15 By the 1950s she was showing in New York, with three solo exhibitions at Peridot Gallery (1954, 1956, 1958) that led to reviews in The New York Times, ARTnews, and Arts Digest, among other publications; her work was also featured in Vogue and Domus around this time. The exposure led to her inclusion in the Bienal de São Paulo (1955), and in shows at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1955, 1956, 1958), and The Museum of Modern Art, New York (1959). A number of notable collectors bought her work, including the architect Philip Johnson, New York governor Nelson Rockefeller, and writer Jean Lipman (who later donated her work to the Whitney). Untitled (S.693, Hanging Six-Lobed, Two-Part Complex Form within a Form with One Suspended Sphere in the Top Lobe) (c. 1956) was purchased from the 1956 show at Peridot by industrial designer Francis Blod and his wife Peggy for their midcentury, modernist home in Connecticut.

These achievements marked a positive beginning for a commercial career, but as has been pointed out by several writers, the reviews and published context in which her work was presented contain overtones of gender and racial prejudice.16 Eleanor C. Munro suggested Asawa’s sculptures were “domestic,” not “monumental” works, best used “for home decoration.”17 Dore Ashton described the works as “airy,” “buoyant,” “cheerful,” and “graceful,” but ultimately dismissed them as “only decorative objects in space.”18 Others compared her sculptures to craft, usually Japanese basket weaving, in such a way that overlooked the work’s originality and significance. In one egregious example—in a mostly positive article professing the importance of two artists of Japanese descent, Isamu Noguchi and Asawa—the reviewer introduced the former as “a leading American sculptor” and the latter as “a San Francisco housewife and mother of three.”19 These perceptions were reinforced in fashion shoots where the sculptures were used as foils for models, who in some cases actually embraced the art.

When Asawa was asked why she pulled back from exhibiting her work in New York’s galleries, she said it was because the sculptures were often badly damaged when they returned after the exhibitions, and she didn’t want to acquiesce to commercial demands.20 But one can’t help but think that the reception had something to do with it too. Her work was not always being seen as art. In 1954, after a beautiful and accurate description of the wire works as “tantalizing creations, delightful to watch and wonder at, gracefully proportioned and balanced, delicate yet subtle and strong,” the reviewer finished by saying, “but they are such novel innovations that one is obliged for the present to treat them as phenomena rather than art.”21

In some ways, Asawa’s work (and she herself as an artist) did not fit the existing norms and conventions of the time; the novelty of her work could not be accommodated. While her sculptures might seem to have much in common with Noguchi’s lamps and Alexander Calder’s mobiles, for example, they are distinguished by their non-functionality (in the case of the lamps), greater abstraction and spatial immediacy, and the evidence of the handmade process by which they are made. Her work also shares aesthetic concerns with other artists working in wire like Ibram Lassaw and Richard Lippold, who also transformed linear patterns into three-dimensional sculptures. Lippold, a friend from Black Mountain, especially shared Asawa’s interest in industrial material and the effects of light on metal. These two artists were rooted in the era’s prevalent geometric traditions—Lassaw in cubism, Lippold in Bauhaus industrial design. Asawa, for her part, was more interested in organic forms, suggesting further associations with the work of Hans Arp and Constantin Brancusi. The repetitive columnar pattern of some of her hanging wire works recalls that of Brancusi’s Endless Column. In her use of humble materials and transparent forms, however, Asawa’s work stands apart from Arp’s and Brancusi’s more conventional use of stone and wood to make heroic, monumental sculptures.

Though she withdrew from the New York art world from the 1960s on, Asawa continued to have an active career. In 1970, her sculpture Untitled (S.108, Hanging Six-Lobed, Multi-Layered Interlocking Continuous Form within a Form with Spheres in the Second and Third Lobes) (c. 1970) traveled to Osaka, Japan, along with works by Richard Diebenkorn and other California artists for the San Francisco Art Commission’s presentation at Expo ’70, a world’s fair. Then in 1973, the San Francisco Museum of Art mounted her first retrospective exhibition. She also completed many public commissions, including Origami Fountains (PC.006), two fountains for Buchanan Mall in San Francisco’s Japantown (1975-1976, refabricated 1999) and San Francisco State University’s Garden of Remembrance (PC.012) (2000-2002), commemorating Americans of Japanese ancestry interned during World War II. But it was not until recent years that Asawa’s most innovative work has come to national and international attention.

