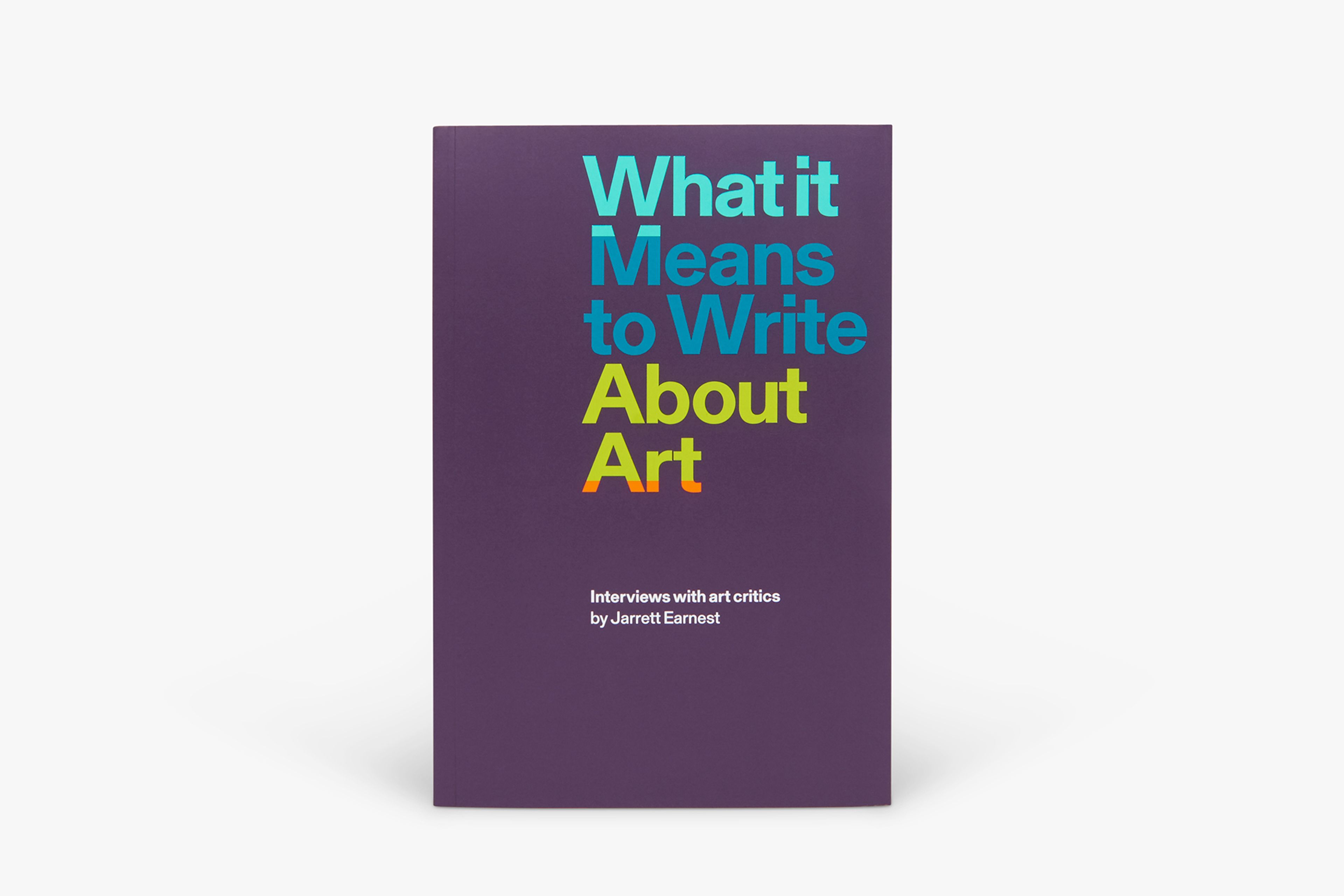

Read this week's David Zwirner Books excerpt

April 3, 2020

Equal parts oral history and analysis of craft, What It Means to Write About Art offers an unprecedented overview of American art writing. These thirty in-depth conversations chart the role of the critic as it has evolved from the 1960s to today, providing an invaluable resource for aspiring artists and writers alike. John Ashbery recalls finding Rimbaud’s poetry through his first gay crush at sixteen; Rosalind Krauss remembers stealing the design of October from Massimo Vignelli; Paul Chaat Smith details his early days with Jimmy Durham in the American Indian Movement; Dave Hickey talks about writing country songs with Waylon Jennings; Michele Wallace relives her late-night and early-morning interviews with James Baldwin; Lucy Lippard describes confronting Clement Greenberg at a lecture; Eileen Myles asserts her belief that her negative review incited the Women’s Action Coalition; and Fred Moten recounts falling in love with Renoir while at Harvard. Jarrett Earnest’s wide-ranging conversations with critics, historians, journalists, novelists, poets, and theorists—each of whom approach the subject from unique positions—illustrate different ways of writing, thinking, and looking at art.

Image: Johannes Vermeer, Young Woman with a Pearl Necklace, 1664. Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin

Holland Cotter

I want to start by talking about your early life and your relationship with poetry. How did that connection with language begin?

It started at home. I grew up near Concord, Massachusetts, outside of Boston. My parents were a very young postwar couple. My dad had just started medical school when I was born, so there was no money to speak of, but they were resourceful. They were book readers, museum goers, and they loved music, especially jazz. While my dad was in school at night, my mother would read my younger sister and me poetry at the dinner table—just a routine thing that she did. Her taste in poetry included Emily Dickinson, which she thought would appeal to us because her poems were short and had references to nature, but also the language is so startling—it wakes you up and makes you listen. I got a lot of Dickinson early on.

* * *

Darby English

What would you point to as an early important aesthetic experience? When I was a child, we went to The Cleveland Museum of Art. My favorite experiences were of strolling through those galleries with parents who enjoyed this very much. They weren’t necessarily always equipped to provide detailed information about the art we were looking at, but they were only too happy to indulge their only child in this way. At a certain point, it must have been clear that I was the person who needed this experience the most, but I was never made to feel as though my interest was a burden to them. I don’t recall having a lot to say about it—ever since I could talk I have had speech impediments, and this predisposed me to keep words to myself—but I loved looking, in a deep and abiding way. I guess I looked really hard; I certainly wanted to look often. My first real loves were Dutch landscape paintings by Ruisdael and Van Goyen, which I revisited almost on a pilgrimage basis. I was mainly looking at paintings; it took me the longest time to learn how to see sculpture of any kind. The Portrait of Tieleman Roosterman [1634], by Frans Hals—I saw it again recently, and it’s still to me as completely fixating as ever. Looking back, I feel that a painting like that appeared to me as something like mitigated truth.

* * *

Siri Hustvedt

There is an essay in A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women where you offhandedly say that your mother used to call you “too sensi-tive for this world”—I’m wondering about that and how it relates to your early aesthetic experiences. That particular essay, “Becoming Others,” is about my mirror-touch synesthesia, a form of synesthesia that wasn’t named until 2005, although obviously people have been walking around with it forever. It’s a physiological phenomenon: if I see another person slapped on the cheek, I have a sensation in my own cheek. I also have strong physical responses to colors—once while looking at a shade of turquoise in Iceland, I had a revolting crawling sensation all over my body. Everyone responds to color, but my mirror-touch sensations probably exaggerate the response. At the same time, I can’t jump out of myself and check what it is like for you. When I was growing up, it never occurred to me that other people didn’t feel what they saw.