“To quote George Orwell: every artist ‘has a ‘message’...”

December 20, 2019

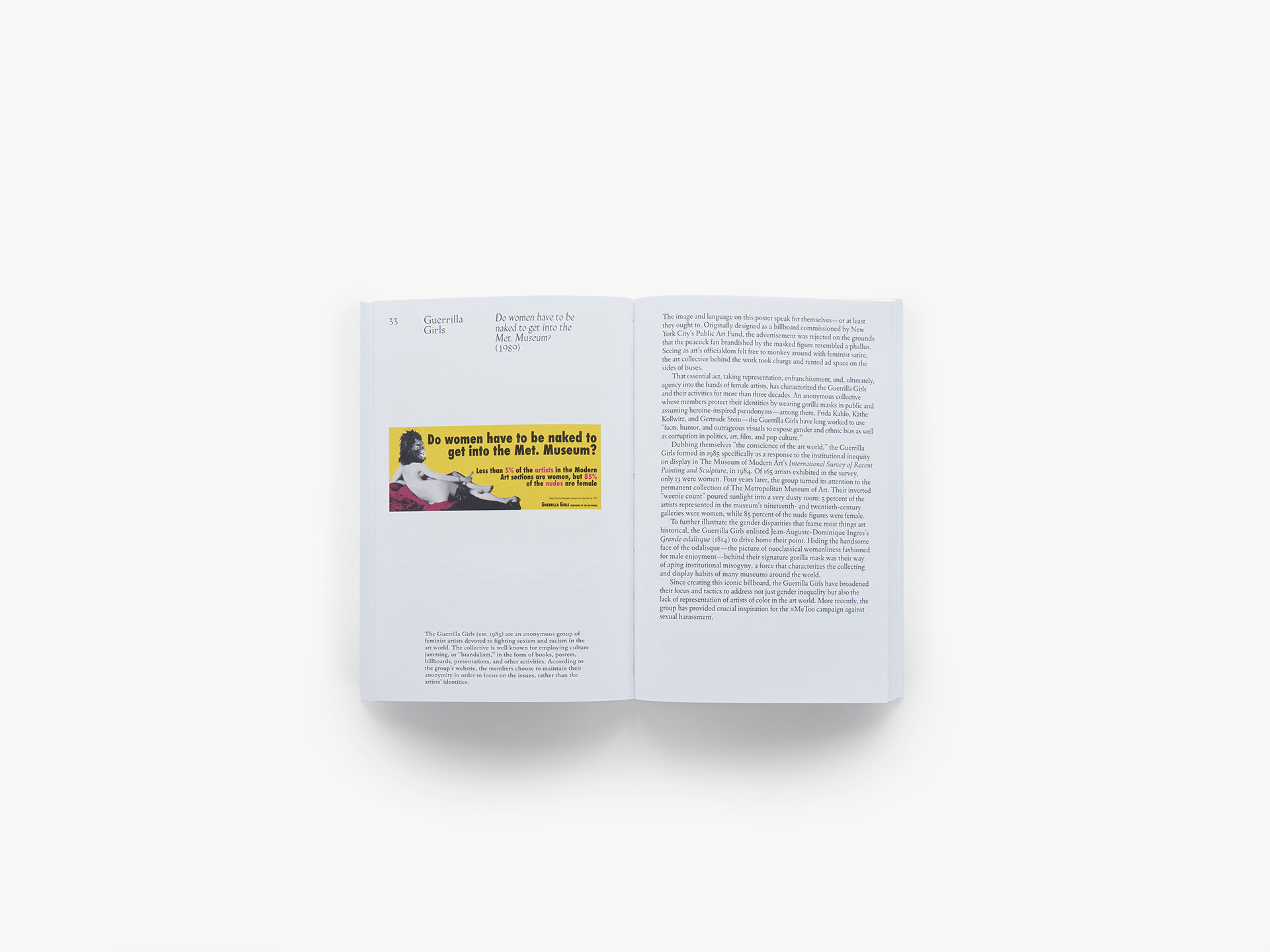

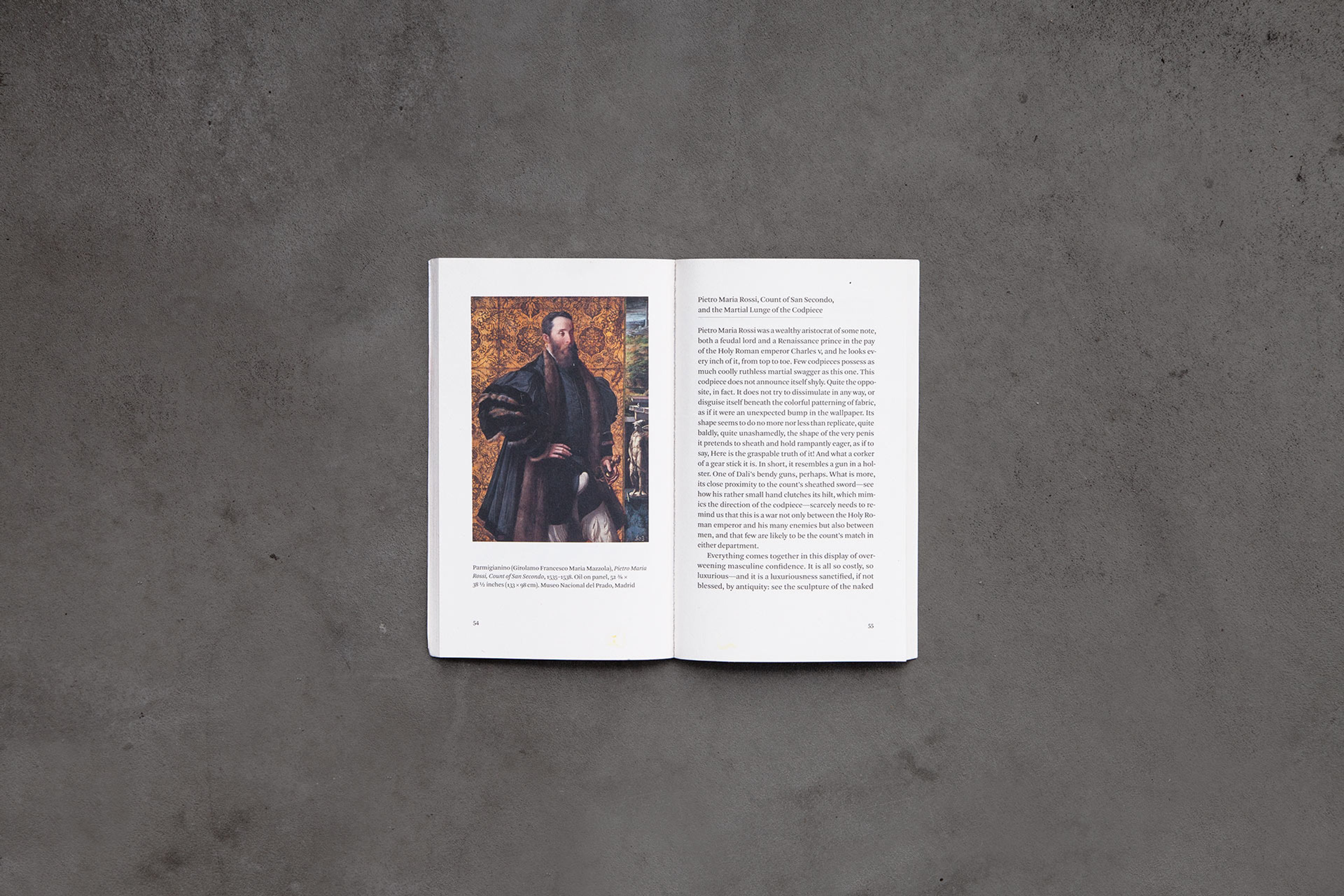

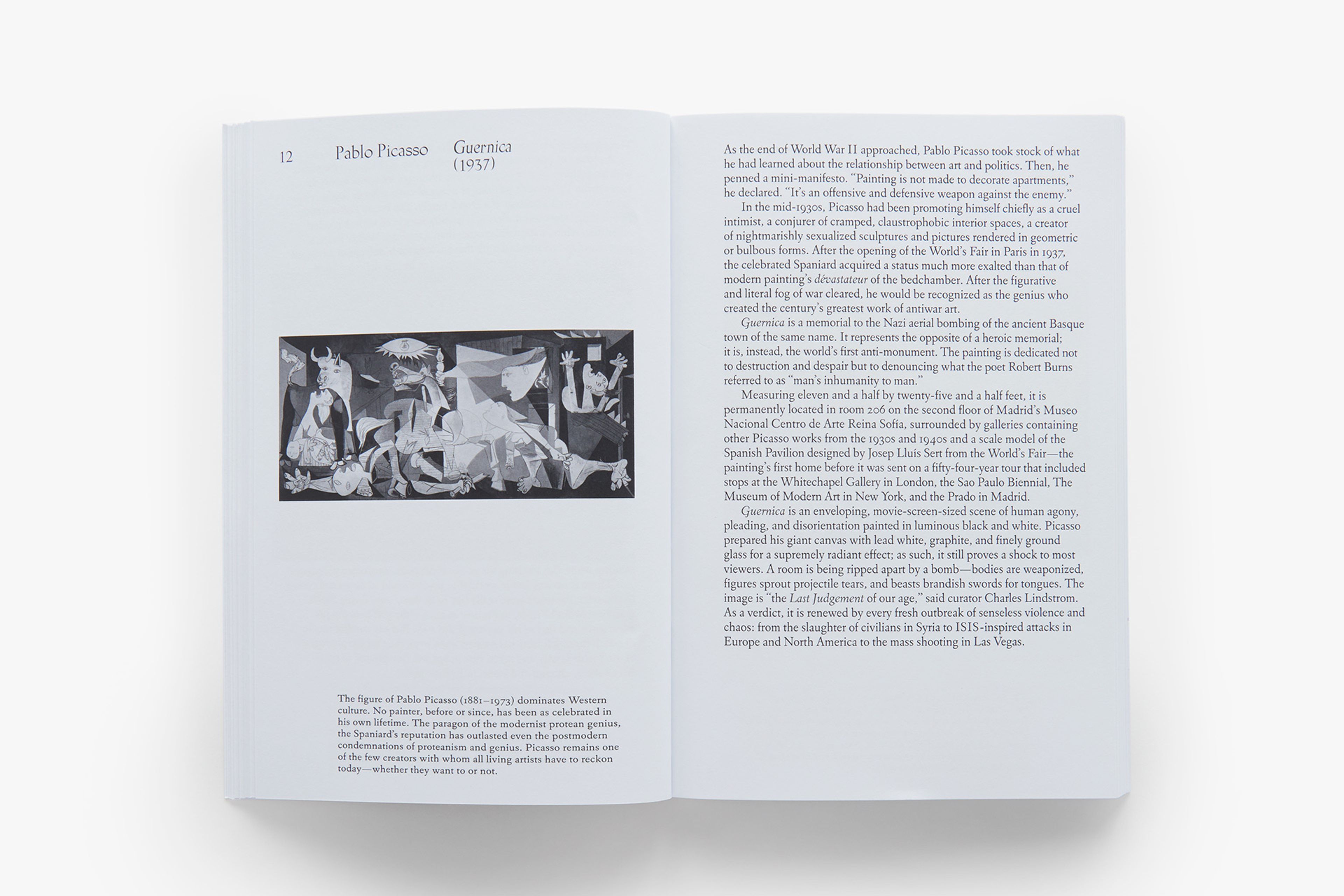

In Social Forms: A Short History of Political Art, renowned critic, curator, and writer Christian Viveros-Fauné has picked fifty representative artworks—from Francisco de Goya’s The Disasters of War (1810–1820) to David Hammons’s In the Hood (1993)—that give voice to some of modern art’s strongest calls to political action. In accessible and witty entries on each piece, Viveros-Fauné paints a picture of the context in which each work was created, the artist’s background, and the historical impact of each contribution. At times artists create projects that subvert existing power structures; at other moments they make artwork so powerful it challenges the very fabric of society. Whether it describes Picasso’s Guernica and its place at the 1937 World’s Fair, or Jenny Holzer’s Truisms (1977–1979), which still stop us in our tracks, this book tells the story behind some of the most important and unexpected encounters between artworks and the real worlds they engage with.

