November 21, 2018

How did this project come about?

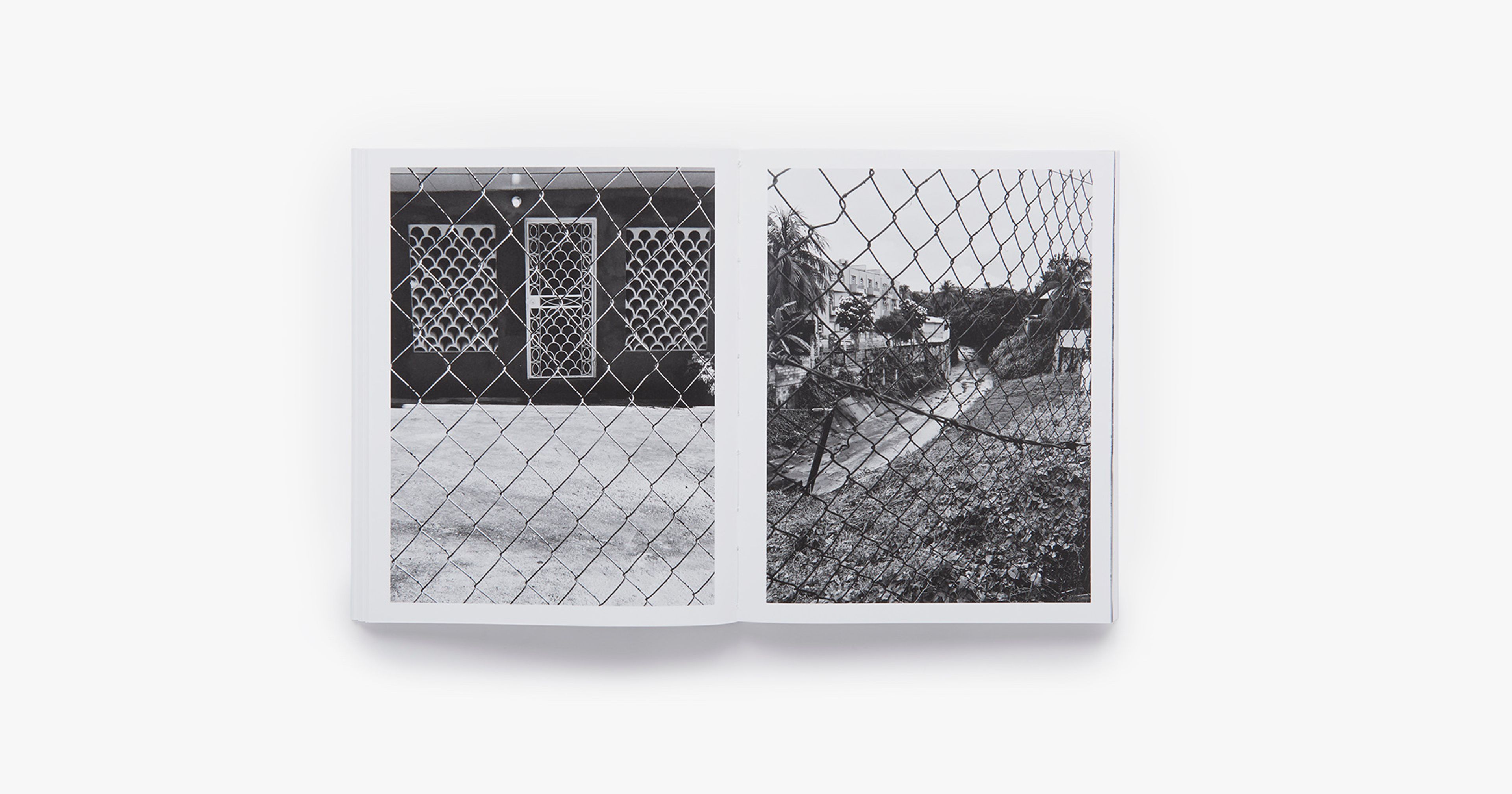

Well, I’ve known Chris for years, mostly just from being in Trinidad—the island in the southern Caribbean that I love, that I’ve written about, and where Chris lives and works. But the idea of having me write on this new project, that came from Lucas [Zwirner], here in New York. I went to see the Paradise Lost show last fall—the exhibition didn’t actually feature Chris’s photos, which comprise this book, but it did engage similar themes: he had brought actual chain-link fences into the gallery, along with stark black-and-white paintings. But I gathered that Chris’s larger vision for the project also involved compiling these images he’d been making with his iPhone, of fences and life in Trinidad, into a book. Lucas showed me the photos—these mysterious snapshots, beautifully composed. I thought: right, chain-link fencing—it’s everywhere in the Caribbean. I might have something to say here. We got in touch with Chris, and he loved the idea of me doing an essay, and we just went from there.

In your essay, you discuss meeting Chris Ofili a decade ago in Trinidad. Do you remember where or when you first encountered his paintings?

Yes, I certainly knew Chris as a person before I really knew his paintings. I knew his name and had seen images on the internet or wherever; I knew about the kerfuffle over his Virgin Mary. But meeting him and getting to know him in Trinidad was about other shared interests—in film and in books, in exploring the wild places and wild parties of the island.