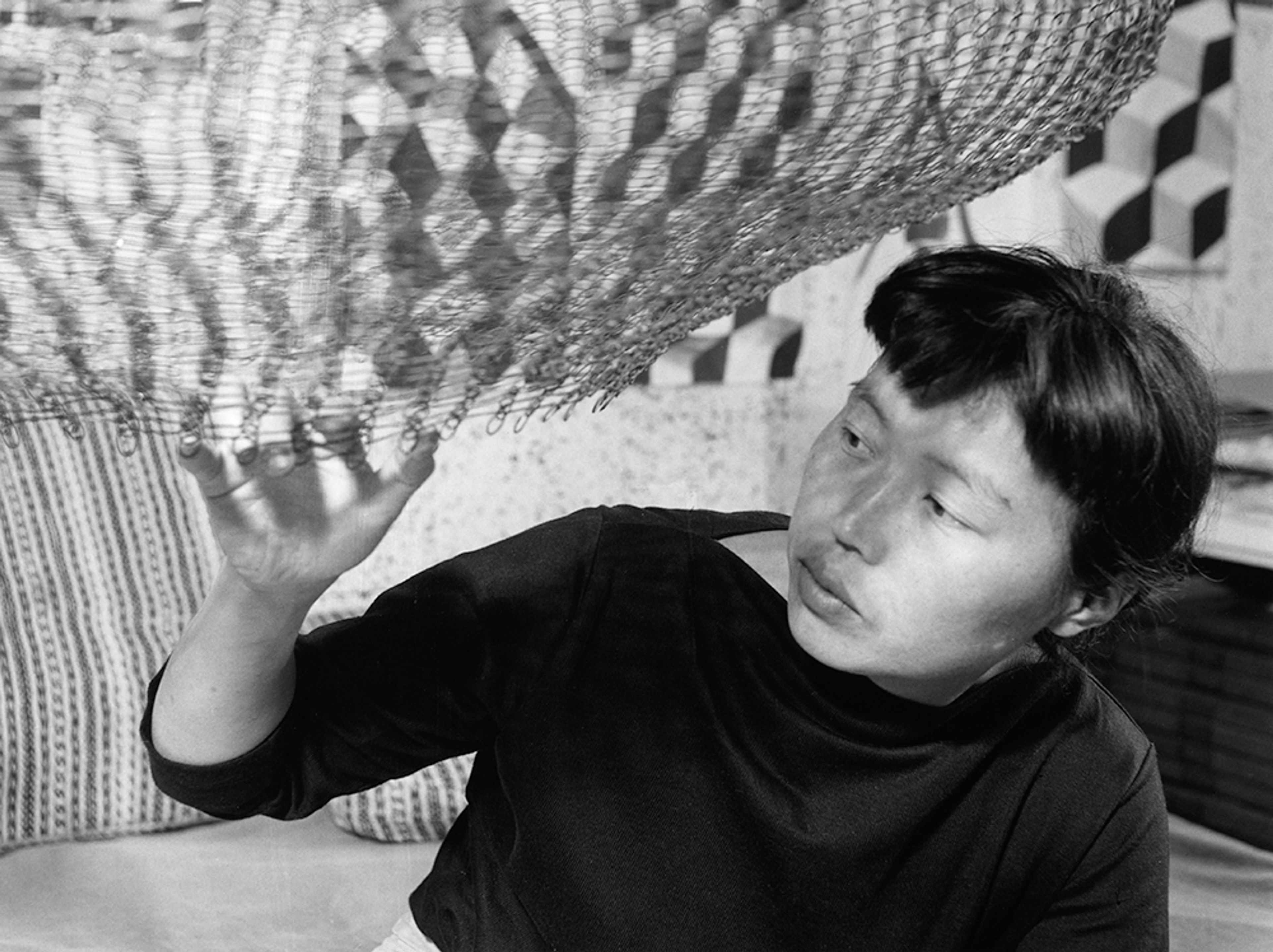

In 2006, she had a major retrospective at the de Young Museum, San Francisco. More recently, her art has been included in many themed exhibitions, prompting a recontextualization and more comprehensive understanding of Asawa’s work. Helen Molesworth, for example, in an in-depth consideration of the influence of Black Mountain on art made in the late 1950s and 1960s, directs attention to the anthropomorphism in Asawa’s forms. She suggests that Asawa’s participation in Merce Cunningham’s dance class at Black Mountain helped her learn “about the expressive capacity of the human body.”22 John Yau has associated her sculptures with the female body;23 their vessel-like forms containing shapes seem to vaguely refer to birth and the continuity of life. The sculptures’ figural presence is reinforced in wonderful pictures taken by photographer Imogen Cunningham, Asawa’s close friend, showing the artist in her home surrounded by her children and work. In comparison to the staged, sterile quality of the fashion shots mentioned above, these photos show the works as intimate and sensual. These qualities suggest comparisons to Louise Bourgeois’s Personages of the late 1940s and early 1950s, which, like Asawa’s wire forms, have a figural presence that is more elemental and primal than traditional idealized representations of the female nude.24

Connections have also been made to the weavings of Anni Albers and Lenore Tawney, recognizing and appreciating the ways in which process contributes to content, evoking elements such as time and continuity. Similarly, the materiality of Asawa’s transparent hanging wire works compares to that of dangling string pieces by Eva Hesse, the artist most often credited as challenging the more aggressive, heroic gestures of her male colleagues.

Affinities continue to abound. Suffice it to say, the appreciation and understanding of her work now lives up to Buckminster Fuller’s estimation of her talents. Just as poignant is the example Asawa set as an artist, teacher, and citizen. When asked in 1990 about her wish for her legacy, she responded: “the ability to adjust, to adapt, to make something out of nothing.”25

Notes

This essay was originally published in Ruth Asawa. Exh. Cat. (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2018).

1. R. Buckminster Fuller, letter to John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, September 30, 1971, Ruth Asawa Papers (M1585), Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries.

2. Fuller, text on Ruth Asawa, January 18, 1982, Ruth Asawa Papers (M1585).

3. The information about awards made in the 1971–1972 grant cycle comes from this webpage: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Guggenheim_Fellowships_awarded_in_1972 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Guggenheim_Fellowships_awarded_in_1972).

4. Ruth Asawa, in Katie Simon, “A Conversation with Ruth Asawa, Artist,” Artweek (August 1995), p. 18.

5. Asawa, as quoted in Sally B. Woodbridge, Ruth Asawa’s San Francisco Fountain, Hyatt on Union Square. Brochure (San Francisco, 1973), p. 5.

6. John Yau, “Ruth Asawa: Shifting the Terms of Sculpture,” in Ruth Asawa: Objects & Apparitions. Exh. cat. (New York: Christie’s, 2013), p. 5.

7. Asawa, as quoted in Mary Emma Harris, “Black Mountain College,” in The Sculpture of Ruth Asawa: Contours in the Air, ed. Daniell Cornell. Exh. cat. (San Francisco and Berkeley: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and University of California Press, 2006), p. 45; and statement for San Francisco Art Institute panel discussion, April 7, 1989, Ruth Asawa Papers (M1585).

8. Harris, “Black Mountain College,” p. 43.

9. Notes for a talk on her experiences as a student of Josef Albers that Asawa gave at the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1963 on the occasion of Albers’s retrospective there. Ruth Asawa Papers (M1585).

10. See Ruth Asawa, interview between P3 [P3 Group, Tokyo] and Ruth Asawa, 1989, Ruth Asawa Papers (M1585).

11. See Nicholas Fox Weber, “Ruth Asawa and Anni and Josef Albers: Splendid Soulmates,” in Ruth Asawa: Objects & Apparitions, p. 32.