Christian, as a full-time observer and curator of, teacher, and writer on art, what gets you out of bed in the morning?

Besides deadlines and Dwight Garner’s book column, the idea that I might see, read, or hear, never mind write, something clever, surprising, or illuminating during the day. Of the three possibilities, I find surprise to be consistently in shortest supply. Beauty, like smarts of all kinds, invites mimicry, which is how we get variations on a theme, tropes, genres, art forms even. Surprise, though, contains a special quality. The best art, I’ve always thought, aspires to the quality of a revelation—eyebrow arching, O-mouthed newness, which is the definition of surprise. Surprise is the double espresso shot in the soy venti latte of life.

What’s on your bookshelf, old and new?

Catalogues, art history, books on politics, novels, collections of essays, these last being an excellent antidote to writer’s block. The newest additions to my bookshelf are well-crafted takes on cultural and epistemological crises similar to the one we’re enduring at present. There’s Edna O’Brien’s Little Red Chairs, a novel about an Emma Bovary character having an affair with a Radovan Karadžić type; Dorian Lynskey’s The Ministry of Truth: The Biography of George Orwell’s “1984”; Masha Gessen’s The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia; Kwame Anthony Appiah’s The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity; Elaine Scarry’s On Beauty and Being Just; and Tzvetan Todorov’s Goya: In the Shadow of the Enlightenment. I’m reading the Todorov in Spanish because my French is lousy. In fact, I’ve been reading a lot about Goya, since I’m trying to get a book about his political art off the ground. Goya wasn’t merely influenced by the spirit of the Enlightenment, he was one of its principal figures. He expressed the idea that reason itself can lead to barbarism more than a hundred years before Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer applied their noggins to it in The Dialectic of Enlightenment.

What do you procrastinate with?

The list is long and includes emails, newspapers in Spanish and English, restaurant reviews on Wednesdays, and two football publications in the morning. When I say football, I mean the sport Americans insist on calling “soccer.” Like Donald Trump, Americans like things they can take credit for having somehow “invented,” and world football is not one of those things. Fundamentally, Americans hate football because it’s cosmopolitan and other nations win at it. I love it for both of those reasons, but also because it is, hands down, the most democratic game ever invented. It’s designed to reward skill and smarts over brawn and athleticism, to let David thrash Goliath—in footballing terms, Lionel Messi gets to regularly thump fellows built like LeBron James. Also, you don’t need helmets, rackets, pads, hoops on metal poles, or week-long ski passes to delight in it. A round sphere will do, any kickable object, really. In school in Chile, we played with the class eraser.

What was the tipping point for Social Forms?