But I do vividly recall encountering his paintings properly, for the first time. It was at his big retrospective at the New Museum in 2014. That show included work reaching back to his London years—those meticulous, layered pieces, porno cutouts and googly eyes and mothers’ tears and all, with which he made his name. All potent and impressive—and hilarious. But what really blew me away in that show was his newer work from Trinidad. There was one dimly lit room, in particular—you kind of had to squint to see; the canvases were painted in such dark indigos and blacks.

I remember writing him, that they were midnight in Trinidad, in the best way. Bougainvillea and creepers and all. Those pieces were magic—they captured something crucial about this tropical place where every day includes twelve hours of dark; where there’s something deeply noir about the culture; where stories abound about the midnight robbers and diablesses and blue devils that people the night.

Can you talk a little bit about what you wanted to frame or think through in writing about Ofili’s first photography project?

For me, it was really just about responding to the work—flipping through the photos, looking closely, seeing what emerged. And of course what leapt out straight away were the chain-link fences. Their ubiquity in Trinidad, which relates to a certain set of anxieties, particularly around "security" and protecting one’s person or property, in a young nation that can feel pretty Wild West—a place where the rule of law’s sketchy and where crime, lately, has been through the roof. Chris’s images speak to all that. But it was also clear to me, in how he approached these fences—how he took notice of the ways their patterns could be turned into decoration, how he caught, too, the beautiful diamond-shaped shadows they cast—that they weren’t just that. There’s another kind of cage, particular to Trinidad, that one feels guides this project, too—the birdcages in which men there keep trilling sparrows. These were evoked, a couple of years ago, by Chris’s grand tapestry The Caged Bird’s Song. Those cages—cages that evoke constraint, but also freedom and pleasure—keep showing up in the Paradise Lost project, too.

So that was the brew, as I absorbed this work, that was in my head. But I think as a scholar, my first instinct, in trying to figure out some sort of synthesis—some way to deepen context or furnish insight—is to turn to research: to actual materials, concrete history. Which in this case meant diving into the history of chain-link fencing. Into where this stuff—which was invented by a wool weaver in England, in the context of the Industrial Revolution—came from; into how it overspread the world; into the hows and whys of its ubiquity today as a way to bound off space. The hope, I suppose, was that diving into all that might shine some light on how and why Chris, in Trinidad, is encountering this material now—and what his images might say to us.

You have studied and written a lot about islands. What draws you to this particular subject matter, and are there recurring themes around this subject that you find in Ofili’s photos?

As a writer who went to school for geography, space and place are central to me. Questions around the means by which we turn space into place—location vested with meaning—are everything. And I think that islands, in general, are remarkable places in which to think through these questions. Partly because they’re at once "places apart," and places that are connected to everywhere, by the sea. But also because—especially in the context of the Caribbean—of all that’s been projected onto them, by western imaginations in particular: islands are utopias or prisons; they’re places we go to find ourselves, or lose ourselves, or be reborn. They have also long been conjured as paradises. Which is part of why when they turn out not to be paradise, but worldly and imperfect indeed (and crisscrossed, like Trinidad, by fences and anxieties of all kinds)—well, that’s when they get interesting.

What aspects of Trinidad’s modernity feel most foregrounded in Ofili’s "pocket photography"? Did anything surprise you while researching the history of chain-link fences?

In my essay, I quote a famous line from V. S. Naipaul, in which he describes Trinidad, where he grew up, as typified by a certain "flawed modernity." This cutting remark was typical Naipaul: he hated where he came from. But this sense of the island’s modernity—its stature as a place whose oil cash and ethnic mix and traffic-clogged roads feels modern—is typical Trinidad. Trinidad, in many ways, is unique in the Caribbean. Its economy isn’t tourism but industry. It has its own money, from oil and gas. And its culture is this vibrant mash-up of India and Africa and carnival and Shakespeare and steel drums. That culture and the mix of people in a New World nation, making it up as they go along; the music—all this helps it feel more modern than anywhere you can imagine. But there are so many ways, too, in which it can feel like a future to fear. A future where the planet’s heading—the traffic and the crime; the sense that everyone, living behind their metal fences, has something to dread. Those are some of the tensions attending Trinidad’s modernity. And they all come together, really, in a pretty neat little package: chain-link fences.

It was a pure bonus when I started to research fencing’s history to learn one particular detail. Norwich, England, where the fellow who invented chain-link fencing in the 1840s, Charles Barnard, lived, was for centuries a center for weaving wool and making textiles. Barnard’s idea was to retrofit a loom, to handle material stouter than wool—the idea for braiding steel into fencing came, literally, from a machine for making cloth. Which was rather perfect to find out while writing about Chris, a painter who’s been interested in metal and cloth alike. And who’s also worked, in the case of the textile he produced with the Dovecot Tapestry Studio, with a similar kind of alchemy—in The Caged Bird’s Song, turning watercolors into yarn. But there was something there, too, that resonates: the ways in which one material, or process, can become another.

Sometimes, digging into history does that. It connects to the present, and the work, in these serendipitous ways that maybe aren’t so serendipitous at all: one feels the artist’s eye making connections that have been there all along. Connections that are there, in the images, to be discovered—or mused upon anyway. Engaging with Chris’s work in this essay, in that spirit, was fantastic fun. And I think the aim, in combining the words and images into a book, was to create a kind of conversation that people find interesting. I hope they do!

Image: Photo by Kyle Knodell