12. Asawa often spoke about how her interest in drawing led to the wire sculptures. This particular quotation is from a statement in Japanese-American Women Artists: Fiber & Metal. Exh. brochure (Olympia, Washington: Evergreen Galleries, Evergreen State College, 1984).

13. Asawa, statement, 1991, Ruth Asawa Papers (M1585). This is a manuscript for what is probably a published statement in a catalogue.

14. Asawa, as quoted in Jacqueline Hoefer, “Ruth Asawa: A Working Life,” in The Sculpture of Ruth Asawa: Contours in the Air, p. 16.

15. “Tomorrow’s Artists,” Time (August 16, 1948), p. 45.

16. See especially Emily K. Doman Jennings, “Critiquing the Critique: Ruth Asawa’s Early Reception,” in The Sculpture of Ruth Asawa: Contours in the Air, pp. 128–137.

17. Eleanor C. Munro, “Globe within a Cup within a Sphere,” ARTnews (April 1956), p. 26.

18. Dore Ashton, “Displays at the Peridot, ACA and Heller,” The New York Times (March 14, 1956), p. 36.

19. “Eastern Yeast,” Time (January 10, 1955), p. 54.

20. Addie Lanier, in conversation with the author, June 2017.

21. Martica Sawin, “Ruth Asawa,” Arts Digest (December 15, 1954), p. 22.

22. Helen Molesworth, Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957. Exh. cat. Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2015), p. 366.

23. Yau, “Ruth Asawa: Shifting the Terms of Sculpture,” p. 14.

24. See Jonathan Laib, Ruth Asawa: Objects & Apparitions, p. 25.

25. Asawa, as quoted in “Ruth Asawa: Artist and Educator,” Strength and Diversity: Japanese American Women, 1885 to 1990, Classroom Study Guide, p. 20, published by the National Japanese American Historical Society to accompany the exhibition of the same title at The Oakland Museum, California, 1990. Ruth Asawa Papers (M1585).

魯斯·阿薩瓦:從無到有

文/ 蒂芙尼·貝爾

觀看一組魯斯·阿薩瓦的金屬絲線雕塑懸掛在一起,是一種驚奇而喜悅的體驗。這些作品的形式、形狀和材料具有極簡的特性,然而由於創作過程極為耗費精力,而且當人們觀察它們的相互關聯時會發生感知上的變化,這些雕塑促使人們去持續地觀看。阿薩瓦的許多懸吊式雕塑都具有透明的、環形金屬絲線的表面,以及起伏的、球狀的形態;它們是有機而感性的。有些作品鏤空、具空氣感;而在另一些作品中,雕塑的外部形狀圍裹住其他形狀,使得某些區域變得深沈晦暗,幾乎不可見。這些層次豐富的作品,可以由單根連續的金屬絲線構成,它以環狀的方式纏繞,使得其內部無縫地漸變至外部。當這些作品成組地懸掛時,其視覺複雜性更甚;而當觀眾繞著作品走,重疊的形狀又會引發縱深及扭動形態的不斷變化。變幻莫測的陰影,更增添了一重維度。

1971年,極富盛名的二十世紀發明家、遠見卓識的巴克敏斯特·富勒(Buckminster Fuller)為阿薩瓦申請古根海姆基金會的年度獎金項目寫過一封推薦信。富勒在信中提到,他為各種候選人撰寫推薦信已有四十三年,繼而寫道:「我毫不猶豫、毫無保留地認為,魯斯·阿薩瓦是我所認識的最具天賦、高產、原創性的藝術家。這個說法包括了本世紀諸多聲譽卓著的『偉人』。」 【僅舉兩位「偉人」為例:富勒與亞歷山大·考爾德(Alexander Calder)和野口勇(Isamu Noguchi)均為富勒的親密好友。】他提到了她的環形金屬絲線雕塑。自1940年代晚期他和阿薩瓦同在北卡羅來納州的黑山學院起,富勒便對她的作品熟稔有加,而阿薩瓦也正是以這些雕塑作品申請的獎助金。富勒繼續寫道,阿薩瓦是幾個孩子的母親,在將革新的藝術課程引入舊金山公立學校方面發揮了主導作用;他還提到,阿薩瓦與她的丈夫、身為建築師的阿爾伯特·拉尼爾(Albert Lanier)一起,將舊金山一處老舊的房子改造成了一個「迷人而鼓舞人心」的家。【1】

富勒認為每個孩子一出生就是一位「觀念的天才」,他還提倡用多學科的方式去創造更美好的社會,因此我們不難理解,他會因為阿薩瓦廣泛地參與各種創意性和社會性的活動而推薦她。【2】以我們現在的角度來看,阿薩瓦也因其非凡的成就脫穎而出。除了在50多年裏創作了大量革新、抽象的雕塑、繪畫及版畫之外,她還和拉尼爾倆人在自己打造的家裏養育了六個孩子。同樣值得一提的是,他們在後院精心打理的花園綠意盎然、碩果累累。此外,阿薩瓦在舊金山各所學校的工作非常成功,以至於一所本地的公共藝術學校如今以她的名字命名。她還參加了數個社區委員會以及加州藝術委員會(California Arts Council)和美國國家藝術基金會(National Endowment for the Arts),並且是舊金山藝術博物館的董事。她創作了不少公共藝術作品,還組織了眾多參與性的社群活動,以藝術作為方式,激發年齡各異的社區鄰居們的意識思考及創造力。

但在1971年,一心一意專注於個體自身的藝術創作在那個時代被高估了,所以古根海姆基金會的評審們也許對信中提到的阿薩瓦的孩子以及她在公立學校的工作都不感興趣。那一年,基金會純藝術門類的獎金共頒發給了22位藝術家——其中只有一位是女性。【3】 阿薩瓦未能獲得資助。