I first came up with the idea for the title as a peg for an exhibition that never happened, or, I should say, hasn’t happened yet. Political art, as I say in the book, is the hardest art to make, or at least the hardest to get right. Like crime and scripture, great political art involves both premeditation and opportunity, inspiration, and incarnation. As we know, not every political crisis gets the art it deserves, but some crises do. When this happens, pioneering works of art, along with the events they refer to, are rendered beyond memorable—they are fully memorialized, as surely as if they were cast in metal and stone, like the Washington Monument or London’s Cenotaph. In my view, such works also mobilize revelatory ideas throughout history in a way that denotative language, especially political language, simply can’t. Part of what led me to want to write the book was that I didn’t know of another volume that addressed the history of political art from the advent of modernity to the present. Another motivation was, as you might imagine, the state of the world today. This is obviously not a how-to book on political art, but it might serve as a short history of how art was made during times of social and political upheaval.

There’s a great range of works here, from nineteenth-century paintings by Goya, Delacroix, and Turner to Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1920), Cildo Meireles’s Coca-Cola Project (1970), Guerilla Girls (1989), Shirin Neshat’s Women of Allah (1993–1997), and Charlie Hebdo (2015), to name a few. How would you say the character of political art has evolved—from presenting specific events, for example, to speculation or undermining an atmosphere through conceptual or other means?

The best political artworks don’t just meet the challenges of their time head on, they propose advances on those ideas in ways we are still coming to terms with. Of the works you mention, Meireles’s piece, in particular, illustrates the notion that art can, given certain historical challenges, transform both the medium and the message. Like many artistic “inventions,” Meireles’s use of a bottle-deposit system to spread anti-government messages is ingenious: it sat under the nose of generations of international artists before he saw fit to harness it in 1970s Brazil. The fact that he did so using Coca-Cola bottles, of all things, mobilized systems of value and signification in ways that resemble the Guerrilla Girls’ use of bus advertisements in 1989, Turner’s abolitionist canvas in 1840 (he painted Slave Ship partly in the hopes that it would catch the eye of Prince Albert at the British Anti-Slavery Convention of the same year), and Goya’s use of prints starting in 1810. Art’s multiple mediums have evolved historically, along with the understanding of what constitutes art, but the idea that these various mediums can be employed to channel what the poet Yves Bonnefoy called figural thought remains fairly constant. Image is thought. There are few greater examples of this than the full title of Meireles’s Coca-Cola Project: the first part is Insertions into Ideological Circuits. I could have simply named the book that and been done with it.

Having looked at all these examples, would you say is art a reliable narrator? What is your hope for its collective voice? To paraphrase Bonnefoy again, great art is made of symbols that catch us unawares, of impressions that inflame the entire body. Art is, therefore, not a reliable narrator in the sense of accuracy and impartiality, nor is it supposed to be. Impartiality wasn’t Hans Holbein’s intention when he gifted the world a mortuary slab version of our savior in The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1521), and it isn’t now, when a filmmaker like Richard Mosse uses a battlefield-surveillance camera to capture the global migration crisis. To quote George Orwell: every artist “has a ‘message,’ whether he admits it or not,” and all art is persuasion or—as he puts it without intending the term pejoratively—propaganda. We’ve spent some decades where art has largely turned its back on the world and its messy problems, especially in the West. I welcome the idea that artists have turned the page and are once again applying their skills to addressing the challenges of their time.

Were there any notable works you decided not to include for one reason or another?

There were. I started with a list of one hundred works, but the editors pared that back to just fifty essays on fifty images. I would have loved to include Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19) and more contemporary artworks by artists like Agnes Denes, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Arthur Jafa, Mel Chin, and Teresa Margolles, but there wasn’t enough room. There was also the case of a legendary artist who appeared to want to soak the project financially. No need to name names there.

What kind of art is your refuge when (or if) you don’t feel like thinking about politics?

I have very catholic, ecumenical taste in art. Having said that, I really do believe all art is political. Still, I can enjoy work that is not overtly political with the same relish as I can art that is declaratively so. Giorgio Morandi painted his tabletops and bottles through two, count them, two world wars, same as the futurist Giacomo Balla. I would agree with most reasonable folks that Morandi’s was the greater contribution to world art.