當時,阿薩瓦可能因為她的公共委任項目而在當地廣為人知。她最早的這類作品便是基於她的金屬絲線雕塑,但在1968年,阿薩瓦完成了為舊金山吉拉德利廣場(Ghirardelli Square)創作的《安德烈婭》(Andrea,圖PC.002),這是一片對歷史悠久的「吉拉德利巧克力工廠」進行重新開發的濱水區。阿薩瓦並沒有按照項目景觀建築師的提議運用她的抽象樣式,而是創作了一幅夢幻般的場景:兩個坐著的美人魚——其中之一正在哺育一個嬰兒——周圍環繞著烏龜、青蛙、睡蓮。1973年,她完成了作品《舊金山噴泉》(圖PC.004),41塊青銅鑄板圍繞著一個圓形水池,位於聯合廣場凱悅酒店外的廣場。每塊銅板上都包含了當地的歷史地標和風景,它們最初是用「烘焙黏土」雕刻而成的——阿薩瓦為了娛樂孩子們而發明的一種類似於面包面團的廉價材料。從3歲到90歲的250多位參與者,受邀參與了這幅全景式作品的創作。

這兩件是她諸多公共項目中最為突出也廣受喜愛的作品,阿薩瓦曾就此表示:「當你在公共場所工作時,那並不是你表達自我的最佳場所。你需要做一些讓看到它的人能夠做出回應的事。」【4】她相信,許多1960年代晚期和1970年代放置在美國城市裏的抽象雕塑所得到的反響,與她對自己公共作品的期待並不相符。為了吸引更廣泛的觀眾,她選擇的是她認為更受歡迎的內容,並在可能的情況下讓公眾能深入參與她作品的創作。在論及凱悅酒店噴泉作品的創作過程時,阿薩瓦曾經說道:

有鑒於我們國家已經不再擁有真正的民間藝術或手工藝的傳統,因此這樣的活動必須被重新創建,以將家庭和社群團結在一起……當(凱悅酒店)噴泉出現時,我覺得這是一個很好的機會,用以展示如何利用團隊技能製作出人們通常認為的高雅藝術作品——一件出自一個人的頭腦及雙手的產物……我感興趣的是將各種技能結合起來。我們在科學領域、太空計劃中都看到了這一點,卻在藝術中失去了它。【5】

阿薩瓦在風格上的創作方式是不帶偏見的——她采納抽象及具象的創作——對團體參與的態度也保持開放,這在大多數藝術家都偏愛個人主義創作方式的時代是非比尋常的,這可能部分地歸功於她不同尋常的背景。作為一位出生於美國、家庭貧窮的日裔女性,她所面臨的是種種偏見與重重壁壘,但她成功地「將諸多障礙……轉化成了經驗教訓」,並且保持著積極的態度,把握一切可能的機會。【6】

阿薩瓦1926年出生於南加州,父母是從事卡車農民的日本移民。他們在85英畝的租地上種植蔬菜——在當時,日本移民們被禁止獲取美國公民身份,也無權擁有自己的土地,不能自行將農作物運送到市場。她後來回憶,星期六是一周裏最美好的日子,因為孩子們可以不用做雜務零工,而是去日本學校學習語言和文化。對她而言尤為重要的是在日本學校上的書法課,她第一次接觸筆刷;反復的筆痕以及對頁面留白的強調,都是讓她受益匪淺的課程。

日軍飛機轟炸珍珠港時,她所熟悉的生活迅速終結了。1942年2月,她的父親被從家裏帶去了勞改營,兩個月後,她和母親及兄弟姐妹(除了一個正在日本探親的姐姐)被迫離開他們的家和財產,被安置在位於聖塔安尼塔賽馬場的一處拘留營,在馬廄中住了六個月。在描述她在那裏度過的時間時,阿薩瓦很少提及必然存在的種種困難,相反,她強調的是自己有機會向曾在迪士尼工作室工作的日本藝術家們學習藝術。阿薩瓦的畫畫技巧因此得到了提升。

六個月後,阿薩瓦和她的家人(除了父親)被轉移到阿肯薩斯州的羅爾韋安置營(Rohwer Relocation camp)。當時已展露出藝術天賦的阿薩瓦再次跟隨她仰慕的老師們學習藝術。1943年高中畢業後,她被允許進入中西部的一所大學就讀。她選擇了密爾沃基州立師範學院——她能找到的學費最便宜的一所學校,並且計劃在那裏取得藝術師範專業的學位。1945年夏天,她前往墨西哥拜訪並學習了解墨西哥壁畫畫家迭戈·里維拉(Diego Rivera)和何塞·奧羅斯科(José Orozco)。她學習了壁畫繪畫,並且觀察奧羅斯科創作了一件大幅壁畫(這些無疑影響了她後來的公共作品)。這趟旅行對阿薩瓦來說實為重要,因為她得以觀察其他創作中的藝術家們的生活方式,她上了一門古巴現代家具設計師克拉拉·波塞特(Clara Porset)的課程,從波塞特那裏得知了約瑟夫和安妮·阿爾伯斯(Josef and Anni Albers)——兩位也曾在墨西哥待過一段時間的包豪斯藝術家,他們當時正在北卡羅來納州革新性的黑山學院任教。

阿薩瓦返回密爾沃基以期完成學位,但由於當時的反日情緒,她無法找到擔任實習老師的職位——而這是滿足畢業資格的條件。阿薩瓦在大學時認識的兩位藝術家朋友——伊萊恩·施密特(Elaine Schmitt)、以及通過施密特認識的雷·約翰遜(Ray Johnson)——早在她去墨西哥之前就在對她講述過他們在黑山學院的經歷,也鼓勵她一起加入。在一位匿名人士的幫助下,阿薩瓦獲得了學費資助,她前往黑山學院參加1946年的夏季項目,並在那裏一直待到了1949年春天。根據阿薩瓦自述,她在黑山學院的經歷對她產生了全方位的影響。阿薩瓦在1989年這樣寫道:「在學校,我第一次體會到了身為一個個體、一名少數族裔的個體的感受。」 正如她所說,她在黑山學院找到了自己思考的頭腦,並敢於發表有悖於家庭、種族或性別之既定觀念的觀點。【7】 同樣是在黑山學院,阿薩瓦決定要成為一位藝術家而不是一位藝術教師;也是在那裏,她認識了自己未來的丈夫阿爾伯特·拉尼爾,拉尼爾在日後成為了她生活裏方方面面的伴侶和搭檔,為她創造性地管理並兼顧家庭與工作做出了貢獻。

1933年創立於北卡羅來納州西部的黑山學院「致力於成為一所文理學院,同時又融合了夏令營、鄉村工讀學校、藝術聚居區、宗教靜修所、先鋒試驗村落的種種特點」。【8】 這是一所積極進取的學校,旨在通過學術課程以及共享社群的生活經驗來全面培育學生。在那裏,農場的勞動和維護是課程的一部分,沒有考試評分體系,師生關系融洽而密切,並且由學生參與學校的管理工作。其夏季項目,尤其發展形成了一種藝術聚落,吸引了許多老師和學生前來,不乏一些當時或日後著名的藝術家,包括:約瑟夫和安妮·阿爾伯斯、約翰·凱奇(John Cage)、默西·坎寧安(Merce Cunningham)、威廉和伊蓮·德庫寧(Willem and Elaine de Kooning)、巴克敏斯特·富勒、雅各布·勞倫斯(Jacob Lawrence)以及羅伯特·勞申伯格(Robert Rauschenberg)等,他們與阿薩瓦在黑山學院的時間都有交集。

對阿薩瓦影響最大的是約瑟夫·阿爾伯斯——一位來自德國的著名包豪斯老師,他1933年移居美國後來到了黑山學院的視覺藝術學院。1946年夏天,阿薩瓦因夏季項目來到黑山學院,計劃上安妮·阿爾伯斯的編織課。但阿爾伯斯告訴她,要學習編織,一個夏天遠遠不夠,轉而推薦她去上自己丈夫有關設計和色彩的入門課程。這些課阿薩瓦上了好幾次,正是從中所學到的內容,為她對藝術和生活的包容態度奠定了基礎。她直到老師去世前都一直與他保持著友誼;1963年,她在一場有關阿爾伯斯的講座中闡釋了他教學的重點。【9】他建議學生們拋開所有有關風格的偏見,學著以嶄新、原真的方式去觀看形式和材料。自我表達並不是目的,他想讓學生們通過仔細觀察的方式去更敏銳地觀看並且培養自己的想象力。他強調通過反復的練習和技巧的發展來獲得嫻熟的手藝。此外,他鼓勵學生們使用簡單的材料,如紙、繩子、鐵絲、樹葉或樹枝等任何手頭現成的材料,教導他們讓材料來表達自己。他鼓勵學生們進行試驗,哪怕會面臨諸多失敗,他希望他的學生們能夠聽取他人意見、向他人學習,並且對他們的想法及評判做出回應。

阿薩瓦在黑山學院期間創作的繪畫和水彩作品,是對阿爾伯斯教學的反映,同時也體現了使她作品與眾不同的種種元素。比如,《無題》(BMC.76,BMC洗衣店印章,約1948-1949)采用了重復的手法及簡單的材料。她使用原本用於標記不同衣物的印章作為材料(阿薩瓦當時在學校的洗衣房工作),羅列出好幾排由首字母縮寫構成的「BMC」。顛倒、反置和重疊的排布,使得這幾個首字母丟失了原本的含義,而畫面起伏的線條則呈現出流動如織物般的外觀。在她離開黑山學院之後創作的晚期作品中,阿薩瓦使用馬鈴薯和蘋果作為印章,她在這些蔬菜水果上印刻出圖案,隨後列印出重復但異想天開的整體。在類似《無題》(BMC.95,進進出出,約1948-1949)的繪畫中,相互交錯的人字形對比色讓人想到約瑟夫·阿爾伯斯自己試圖揭示顏色與形狀之外觀如何隨環境而變化的努力。類似地,《無題》(BMC.83,山茱萸葉,約1948-1949)有著氣球般的形狀,它們相互聯結、交織,作品仿佛一幅出自阿爾伯斯課堂的習作,但相比他的作品則更為有機而詭異。作品的設計預示了阿薩瓦在同一時期開始創作的雕塑形態。

1948年夏天,阿薩瓦在黑山學院認識了富勒。他的教學增強了她作品中對有機線條的運用,而這些最初都源自阿薩瓦長久以來對農場和園藝的投入。儘管阿薩瓦承認自己並不總能理解富勒的理論,但她和拉尼爾還是和這位發明家成為了很好的朋友。除了為她寫推薦信之外,富勒還設計了阿薩瓦的結婚戒指。而她也曾參加富勒許多遠名昭著的長篇講座。在一次1977年的講座中,她就做了好幾頁筆記,裏面還用塗鴉和草圖刻畫了舞臺上的富勒。他的核心理念在於,他堅信對自然的深入研究可以揭示宇宙背後簡單的幾何原理,並且有助於在工業設計、建築、社會規劃中發明出以少博多的方法。他相信事物之間的相互關聯以及合作的必要性,並且相信通過良好的設計是可以取得進步的。他是一位早期的環保主義者,也是經濟適用房的支持者。阿薩瓦還提到他試驗性的創作方式所產生的影響——從微小、簡單的事物開始,在失敗的基礎上不斷建構,逐漸形成更大、更複雜的形態。【10】值得一提的是,富勒透明的測地線穹頂模型,與阿薩瓦的一些環形線雕塑在美學上有著相似之處。

1947年,還在黑山學院的阿薩瓦開始創作她的金屬絲線雕塑作品。那年夏天,她再次前往墨西哥,在托盧卡(Toluca)的一位手工藝人那裏學習用金屬線編織籃子。回到黑山學院後,她創作出許多既具功用性又形態優美的籃子,並將其中一個送給了安妮·阿爾伯斯,後者非常喜愛它的環形結構,並用它來盛放每年的節日賀卡。【11】阿薩瓦很快調整了她的技法,製作出一些不具備功能性但卻保留了籃子容器形狀的雕塑形態。阿薩瓦表示,「用金屬絲線來創作是從我對繪畫的興趣延伸而來的。這些雕塑成為三維的畫作。」【12】 作品《無題》(BMC.128,三角形的研究,約1948-1949)和《無題》(BMC.121,色彩振動與圖形背景的練習,約1948-1949)便清楚地表明了阿薩瓦的創作意圖,而這兩幅作品最初都由阿爾伯斯夫婦所收藏。前者的線性三角形圖案以及實心和空心形式之間有趣的空間構成,以及後者懸掛的圓形形狀,都相應地在三維空間中有著理念類似的展現。譬如《無題》(S.264,懸吊的兩瓣連續形態,1949),是她最早的懸吊式、封閉態的金屬絲線雕塑之一。在接下來的幾十年裏,阿薩瓦持續地試驗金屬絲線的材料,它在她曾經稱之為最「嚴肅」的藝術中占據著核心的位置,也是她為了滿足自己的美學追求而創作的繪畫、畫作及雕塑作品。【13】