Do you think expectations of art for pleasure or for politics are at odds? Or, where’s the fun in politically engaged art nowadays?

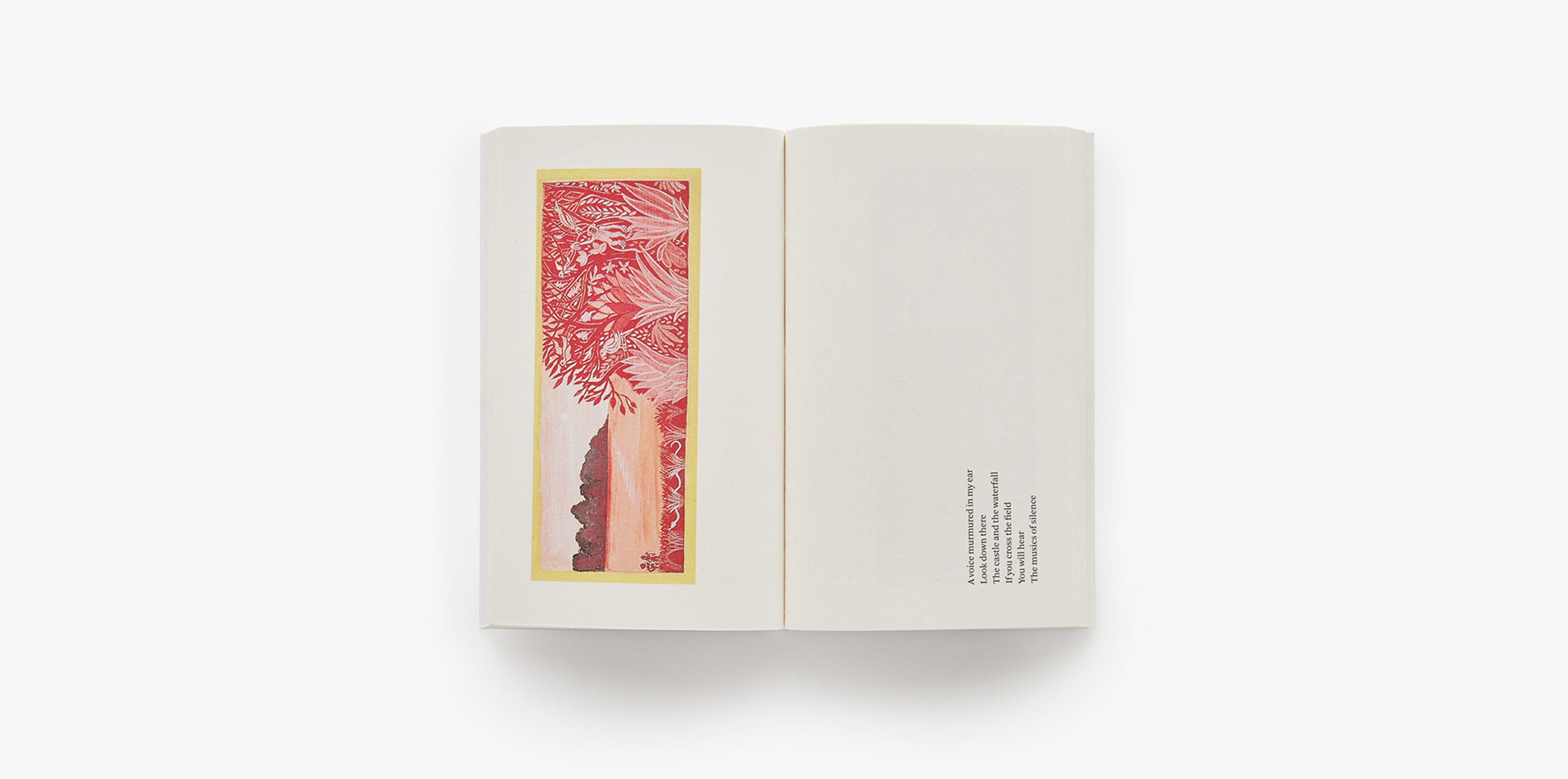

There’s pleasure in beauty, and there’s plenty of beauty available in politically minded art of both classic and recent vintage. Kara Walker’s cut-paper silhouette compositions are just gorgeous, both in their elegance and economy; so much so that they resemble scientific or mathematical proofs, which recalls ways in which the term beauty is still used by astrophysicists, neurobiologists, et al. Symmetry, simplicity, formal elegance, those are requirements for most successful works of art, no less so for works of political inspiration. It may, in fact, be that political artworks have an even greater responsibility to do right, formally and otherwise, by the urgency of certain claims or ideas (and the people they represent or impact). Consider Rick Lowe’s Project Row Houses (1994–ongoing). I say in the book that his evolving art-driven community in Houston is not only the world’s greatest work of social sculpture, it is the Demoiselles d’Avignon of this century. To quote Elaine Scarry paraphrasing Iris Murdoch: beauty prepares us for justice. As for fun, I confess to having burst out laughing when I first saw Walker’s work. That is fundamentally the same reaction I’ve had to hearing brilliantly written and performed bits by Richard Pryor or Dave Chappelle. I couldn´t believe she’d gone there, in that way!

Recently we’ve seen some artists making political statements outside their artistic practice—this year’s Turner Prize being a case in point. Is there a shortlist of artists making political statements outside of their art you find notable?

There’s a political turn in art at present, no doubt about it, and a turn to philanthropy, even to activist philanthropy among artists. There’s Mark Bradford’s Art + Practice in Los Angeles, Titus Kaphar’s NXTHVN in New Haven, Nan Goldin’s opioid crisis advocacy group P.A.I.N., and much more. Maybe I should be pitching Social Forms part II?

You once likened art ecologies to coral reefs, as fragile things that are highly susceptible to change. How about the art world’s own politics in relation to the wider situation? What have you observed about the effects of the current atmosphere on this still-specific niche?