技法其實很簡單。阿薩瓦解釋道,「鉤針形成的環狀就像一個字母『e』,你先拿一條金屬絲線纏繞在一根木釘上,之後再做出一串『e』,然後一直做相同的環狀的『e』字型。你可以依據金屬絲線的重量以及木釘的尺寸創作出大小不一的環狀結構。你可以繞得或緊或松,或是更開放且松散。材料很簡單。你可以用打捆用的鐵絲、銅線、黃銅線。我們手頭有什麽就用什麽。」 在解釋這些形態如何漸進衍變時,她繼續說道,「形狀是通過與金屬絲線的碰撞而產生的。你不用提前設想,這就是我想要的。你就這樣邊想邊做。」【14】 但這一創作過程時常很困難——阿薩瓦要把自己的手指包起來以免割傷——重復又耗時。

《無題》(S.264)尺幅小巧,而且多少顯出些試探的躊躇。阿薩瓦很快拓展了其作品的體量及其雕塑形態的複雜性。這些連續的、波瓣狀的作品可以包含多達八九個波瓣的形態,通常還會延展到9至10英尺(合約2.75到3米,最大的21英尺,合約6.4米),比如作品《無題》(S.154,懸吊的九瓣單層連續形態,約1958)。她還發明了相互鎖定的形態,偶爾還會創作不對稱的形態配置,如《無題》(S.089,懸吊的不對稱的十二個互鎖氣泡,1957),並開始使用單根金屬絲線將球體套入於球體之中。《無題》(S.453,懸吊的三瓣三層連續內嵌的形態,約1957-1959)就是一件尤為複雜的作品,其中的三層形態都包含著三個相互嵌套的球體,並且全部由連貫的表面製成。阿薩瓦持續地構想設計不同的形態,如《無題》(S.030,懸吊的通過其中心懸置的八個獨立圓錐體)中依次堆疊的圓錐體,或是《無題》(S.039,懸吊的五條旋轉的開放式窗戶狀的縱列,約1959-1960)中波浪般起伏的形態。她還用不同的金屬絲線進行試驗:銅、黃銅、鐵,偶爾還有註金的絲線;有時她還會在一件雕塑中交織使用多種金屬絲線——以使作品的表面和反射率產生變化。金屬絲線的寬度及柔韌度還有助於確定作品的體量,比如用註金絲線的那些總是小巧、精致,閃閃發光。在如作品《無題》(S.335,懸吊的四個半相互穿透的開放式雙曲線形態,約1954)的例子中,她嘗試將金屬絲線塗白,但對結果並不滿意,於是又重新塗成黑色,似乎這樣有助於保留材料的線性特質。

1962年,阿薩瓦發明了一種用金屬絲線創作的全新方式。朋友們送給她一株沙漠植物殘留下來的骨架,覺得她可能會有興趣描畫它,於是她決定用金屬絲線來復刻它,以便更好地理解它的形態。這隨之誕生了阿薩瓦所說的「捆紮線束」(tied-wire)作品,這些樹狀的雕塑由多股金屬絲線衍進而來,它們從中心綁束到一起,但分散出輻射狀的枝條——如《無題》(S.184,懸吊式捆紮線,基於自然的多杈分束形態,約1962)。這些作品也隨著時間的推移變得更加復雜,如作品《無題》(S.070,壁掛式捆紮線,中空,基於自然的五杈分束形態,1988),這件壁掛式的雕塑以一個五角星為中心,呈幾何形狀,散布出蜘蛛網狀的分支延伸。在這些作品以及其他捆紮線束的作品中,阿薩瓦持續用各種形式、金屬絲線的類型以及銅綠光澤等進行試驗。

自黑山學院期間開始,阿薩瓦的作品便吸引了藝術界內外的關註。1948年,《時代》雜誌在點評全美25所頂尖藝術院校的最佳學生作品展的文章中,突出評述了阿薩瓦的一幅繪畫,稱其為「展覽中最具原創性的作品」。【15】 到了1950年代,阿薩瓦開始在紐約展出作品,她在紐約橄欖石畫廊(Peridot Gallery)舉辦了三場個展(1954、1956、1958),並在《紐約時報》(The New York Times)、《藝術新聞》(ARTnews)、《藝術文摘》(Arts Digest)等雜誌上收獲了展評報道。她的作品在當時還被刊載於《時尚》(Vogue)和《Domus》等雜誌中。這些曝光讓阿薩瓦的作品被囊括於「聖保羅雙年展」(1955)、紐約惠特尼美國藝術博物館的諸多展覽(1955、1956、1958),以及紐約現代藝術博物館(MoMA)的展覽(1959)中。許多知名藏家都收藏了她的作品,包括建築師菲利普·約翰遜(Philip Johnson)、紐約州州長納爾遜·洛克菲勒(Nelson Rockefeller)以及作家基恩·利普曼(Jean Lipman,她後來將作品捐贈給了惠特尼博物館)。作品《無題》(S.693,懸吊式六瓣、兩部件復合形態,頂部內嵌一個懸掛的球體,約1956)在1956年橄欖石畫廊為阿薩瓦舉辦的個展上,被售於工業設計師弗朗西斯·布洛德(Francis Blod)和他的妻子佩姬(Peggy),作品呈現於他們位於康涅狄格州的中世紀現代主義住宅中。

這些成就標誌著阿薩瓦在商業上一個積極的開始,但是正如幾位作家所指出的那樣,探討其作品的不少展評和報道中飽含了與性別及族裔有關的偏見。【16】 埃莉諾·C·蒙羅(Eleanor C. Munro)認為,阿薩瓦的雕塑是「居家的」而非「紀念碑式的」作品,它們最適合「用於家庭裝飾」。【17】 多爾·阿什頓(Dore Ashton)則將這些作品描述為「輕盈」、「輕快」、「歡欣」而「優雅」的,但終究「只是空間中的裝飾性物件」。【18】其他人則將她的雕塑與手工藝做類比,他們通常會提及日本的編織工藝,從而忽視了作品的獨創性和重要性。有一個例子令人震驚——在一篇總體上對兩位日裔藝術家野口勇和阿薩瓦的重要性持正面態度的文章中,作者將前者稱為「美國重要的雕塑家」,而後者則是「一位舊金山的家庭主婦和三個孩子的母親」。【19】這些觀點在時尚雜誌的拍攝中也得到了固化強調——在其中,阿薩瓦的雕塑被用作模特的陪襯;在某些情形下,模特們甚至擁抱著藝術作品。

當阿薩瓦被問及她為何不再在紐約的畫廊展出作品時,她說因為這些雕塑在展覽結束被送回時常常嚴重受損,而她不想屈從於商業市場的需求。【20】但人們不禁會想,展覽的反響也與此有關。她的作品並不總被看作藝術。在1954年,有藝評人曾將她的金屬絲線作品描述為「引人入勝的創作,賞心悅目,比例勻稱優雅,細膩而微妙並且強大有力」,可話鋒一轉在最後評述道:「但它們是如此新穎的創作,以至於人們現在不得不將之視為現象,而非藝術」。【21】

在某些方面,阿薩瓦的作品(以及作為藝術家的本人)並不符合當時藝術界的既定規則和傳統,她作品新穎的特性無法為當時所接受。舉例而言,儘管她的雕塑似乎與野口勇的燈以及亞歷山大·考爾德的動態雕塑有諸多相似性,但它們(與燈相較)並不具實際功用性,而且更抽象、更有空間張力,也更強調手工製作的痕跡。她的作品與其他采用金屬絲線創作的藝術家有著相同的美學理念,比如伊布拉姆·拉索(Ibram Lassaw)和理查德·利波爾德(Richard Lippold),他們也將線性的圖案轉化為三維的雕塑。尤其是利波爾德,倆人在黑山學院就結下了友誼,同阿薩瓦一樣對工業材料以及光影作用於金屬之上的效果感興趣。這兩位藝術家都深受當時盛行的幾何性美學傳統的影響——拉索是立體主義,利波爾德則是包豪斯式的工業設計。對阿薩瓦而言,她更感興趣的是有機形態,與讓·阿爾普(Hans Arp)及康斯坦丁·布朗庫西(Constantin Brancusi)的作品更具關聯性。她的一些懸吊式金屬絲線作品有著重復的長條柱狀的圖案,讓人想到布朗庫西(Brancusi)的《無盡之柱》。然而,阿薩瓦的作品擅用質樸的材料及透明的形態,它們與阿爾普及布朗庫西的作品不同,後者常以傳統手法采用石頭和木頭來創作宏大的、紀念碑式的雕塑。

儘管阿薩瓦在1960年代淡出紐約藝術界,但她的職業生涯仍然非常活躍。1970年,她的雕塑《無題》(S.108,懸吊式六瓣多層互鎖連續形態,第二與第三瓣中內嵌球體,約1970)巡展至日本大阪,與理查德·迪本科恩(Richard Diebenkorn)等其他加州藝術家們的作品一起由舊金山藝術委員會選送參加1970年世博會。之後的1973年,舊金山藝術博物館為她組織了首場回顧展。她還完成了眾多公共藝術委任創作,包括《折紙噴泉》(PC.006)——她為舊金山日本城布坎南購物中心(Buchanan Mall)創作的兩件噴泉作品(1975-1976,於1999年重製),以及為舊金山州立大學所做的《紀念花園》(PC.012,2000-2002)——以紀念第二次世界大戰期間被拘留的日裔美國人。但直到近年來,阿薩瓦最具革新性的作品才獲得了美國和國際的關注。

2006年,阿薩瓦在舊金山笛揚博物館舉辦了一場重要的回顧展。近年,她的藝術創作還被囊括到諸多主題展覽中,促使人們重新審視並更全面地理解阿薩瓦的作品。比如,海倫·莫爾斯沃斯(Helen Molesworth)在深入探討黑山學院對1950年代末及60年代藝術的影響時,將注意力引向了阿薩瓦作品中形態的擬人化。她認為,阿薩瓦在黑山學院期間上了默西·坎寧安的舞蹈課,這有助於她「了解了人體的表達能力」。【22】 姚強(John Yau)曾將她的雕塑與女性的肢體相關聯,【23】它們容器狀的形態似乎隱約暗示著生命的誕生與延續。這些雕塑具態的形式,在攝影師、也是阿薩瓦的好朋友伊莫金·坎寧安(Imogen Cunningham)拍攝的精彩的照片中得到了凸顯,坎寧安拍下了藝術家阿薩瓦在自己家中的鏡頭,孩子們和她的作品圍繞在其身邊。與上文所述的那種刻意擺拍、毫無生氣的時尚攝影相比,這些照片展現出作品親密和感性的特點。這些特質讓人想到路易斯·布爾喬亞(Louise Bourgeois)1940年代晚期及50年代初期的「人物」(Personages),它們與阿薩瓦的金屬絲線形態一樣,與傳統的理想化的女性裸體的表現相比,更為基本、原初。【24】

人們還將之與安妮·阿爾伯斯和萊諾·托尼(Lenore Tawney)的編製作品聯系起來,認可並欣賞其創作過程對作品之意涵所做的貢獻,喚起了人們對諸如時間和連續性元素的思考。類似地,阿薩瓦透明的懸吊式金屬絲線作品,與伊娃·海瑟(Eva Hesse)的垂懸細線作品相比,具有同樣的物質性特征——海瑟被公認為最敢於挑戰其男性同行們更具攻擊性和英雄主義的創作姿態。