The macro affects the micro, so of course the art world’s own politics will have to change, or continue to change, that is. There’s talk of censoring certain kinds of art and problems with unworthy patrons sitting on museum boards today, but that’s just part of a much larger discussion that involves a macrocultural transvaluation of values, to take a phrase from Nietzsche, that puts into serious question whether citizens of liberal democracies want to continue being just that, citizens of liberal democracies. We’re at an inflection point civilizationally today where the concerns of our little community can, at times, have an outsize impact, now or years from now. Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) was an immediate hit, Goya’s Disasters of War (1810–20), not so much, since those etchings weren’t published until 1863, thirty-five years after the artist’s death. Yet those images remain central not just to how we imagine the horrors of war but to the idea of the breakdown of civilization itself, to “man’s inhumanity to man,” to quote Robert Burns. That’s news that stays news but also a prime example of how an artist can pitch his or her ambition to capture what you call the wider situation.

Five years after the last work you explored in the book (Theaster Gates’s Stony Island Arts Bank, 2015–ongoing), where are we now? Are there particular threads or developing themes you are noticing and excited about?

I’m excited by art’s wider engagement with the world and horrified by an expansion of cheap outrage, censorship, and self-censorship. Fairness, like beauty, is a clarion call, but also a destination that’s arrived at through dialogue. Everyone gets to have their say, otherwise the system breaks down and both art’s peaks and valleys are devalued.

And finally! If you found yourself in a quiz, answering questions about all of the fifty works covered in Social Forms, which is the one you know most intimately, or remember most vividly?

Probably The Disasters of War, despite the fact that the series consists of eighty-two prints. Didn’t I say I was on a Goya kick?

Images: Social Forms: A Short History of Political Art. Photos by Kyle Knodell