這樣的密切關聯數不勝數。可以說,如今人們對她作品的欣賞和理解沒有辜負巴克敏斯特·富勒對她才華的評價。同樣感人的,是阿薩瓦作為一位藝術家、教師、公民所樹立起來的榜樣。1990年,當被問及她對自己的藝術遺產有何期待時,她回應道:「調整、適應、從無到有的能力。」【25】

【腳註】

這篇文章最初發表於《魯斯·阿薩瓦》,展覽圖冊(紐約:卓納圖書出版,2018年)。

【1】R.·巴克敏斯特·富勒(R. Buckminster Fuller),寫給約翰·西蒙·古根海姆基金會的信,1971年9月30日,出自《魯斯·阿薩瓦文獻》(M1585),斯坦福大學圖書館特殊藏品及大學檔案部。

【2】富勒,有關魯斯·阿薩瓦的文字,1982年1月18日,出自《魯斯·阿薩瓦文獻》(M1585)。

【3】有關1971-1972年資助周期內頒發的獎項信息,來自於此網頁:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Guggenheim_Fellowships_awarded_in_1972。

【4】魯斯·阿薩瓦,出自凱蒂·西蒙(Katie Simon)的《與藝術家魯斯·阿薩瓦的對談》,收錄於《藝術周刊》(Artweek,1995年8月),第18頁。

【5】阿薩瓦,引語出自莎莉·B·伍德布里奇(Sally B. Woodbridge)的《魯斯·阿薩瓦的舊金山噴泉,聯合廣場凱悅酒店》,作品宣傳冊(舊金山,1973年),第5頁。

【6】姚強(John Yau),《魯斯·阿薩瓦:改變雕塑的定義》,收錄於《魯斯·阿薩瓦:物件與幽靈》,展覽圖冊(紐約:佳士得出版,2013年),第5頁。

【7】阿薩瓦,引語出自瑪麗·艾瑪·哈里斯(Mary Emma Harris)的《黑山學院》,收錄於《魯斯·阿薩瓦的雕塑:空氣中的廓形》,丹尼爾·康奈爾(Daniell Cornell)編輯,展覽圖冊(舊金山與伯克利:舊金山藝術學院與加州大學出版社出版,2006年),第45頁;以及舊金山藝術學院研討會的發言稿,1989年4月7日,出自《魯斯·阿薩瓦文獻》(M1585)。

【8】哈裏斯,《黑山學院》,第43頁。

【9】1963年,在舊金山藝術博物館舉辦約瑟夫·阿爾伯斯的回顧展之際,阿薩瓦發表了一次演講,有關她身為阿爾伯斯學生的經歷,引語出自她的演講筆記。出自《魯斯·阿薩瓦文獻》(M1585)。

【10】參看魯斯·阿薩瓦的《P3組合[東京]與魯斯·阿薩瓦的對談》,1989年,出自《魯斯·阿薩瓦文獻》(M1585)。

【11】參看尼古拉斯·福克斯·韋伯(Nicholas Fox Weber)的《魯斯·阿薩瓦和安妮與約瑟夫·阿爾伯斯:絕佳的靈魂伴侶》,收錄於《魯斯·阿薩瓦:物件與幽靈》,第32頁。

【12】阿薩瓦場說起,是她對繪畫的興趣促成了她金屬絲線雕塑的創作。此處的引語來自《日裔美國女性藝術家:纖維與金屬》,展覽手冊(華盛頓州奧林匹亞:常青州立大學常青藝廊,1984年)。

【13】阿薩瓦,藝術家陳述,1991年,出自《魯斯·阿薩瓦文獻》(M1585)。這是一份手稿,可能是已在某本圖冊中發表了的陳述。

【14】阿薩瓦,引語出自傑奎琳·霍弗(Jacqueline Hoefer)的《魯斯·阿薩瓦:創作的一生》,收錄於《魯斯·阿薩瓦的雕塑:空氣中的廓形》,第16頁。

【15】《明日的藝術家們》,發表於《時代》雜誌(1948年8月16日),第45頁。

【16】參看艾米麗·K·多曼·詹寧斯(Emily K. Doman Jennings)的《批判批評:露絲·阿薩瓦的早期創作反饋》,收錄於《魯斯·阿薩瓦的雕塑:空氣中的廓形》,第128-137頁。

【17】埃莉諾·C·蒙羅(Eleanor C. Munro),《杯子裏的世界,在球體中》,發表於《藝術新聞》(ARTnews,1956年4月),第26頁。

【18】多爾·阿什頓(Dore Ashton),《橄欖石畫廊、ACA和海勒(Heller)的展覽》,發表於《紐約時報》(1956年3月14日),第36頁。

【19】《東方酵母》,發表於《時代》雜誌(1955年1月10日),第54頁。

【20】艾迪·拉尼爾(Addie Lanier),與作者的對談,2017年6月。

【21】瑪蒂卡·薩溫(Martica Sawin),《魯斯·阿薩瓦》,發表於《藝術文摘》(Arts Digest,1954年12月15日),第22頁。

【22】海倫·莫爾斯沃斯(Helen Molesworth),《先行而後思:黑山學院1933-1957》,展覽圖冊,波士頓當代藝術博物館(康州紐黑文:耶魯大學出版社出版,2015年),第366頁。

【23】姚強,《魯斯·阿薩瓦:改變雕塑的定義》,第14頁。

【24】參考喬納森·萊布(Jonathan Laib)的《魯斯·阿薩瓦:物件與幽靈》,第25頁。

【25】阿薩瓦,引語出自《魯斯·阿薩瓦:藝術家兼教育家》,收錄於《力量與多樣性:日裔美國女性,1885到1990年,課堂學習指南》,第20頁,由美國國家日裔美國人歷史學會出版,隨加州奧克蘭博物館舉辦的同名展覽同期出版,1990年。出自《魯斯·阿薩瓦文獻》(M1585)。